The Middle of the Sentence

Basketball as metaphor and more.

By Alan Filreis

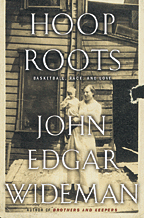

HOOP ROOTS: Basketball, Race, and Love

By John Edgar Wideman C’63 Hon’86.

Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. 242 pp., $24.00.

Order this book

John Wideman has been writing about his own and others’ mortality for a long time, but nowhere more movingly than in this new book, a work that is ostensibly about basketball. Hoop Roots is Wideman’s own pre-elegy.

In this beautifully disarranged portfolio of narratives about his various recent returns to the playground as an “old head” and a “usta-be,” he writes about being old in advance of really being old. On the court he has seen himself die already; in the new book he moves in a simultaneous or synchronic time, non-narratively back in time, to moments when he was already old and the young leggy players, the “newest, fastest ones,” had already superceded him. These youngbloods “didn’t know you from before,” and they “grumbl[ed] when you couldn’t keep up with the way they played the game.” Wideman is dying out of his basketball life before he dies out of life entire—long before, we can hope. It gives him a social preview of the new era. Age is the hoop caste system, but hoop age is radically relative, pushing the end hard toward one end of the scale, “old” in hoop coming well before old arrives in life’s other arenas. Thus hoop is a social test of our capacity for reinvention and improvisation. The politics of Hoop Roots is a “body politics,” an intramural struggle waged on courts of play, in “the no-man’s land of innovation,” animated by the young legs and the “the rush of their skills” and made urgent by the respect the young selectively feel for their heady elders. It is a contest that is, alas, no contest, for “today’s today” and “leg ball” (“[s]ignifying you don’t need a brain to play it”), which is an in-your-face form of forgetting, seems to win over remembering. The emotional message of this book is that remembering has always been the key to learning communally from past tragic mistakes.

In this mortal contest Wideman takes a position. By no means does he condemn the young ones (this is not a simple book). He aches for a passionate synthesis. In the struggle between, on one hand, no-brain leg ball and, on the other, the game he must now play (“taping up ankles, bracing knees, binding hamstrings, Ace bandages, spandex, Ben Gay, Advil, eye-glasses secured by Croakies”), language itself is on the side of the usta-be. Wise about this, Wideman accepts a broken writing. He creates a language more lovely than all the most lyric complete sentences he has written about basketball in earlier books. Returning now to the courts of his Homewood childhood, or lured onto a Greenwich Village playground during his courtship (as it were) of a new lover, Wideman finds himself “back in the middle of a sentence that hasn’t ended.”

In the time scheme of Hoop Roots the fragment is the truly human form. Once upon a time words had done the job. They had wholly worked to describe. But no longer, as the old head knows. Now language fills physical absences, stands in for the lack; from now on Wideman will write, in a sense, because he cannot play hoop. So the writing must be disrupted, unfinished, digressive, resisting endings, precisely like the disjunctive parts of this book. And since the book, as Wideman tells us, is ultimately about pleasure, we understand how pleasure comes more from digression than straight-ahead direction, more from words that don’t precisely mean than from sentences that disclose the world clearly. Hoop Roots gives us a compelling theory of words, how they must work after the body and the community are analogously ravaged. Whereas once we felt words located the things they denote, connected solidly to the rock (hoop’s slippery nickname for the ball), and whereas good words were satisfactions in themselves, now the present tense must somehow point to a time that is not just now. The present must be in the “middle of a sentence that hasn’t ended.” This is an experimental notion of time, what we might call a “middle time.” In Wideman’s new writing it is often closer in spirit and syntax to Gertrude Stein than to many another of his narrative and thematic predecessors. The healing response to the painfully gone past is not the immaturity of a simple present tense, where things stand plainly for themselves, where language tells you what things are. Rather, it is an improvised no-one-knows-where-it’s-going immediacy, something made in the playing and while the writing is being written.

All this makes for superb improvisation. We see the rush of Wideman’s skills in a book that has been written to lament the diminution of skills. When Hoop Roots is written in the present tense it is as complex and mature a version of writerly presence as I have read. “[H]oop is doing it,” he writes. “Participating in the action. Being there.” And: “We are doing this together.” “[B]ut the action is always gone.” “Stories place you in the presence of something perhaps experienced before, but since not named, in a sense unrecognized, though mysteriously tangible like the painful throbbing an amputated limb leaves behind in the space it once occupied.” These phrasings are about basketball, but they are also about the writing we are reading. In general they make a practice of writing that staves off dying, that restores presence in the face of tragic absence. Such an approach to language is also of course about improvisational African-American culture, the unreproducibility of modern jazz, a kind of expressiveness in which, as Wideman puts it, “[t]he present tense presides.” You play once and it is just that once an articulate fragment, for then it can never quite be repeated or attached to the whole. It is, as William Carlos Williams M’06 Hon’52 put it in a relevant poem about modern culture, a “pure product of America go[ne] crazy.” A good kind of crazy, although it inspires some fear from those who like stability. As basketball is a folk culture’s “determination to generate its own terms,” so is this writing once Wideman discovers the pure pleasure in it. Just when and where the world is “on your case to shape up, line up, shut up,” he wants pleasure, “the freeing, outlaw pleasure of play in a society,” to help resist and ultimately reshape that world. Thus the unshapely book and the writing, sentence by sentence, that refuses to shape up into a body. Implicit is a formal or sculptural principle. If the surrealist sculptor Alberto Giacometti was explicitly an aesthetic model in Two Cities, Wideman’s brilliant novel of 1998—there we read a series of letters written to Giacometti by one of the main characters—in Hoop Roots Wideman is even more committed to the idea of writing that “reliably supplies breaks” rather than creates wholes. “Fragments of performance suggestive of a forever unfinished whole, the perfect whole tantalizingly close to now and also forever receding.”

Wideman has discovered the connection between the kind of language into which he has matured and the game that in his tragedy-filled life gave rise to his antipathy for total explanations of social ills and for commodifications of black culture. Having made this connection, he can write of basketball in a way that is one model for a self-governing society, the radical republic of hoop. “The game’s pure because it’s a product of the players’ will and imagination,” a grammar invented there and then, a collaborative one-time-only art. In the modal republic of hoop the fast legs and old heads improvisationally create, adapt, and enforce the rules. “[P]layground hoop like all cultural practices at the margins engages in a constant struggle to reinvent itself.” Hoop requires, he says, no outside enforcement—“no referee, coach, clock, scoreboard, rule book. Players call fouls, keep score, mediate disputes, police out-of-bounds, decide case by case.” It is a model for true home rule, dependent upon the contest between no-brain and the brainy thoughtfulness that deeply knows the relation between language, culture, memory, and the mortality that (soon) awaits even today’s young legs. For Wideman this bespeaks the richness rather than the bleakness of postindustrial urban fragmentation if it can be depicted in a style more like Giacometti’s non-realist distortions and discontinuities and less like the do-good realism of social documentary. Hoop offers a non-narrative and undepictable free space in the middle of all this. “If urban blight indeed a movable famine,” Wideman writes in the book’s finest fragment, “playground ball the city’s movable feast.”

The writing is a significant advance upon basketball as thematic background in books like Philadelphia Fire (1990) and Brothers and Keepers (1984). Hoop there moved plots forward; served as stagings of urban dissent; made the politically necessary although obvious point that African American youth would narrate its own triumphs as a warrior’s alternative to the tradition of American stories; and of course wooed readers and critics with stunning depictive prose.

It is in the remarkable Two Cities that the “warrior spirit” of hoop began to compromise the future. There Wideman began to understand the anti-aesthetic of discontinuity as the alternative way of explaining how hoop could encourage rather than destroy love and community. In that novel the view that “All you need’s that warrior spirit to keep the old arms and legs moving” is called into question when the young woman who will save Robert Jones’s soul comes to watch him play playground hoop with much younger and more dangerous men and leaves him when the “dumb knucklehead macho shit” nearly leads to his shooting. She who has lost sons to gang violence “can’t love another dead man” and walks away from their love. The conventional gorgeousness of Wideman’s prose descriptions of basketball being played, such as this—

In his rainbow headband and giant baggy shorts ballooning past his knees like purple wings, he’s a butterfly pinned to the blue sky, a perfect snapshot she’ll remember of a man flying like a bird who just might hang in the air forever, and does each time she brings the day into her mind, even though the next thing he does is tomahawk the ball down through the chainlink net, landing where it lands with his legs spread wide, hovering over the ball like it’s an egg he laid, before he plucks it up and sets it gently as an egg on the endline, grinning Too late, too late like the gingerbread man at the other players

—is itself called into doubt as a sufficient kind of writing. The woman who teaches Robert how to love a blighted community, and the old, broken World War II veteran and amateur modernist photographer (Mr. Mallory, Giacometti’s correspondent), together unwrite hoop as the award-winning John Edgar Wideman had always written it before. They teach him to depict the urban scene in a way that “invite[s] a viewer to stroll around” it, “to see [things] from various angles, see the image I offer as many images, one among countless ways of seeing, so the more they look, the more there is to see.” The more we look at Two Cities and Hoop Roots, the more there is to see. It is this pleasurable “density of appearances,” a hoop cubism with radical social import, refusing any “single, special, secret view” in favor of many views simultaneously, that takes Wideman as a writer directly from the triumph of love he published in 1998 to the true social and aesthetic wisdom of Hoop Roots in 2001.

One event that came between Two Cities and Hoop Roots was Wideman’s visit to the Kelly Writers House in April 2000, a celebratory return to the scene of his first anxious foray into white academe and his glories on the court as an All-Ivy star of Penn’s basketball team. In several days of intense discussion with students, faculty, staff, West Philadelphia neighbors, old friends and colleagues, audiences that included coaches and players of Penn’s current team, we caught glimpses of what hoop was coming to mean for this writer entering late-middle-age experimentally. During a discussion I helped lead (and which was excerpted here in the July/August 2000 issue), I asked Wideman to elaborate on a story he had told my students the previous day. As a Penn freshman, one of a few black students on campus, homesick for Homewood, he had very nearly left the University after just six weeks on campus. What had made him stay? Hoop had. He explained:

Basketball was my safety zone. It was a sanctuary. I had no doubt I was wanted there, that I had a place there … The basketball court offers a kind of democracy … The rules are quite simple, and everyone knows them. If you don’t like them, you don’t have to go there. In sports, there’s a kind of openness about things and [yet] a really hard bottom line: If you hit the jumper, you can take the jumper … And some of the best teaching goes on in athletic programs, because you have such a willing constituency and it’s to some degree voluntary. The same way, in my creative writing classes, people come to me because I’m a writer. They believe I offer something they want, and if you can’t teach in those circumstances you’re pretty hopeless … On the hoops court, most of the time, what you did counted—not … what you wore before you stepped onto the court, not where you could go afterwards … You entered the Palestra and the court became a sort of magic square. You go out onto it, and you could create your own world.

This intrepid self-construction—the idea that we can help create our own world in writing as in hoop—leads to the brilliant social thesis of Hoop Roots. It’s this: “The game’s as portable as a belief.” The butterfly pinned to the sky is pretty, but it was dead and undynamic the moment it hit the page. Wise love could not come from it. Nor could self-creation. Hoop teaches Wideman to write his way back—although it is always moving—to the troubled, unsolid ground.

Dr. Alan Filreis is the Class of 1942 Professor of English and faculty director of the Kelly Writers House.

BRIEFLY NOTED

A selection of recent books by alumni and faculty, or otherwise of interest to the University community. Descriptions are compiled from information supplied by the authors and publishers.

DRAWING ON THE PAST: An Archaeologist’s Sketchbook

By Naomi F. Miller, Staff.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2002. 85 pp., $19.95. Order this book

In this book Naomi F. Miller takes the archaeological autobiography to a new dimension by pairing her drawings and paintings—inspired by over 30 years of fieldwork—with conversational prose narrative. The sketchbook places the reader in the center of fieldwork action at several major archaeological sites in Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Turkmenistan [“The Stamp Seal Mystery,” November/December]. We learn about many aspects of life on the dig: science and scholarship; digging and analyzing; local landscapes and local politics; shopping and cooking; eating and sleeping. Miller is a senior research scientist at the Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology in the University Museum.

JUST LET THE KIDS PLAY: How to Stop Other Adults from Ruining Your Child’s Fun and Success in Youth Sports

By Bob Bigelow C’75, Tom Moroney, and Linda Hall.

Deerfield Beach, Florida: Health Communication Inc., 2001. 333 pp., $12.95. Order this book

Today’s parents invest a great deal of time, money, and miles on the odometer to give their children access to sports experiences. It may surprise them to learn that many young athletes are being hindered, if not hurt, by participating in organized youth sports. Just Let the Kids Play offers a rare look inside the organized system of sports, confronting the sources of the trouble exploding on the sidelines everywhere—from fights among the adults to large numbers of children who quit sports at a young age. Focusing on the five most popular youth sports, the authors outline ways to set up teams that foster fair play, skill development, and social interaction, while also offering advice on how adults can keep themselves and others in check. Bob Bigelow, a former Quaker basketball player, played four years in the NBA and is now a part-time NBA scout and nationwide speaker. [See “Bob Bigelow’s Full Court Press.” ]

MUSICAL MEANING: Toward a Critical History

By Lawrence Kramer C’68.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 344pp., $22.50.

Order this book

How, why, and where is music heard? How can we integrate the study of music with social and cultural issues? Focusing on the Classical repertoire from Beethoven to Shostakovich and also discussing jazz, popular music, and film and television music, Musical Meaning explores these questions. Fusing a broad knowledge of recent cultural and critical theory with music literature, this book uncovers the historical importance of asking about meaning in the lived experience of musical works, styles, and performances. Lawrence Kramer, professor of English and music at Fordham University and co-editor of 19th-Century Music, has previously written six books, including After the Lovedeath: Sexual Violence and the Making of Culture.

CORPORATE PUNKS AMUCK

The Accountants (including Michael Shields WG’94).

Mix Works, 2001. $16.99. Order this cd

By day Michael Shields is CFO of Kenmark Optical, Inc. in Louisville. By night he can be found “rockin’ the corporate world” with his music as rhythm and acoustic guitarist for his band, The Accountants. Their music is “pure, serious rock and roll” with lyrics that address the experiences of “anyone who has spent at least five minutes in corporate America.” For more info, see (www.cparock.com).

HER WORKS PRAISE HER: A History of Jewish Women

in America from Colonial Times to the Present

By Hasia R. Diner and Beryl Lieff Benderly CW’64 G’66.

New York: Basic Books, 2002. 450pp., $35.00. Order this book

Ever since Peter Stuyvesant grudgingly admitted a band of 23 Jews to colonial New Amsterdam, Jewish women have played a major role in building the distinctive culture of the United States. Exploring the lives of several ordinary but remarkable Jewish women since 1654, this book chronicles 15 generations of change and tradition, courage and creativity. Drawing on long-neglected public records, private diaries, memoirs, and letters, the authors depict complex portraits of well-known figures like Ruth Bader Ginsberg, Emma Lazarus, Ms. Wyatt Earp, Bess Myerson, and Betty Friedan, as well as lesser-known leaders of movements for civil rights and social justice. Beryl Lieff Benderly, a journalist and author of seven books, lives in Washington D.C.

UP FROM INVISIBILITY: Lesbians, Gay Men, and the Media in America

By Larry Gross, Faculty.

New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

295 pp., $18.50. Order this book

Half a century ago gay men and lesbians were all but invisible in the media and, in turn, popular culture. While the lesbian and gay liberation movement has given gay people a more dominant role on the media’s stage, the question remains: Does the emerging visibility of gay men and women do justice to the complexity and variety of their experiences? While positive representations of gays and lesbians are a cautious step in the right direction, in this book Dr. Larry Gross argues that the entertainment and news media betray a lingering inability to embrace the complex reality of gay identity. Gross is the Sol Worth Professor of Communication at the Annenberg School for Communication and author of several books, including Contested Closets: The Politics and Ethics of Outing.

BRAIN CIRCUITRY AND SIGNALING IN PSYCHIATRY:

Basic Science and Clinical Implications

By Gary B. Kaplan C’ 79 and Ronald P. Hammer Jr.

Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

288 pp., $45.00. Order this book

The 1990s were appropriately termed “the decade of the brain” for their unprecedented advances in psychiatric neuroscience. This book links these recent findings in neuroscience with their implications for the treatment of specific psychiatric disorders: schizophrenia, addiction, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and Dementia/Alzheimer’s disease. Bringing together the contributions of 15 experts in the field, it provides “the mental-Velcro on which to add new information in clinical neuroscience as it becomes available at an ever-accelerating pace.” Dr. Gary Kaplan is associate professor in the departments of psychiatry and human behavior and molecular pharmacology, physiology, and biotechnology at Brown University School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Providence, Rhode Island.

FIERCE LEGION OF FRIENDS:

A History of Human Rights Campaigns and Campaigners

By Linda Rabben CGS’74.

Brentwood, Md.: The Quixote Center, 2002.

272 pp., $20.00.

The United States’ first human-rights campaign, to end the slave trade, ran from 1787 to 1792, and continued on through later generations until the abolition of slavery in the 19th century. In this new history of activism the author shows how these campaigns and others provided a template for today’s struggles to end the death penalty, guarantee workers’ and women’s rights, stop genocide, and rescue forgotten political prisoners. Dr. Linda Rabben is the author of Unnatural Selection: The Yanomami, the Kayapo and the Onslaught of Civilisation, and co-editor of Rome Has Spoken: A Guide to Forgotten Papal Statements and How They Have Changed through the Centuries.

THE ANTIBIOTIC PARADOX:

How the Misuse of Antibiotics Destroys Their Curative Powers

By Stuart B. Levy M’65.

Cambridge, Mass.: Perseus Publishing, 2002.

353 pp., $17.50. Order this book

Chilling media reports about anthrax and bioterrorism have helped make antibiotics all the rage among health-conscious Americans. Yet, this book warns that as families stock up on antibacterial soaps, toys, and cleansers, the effort to defeat threatening microbes may lead instead to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Dr. Stuart Levy, professor of medicine and of molecular biology and microbiology, is the director of the Center for Adaptation Genetics and Drug Resistance at Tufts University School of Medicine [“Resistance Fighter,” September/ October 2000].

WWII FROM MY VANTAGE POINT

By Ray Petit W’49.

New Jersey: Bowker, 2001. 128 pp., $9.95.

Detailing the everyday valor and squalor of World War II, this journal began as a collection of notes scribbled on pages of Lord Baltimore Service tablets, carried with the author from the time of his 1942 departure to Europe with the U.S. Army Air Corps to the end of the war in 1945. In it, Ray Petit describes being strafed as he returned from breakfast near the Cassino (Italy) beachhead, wriggling into the ball on the very top of Saint Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, and climbing to the top of the leaning tower of Pisa, trying to spot a field kitchen for food that night. But “the tedium and discomforts” of war were, as he writes in his foreword, a “small price” for American freedom. Now in business with Terrific Tubs, a flower-container service he copyrighted, the author and his wife, Doris, live in New Jersey.