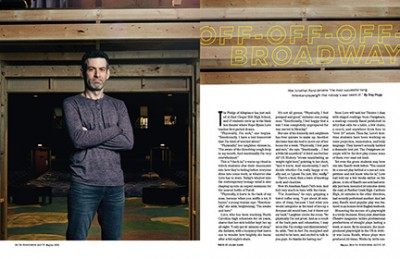

How Jonathan Rand became “the most successful living American playwright that nobody’s ever heard of.”

BY TREY POPP | Photo by Jillian Clark

The Pledge of Allegiance has just ended at East Chapel Hill High School, and 27 students circle up in the black box theater where Hope Hynes Love teaches first-period drama.

“Physically, I’m sick,” one begins. “Emotionally, I have a test tomorrow that I’m kind of worried about.”

“Physically,” her neighbor chimes in, “I’m aware of the dissolving cough drop in my mouth. And emotionally I’m very overwhelmed.”

This is “check-in,” a warm-up ritual in which students clue their classmates into how they’re feeling before everyone dives into scene work, or whatever else Love has in store. Today’s window into the contemporary teenage mind is also shaping up into an urgent summons for the nearest bottle of Purell.

“Physically, it hurts in the back of my nose, because when you sniffle a lot, it burns,” a young woman says. “Emotionally,” she adds, brightening, “I’m awake and here.”

Love, who has been teaching North Carolina high schoolers for 24 years, shares that her sick toddler kept her up all night. “I only got 45 minutes of sleep,” she declares, with a buoyancy that leaves one to wonder how brightly she burns after a full night’s share.

It’s not all germs. “Physically, I feel pumped and good,” exclaims one young man. “Emotionally, I feel happy that a test I was completely unprepared for was moved to Monday.”

But one of his formerly sick neighbors has four quizzes to make up. Another discloses that she had to move out of her house for a week. “Physically, I feel pale and sore,” she says. “Emotionally … I feel a little bit unsettled.” A third can feel her AP US History “stress manifesting as weight right here,” pointing to her chest, “and it hurts. And emotionally, I can’t decide whether I’m really happy or really sad, so I guess I’m just, like, really.”

There’s a beat, then a wave of knowing nods and chuckles.

Now it’s Jonathan Rand C’02’s turn. And he’s very much in tune with the room.

“I’m Jonathan,” he says, gripping a travel coffee mug. “I got about 35 minutes of sleep, because I had what you would categorize as the kind of hiccup a five-year-old would have, but it threw out my back.” Laughter circles the room. “So physically I’m not great. And as a result of the back pain and exhaustion, I may seem like I’m stodgy and disinterested,” he adds, “but in fact I’m energized and excited to be here, and excited to talk to you guys. So thanks for having me.”

Soon Love will task her Theatre 1 class with staged readings from Crazytown, a madcap comedy Rand published in 2013 that calls for a table, a few chairs, a couch, and anywhere from four to “over 70” actors. Thus far, Love’s first-time students have been working on voice projection, enunciation, and body language. They haven’t actually tackled a dramatic text yet. The Crazytown excerpts will be the first play scenes some of them ever read out loud.

Yet even the green students may have run into Rand’s work before. “You cannot do a one-act play festival or a one-act competition and not know who he is,” Love had told me a few weeks earlier on the phone. A trio of Rand’s one-acts had actually just been mounted 20 minutes down the road, at Panther Creek High. Carrboro High, 20 minutes in the other direction, had recently performed another. And last year, Rand’s most popular play was featured in an honors-level English textbook.

Measuring the success of a playwright is a tricky business. Every year American Theatre magazine tallies professional productions of straight plays lasting a week or more. By its measure, the most-produced playwright in the US in 2018–19 was Lucas Hnath, whose plays were produced 33 times. Works by 20th-century giants August Wilson and Tennessee Williams were put on 16 and 10 times, respectively. William Shakespeare, the US’s “true most-produced playwright,” tallied 96 productions. (Hamilton recently passed 2,500 total performances by its New York and touring companies—but Broadway musicals are something else entirely.)

Jonathan Rand has completed two dozen plays since self-publishing his first from his freshman single in the Quad in 1998. Collectively they have been produced more than 12,000 times in 64 countries.

Yet if you Google his name, two of the top three results—plus the featured box in the upper right corner—will steer you toward “Johnathan Rand,” a pseudonym used by a Michigan-based author of teen pulp horror and beginner chapter books for first-graders.

The actual Jonathan Rand also upended the business of theatrical publishing as a prototypical dorm-room coder, radically democratizing a marketplace whose incumbents were eventually forced to adapt. The company he founded, with his brother Doug, has exposed more than 1,400 playwrights to directors and producers in more than 100 countries. Along the way, Jonathan has managed to pull off a feat that, among playwrights, is rarer than a Tony or Obie nomination: earning a living exclusively through his scripts. Even at the pinnacle of the profession, most contemporary playwrights lean heavily on other sources of income: teaching, fellowships, residencies, TV work. Take Hnath. American Theatre magazine’s most-produced playwright for 2018-19 has an Obie Award, Guggenheim Fellowship, and a bevy of other honors to his credit, and teaches at New York University.

So how come Rand struggles to out-Google the nonexistent author of Mutant Mammoths of Montana and Dollar $tore Danny and the Shampoo Shark Attack? “He’s the most successful living American playwright that nobody’s ever heard of,” his brother says. There’s a reason. It’s the same one that explains why you’re not likely to find his name on American Theatre’s annual Top 20 list, or a playbill at some edgy East Village theater: Jonathan Rand dominates the least-vaunted—but furthest-reaching—niche of American drama: the high-school straight play.

Or as he puts it, “I’m not a famous playwright, unless you’re a 16-year-old drama nerd.”

Before Rand became a 16-year-old drama nerd in his own right, he was an awkward middle-schooler tormented by classmates for ears that stuck out too far from his head.

“I remember being in this Scrabble competition,” he told me after our morning at East Chapel Hill High, “and being about to blow our chances because I thought it was the last turn of the game, when in fact there was going to be one more. Because the whole time, right out the window, this kid in our class had his face pressed to the glass making his hands flop around like Dumbo ears.”

There was much to fear about the impending reality of ninth grade in Jacksonville, Florida. But also hope of salvation. Doug Rand, three years Jonathan’s elder, had become something of a thespian stud at Stanton College Preparatory School, the public magnet school where Jonathan was headed. And theater was a family enthusiasm. Jacksonville wasn’t exactly brimming with marquees but its dinner theater—the Alhambra, which is still in business—was a regular destination for Robin and Marco Rand D’74 and their three children. (The youngest, Lisa Rand Gr’16, later earned a PhD in the history and sociology of science at Penn.)

“I remember we went to see 1776,” Jonathan says. “I was probably seven or eight, and it was just jaw-dropping.” His maternal grandfather built sets on Broadway, and ran tech for soap operas and variety shows, including The Muppet Show. When the Rand kids were young he worked for the New York Ballet, where, during occasional visits, he captivated them with peeks behind the curtain. “He would show us all the magic of how the Sugar Plum Fairy glided across the stage, or how the giant Christmas tree rose from under the stage to become this thing that seemed four stories tall,” Jonathan recalls. “If I had to trace back where my interest in theatre started, it was probably that.”

His tween years brimmed with day camps full of “pottery and xylophones and presumably horrible theatrical productions for the parents on the final day.” And once he reached high school, he set his sneakers firmly in Doug’s footprints.

“Jonathan was kind of a big, gangling, goofy guy with a smart but twisted sense of humor,” recalls his drama teacher, Jeff Grove, who still teaches at Stanton. “And I liked it. It played into a lot of things I did. He found a way to have fun, but in the right way—staying on topic, making it fit what was going on in class. He knew how to have a good time and keep it appropriate.”

Jonathan was cast in the first musical he auditioned for—as Rapunzel in Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods. “Video evidence would prove that I was very off-key,” he says, “But I still had a great time … and I think that just played such an enormous role in building confidence for a scrawny young teenager.”

In time he figured out how to stay in key, and do quite a bit more. Grove still reminisces about the way Rand carried a run of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged), a three-man romp through all 37 comedies, histories, and tragedies in an hour-and-a-half. “This was a wild comedy,” Grove says, “and it even has an element of improvisation built into it—there are things that are going to be different every night, based on audience response. It also requires the actors, several times, to play some Shakespeare absolutely straight. So in this one show he had to do Shakespeare straight, he had to do an almost Robin Williams or Monty Python sort of zaniness, and he had to be able to improvise quickly and well. And he covered the bases. There was just nothing that he couldn’t do in that show.”

The thrill of acting, admixed with a standard mid–1990s dosage of Simpsons episodes, eventually pushed Rand to try his luck writing a one-act comedy. Technically, he’d had his first crack at playwrighting in sixth grade, with a three-page effort titled Nightmare on Sesame Street. (“I uncovered it recently. It’s horrible.”) But as a high-school junior, Jonathan again looked to follow his brother’s lead.

With Grove’s encouragement, Doug had helped launch a student-run evening of one-act plays at Stanton. Students did everything—wrote the plays, directed them, acted, ran tech, sold tickets, the works. One of Doug’s plays went on to win a national student-playwriting competition. As a perk of victory it was published by Dramatics magazine (“the Wall Street Journal of high school theatre,” as one teacher described it to me), and was subsequently included in a hard-cover anthology. So by the time Doug was in college, every few months he’d get a modest check reflecting royalties earned from a handful of performances.

For class, Jonathan had written a stand-alone sketch-comedy-style scene about a job interview that had gotten some laughs. He spun that into Hard Candy, a cascade of increasingly unhinged bids for employment that ended up winning the same contest Doug had won before. It too appeared in Dramatics—but no one ever put out a second anthology volume, so it never found its way into a proper book. Jonathan submitted it to traditional play publishers, but none bit. So he put it in a drawer, kept acting in school plays, applied to Penn, “and just sort of went about my hunt for what my major would be, and what I was going to do with my life.”

He cast his net wide enough to encompass music, astronomy, political communications, criminology, economics—and, significantly, computer coding.

The internet circa 1998, when he first arrived at Penn, was only just beginning to move past its email-and-bulletin-board phase. Never mind social media; the term weblog was only a year old, and creating one took some know-how.

“There was no Squarespace,” Rand recalls, referring to one of the website-building platforms that simplified everything in the early 2000s. “But Penn was giving some tiny amount of server space to any enterprising coders who wanted to toy around with it.”

So Rand made a website. Fittingly for a freshly minted member of the Glee Club, he stuffed it with links to his favorite a cappella groups. “It was very cheesy,” he laughs. But it also included the first four scenes of Hard Candy. “Essentially it said, ‘If you want to read the rest of the play, email me. And then if you want to perform it, send me a check to Ware College House, PO Box 380—or whatever it was.”

Then he went back to throwing darts at the course catalogue, hoping that some corner of the liberal arts would reveal the trailhead to a career path.

Three thousand miles away, in Visalia, California, Mike Wilson was facing the same challenge that dogged every high-school drama teacher staring down the barrel of their umpteenth production of Arsenic and Old Lace.

As longtime Dramatics editor Don Corathers once put it, “Most high school teachers need a big cast, lots of female roles, and something that won’t scare your grandma.” And virtually no American play written since World War II meets those criteria.

Consider three dramas widely regarded as the most important of the 20th century. Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire portrays the mental breakdown of a woman who is raped by her brother-in-law. Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night illustrates the author’s tortured youth with an alcoholic father and a drug-addicted mother. Tony Kushner’s Angels in America is a seven-hour examination of AIDS and homosexuality featuring a pill-popping Mormon, a fallen angel, and a right-wing Antichrist.

Grandma is already quivering at the fire exit—and we haven’t even gotten to the 152 f-bombs in David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross.

Meanwhile, playwrights targeting the high school market were by and large churning out stilted scripts that grated like bad ABC AfterSchool Specials. “They were old men writing really cheesy dialogue based on what they thought teenagers were saying,” Rand recalls. “You know: ‘Cowabunga, Dad! If I want to drink and drive, I’ll drink and drive!’”

“When I started teaching drama in 1979,” Wilson told me, “finding good, clean, funny plays was almost impossible.”

In Florida, Jeff Grove felt the same pain. “We were working back then from paper catalogues that publishing houses would put out. And you would have a one-paragraph description of a play’s story,” with limited information about the casting requirements. “But you would have to buy a copy of the script, plus shipping and handling, to see it. And it was very frustrating. A lot of us talked about how many times we bought scripts and felt we’d wasted money. You had to buy a ton of scripts to find that one nugget of gold.”

There were 1,500 kids at Wilson’s central valley school, Golden West High, and as many as 300 at a time were in drama. “I couldn’t find large-cast plays,” he told me, “so I’d do one-acts.” Those weren’t much easier to find, either—until, suddenly, one was.

“A student of mine found this play called Hard Candy on the internet,” Wilson recalls. “And it was hilarious!” He was confused about how to pay royalties—and buying anything on the internet still seemed sketchy to him—but Golden West ended up mounting a production.

And Wilson wasn’t alone.

Though Rand didn’t realize it at first, the website he made on a freshman-year whim had set the stage for an unexpected natural experiment.

“Doug’s play was by all traditional measures a success,” he reflects. “His play was great. It was published by a real publisher. And it was being produced five to 10 times a year in the US and Canada. And here I am in my dorm room, doing no marketing, and not published, and Hard Candy that first year was produced over 100 times in 12 countries.”

That summer, as Jonathan strung together temp jobs back home in Jacksonville, “Doug and I just sort of looked at the numbers and said, ‘What is going on?’”

The answer wasn’t very complicated: Theatrical publishing companies were still doing business like it was 1940. It struck the Rands that maybe what they’d stumbled across wasn’t just a good formula for a one-act comedy, but an entirely new business model.

Back on campus for his sophomore year, Jonathan looked for other plays to publish. He loved one by a classmate in a playwriting class, Adam Fisch C’99 (who now practices neurology in Indiana). Another came by way of Doug’s Harvard acquaintance Nick Stoller, who later directed the Hollywood comedies Forgetting Sarah Marshall and Get Him to the Greek. They knew that Jeff Grove had written a play years before, so they signed their former drama teacher. In the beginning, they paid their bills with wages Jonathan had saved from a high school job at a local bagel shop.

Meanwhile, Harold Prince C’48 Hon’71 visited campus to give a talk, and Jonathan managed to put his face in front of the legendary Broadway producer afterward. “I sort of did a pitch for Playscripts, our company, and he was immediately intrigued, and gave me his card.”

The Rands soon found themselves in Prince’s Rockefeller Center office. “He immediately got the concept and what we were trying to do,” Jonathan recalls. “And he was just like, ‘What can I do to help?’”

Well, we’re looking for new writers, the brothers replied.

“‘Absolutely,’” Jonathan remembers Prince responding. “‘My assistant Brad is going to hook you up with some amazing new writers. What else can I do?’ I mean, he just couldn’t stop being generous.”

Prince became the first member of Playscripts’ advisory board—and set about stacking it with a who’s who of American drama.

Jonathan was in High Rise East when a Los Angeles number popped up on his Motorola StarTAC cellphone. “I pick it up, and it’s Neil Simon,” he says. “And I’m just trembling, because this is the guy who meant everything to me in high school.” They talked for an hour, and Simon joined the board. “And Stephen Schwartz, and Alfred Uhry, and David Henry Hwang, and Terrence McNally—all these just unbelievable people. Tony Kushner! And the majority of our advisory board was just a matter of Hal Prince calling up these people and being like, ‘You’ve got to talk to these Rand brothers. They’re really innovative, and they’re disrupting the space, and you guys should help.’”

So, fueled by bagel money and the titans of 20th-century theatre, Playscripts started gaining speed.

The company’s main innovation was to let customers sample plays freely—reading up to 90 percent of them online—before committing to buy scripts and production rights. They also built a search function that guided prospective directors and producers toward exactly what they needed. Looking for an all-female political farce inspired by The Taming of the Shrew? A Jane Austen adaptation with an a cappella angle? A one-act comedic murder mystery suitable for middle schoolers? Just plug in the variables.

When Mike Wilson found his way to Playscripts’ website he still shied away from online transactions, but the catalogue was too good to pass up. He became a serial customer who did payments over the phone, until, some years later, he and his wife showed up unannounced at Rand’s office while visiting New York. “I just told him flat out: ‘Your plays have basically saved my program.’”

Grove became a customer too—and, well into the middle of his career as a drama teacher, a successful playwright. After he and his coauthor rewrote the play the Rands had asked to publish, “the first copy sold within a week, and we had our first production within a month,” he says. “And this is not a play anyone would ever have heard of, or be looking for. And we were certainly not authors that anyone would be looking for.”

He went on to write and publish six more one-acts through Playscripts. Over the years, they’ve been produced more than 400 times.

“When you’re a teacher,” Grove marvels, “how often does one of your students come back and offer you a chance to make money doing something you taught them how to do?”

At Penn, Jonathan kept singing, acting, and leaving a wake of laughter wherever his deadpan humor found purchase. “He was a well-meaning and sweetheart of a guy, who also happened to be funny as hell—and not just the writing,” recalls Jonathan Adler W’02, with whom Rand shared the third floor of a Pine Street rental house. To Adler, Rand was a master of the “dry, funny joke told with a straight face.”

To fellow Glee Clubber Piers Platt C’02, Rand was “a duality”: “ridiculously hilarious in almost any context” but “actually a fairly quiet guy.”

“Jon never gave me the impression that he was doing it for attention,” Platt says. “He was surgical with his humor—not dominating.”

To fellow housemate Suzana Berger C’02, he was a great listener who was “very amusing and entertaining, but never at anyone’s expense.”

“He was also a real actor, and I was not,” adds Berger, who bonded with Rand during auditions for a Penn Players’ production of Pippin, and is currently the founding artistic director of Dragon’s Eye Theatre, a Philadelphia based nonprofit that develops and produces plays for children.

Yet as Rand neared graduation, he began to retreat from the stage. “I realized that if you want to reach the apex of success as an actor—if you’re really going to make it—you have to be prepared to be famous,” he says. “And that’s not my personality type.”

For four years, he’d spent most of his free time either performing or trying to grow Playscripts—but he hadn’t managed to write another play of his own. That changed one day in the rooftop lounge of High Rise East during senior year, when a laptop crash plunged him into the rare circumstance of having nothing to do. He started scribbling on a pad of paper, and soon the germ of an idea began to blossom: a series of blind dates, each more disastrous than the one before, that unfold in the same white-table restaurant. A girl suffers through dinner with an egomaniac who won’t stop talking about ultraviolent action movies. A guy tries hard to be polite to a girl who spends their whole meal listening to a Bears game through an earpiece. There’s a mime who refuses to speak, a method actor who’s just using his date to research a role. A girl finds herself opposite a man wearing only a burlap sack.

The resemblance to Hard Candy was more than structural. “ Hard Candy is about a series of job interviews—and I’d never been on a job interview when I wrote that,” Rand says. “I had never been on a blind date when I wrote Check Please … and it sort of shows. I clearly had a very warped sense of what blind dates were like at age 21.

“But it was really less about the dates being the impetus, but the characters. And a lot of those people are Penn people. I won’t reveal their names,” he laughs.

Except for one.

“No one actually had a burlap sack. But that’s my buddy Mark Glassman [C’00 CGS’01], who slept on our couch a lot in High Rise East. He was also one of my roommates in New York in the early days. I just pictured him in a burlap sack—I pictured him being funny as a guy in a burlap sack.”

Nearly 20 years later, Rand semi-disparages Check Please as the “Piano Man” of his oeuvre. He’s kind of sick of it, much as Billy Joel might tire of requests for his hoary barroom ballad—but if any one play cemented Playscripts’ place in theatrical licensing and publishing, it’s Check Please. According to Dramatics magazine’s annual survey, it’s been the most produced short play in American schools for 14 consecutive years. (Some years, Rand has had as many as four of the top ten short plays, and Playscripts properties have held as many as nine spots. The company also publishes full-length plays, including several by playwrights on American Theatre’s most-professional-productions list.)

Hard Candy and Check Please shared many characteristics that made them uniquely well suited to high school productions. They had enough characters to satisfy a drama program’s need to maximize participation, yet the episodic scenes, usually depicting two- or three-person interactions, were a logistical boon for drama teachers. “If one of their students is at volleyball practice and the other one’s got the student government meeting, the whole rehearsal isn’t ruined,” Rand says. “You can still rehearse a bunch of other scenes.”

The sets were simple. Male and female roles were largely interchangeable—no small matter given that girls usually outnumber boys among high school thespians. Having grown up in the Deep South, Rand was all too familiar with how narrowly most US communities set the guardrails for high school drama. “I won’t drop an f-bomb. I won’t have characters have onstage sex or whip out an AR-15—you know, all the things you can’t do at a school.”

But none of that mattered without the critical element: the plays were legitimately funny. And a big reason why is that Rand doggedly refused to ask himself the great laughter-killing question: What would teens like?

“I know that most people who are performing these plays are going to be 18 or under. But I’m not trying to write down to anybody,” he says. “What I’ve always tried to do is write something that’s going to make my peers laugh.

“By and large, I’m writing older characters. I think there’s this sense that teens want to play teens. And they sometimes do. But you know, a lot of teenagers are binge-watching Friends right now, and that’s about 20-somethings in New York. I think for high school kids, [ Check Please] is almost like a period piece. It’s like, ‘Oh, I can act like I’m a 20-something in the early 2000s or 1990s on a dinner date. Isn’t that quaint!’”

And after all, inhabiting an alien personality is what acting is all about.

Rand’s body of work now stretches from comedic whodunit (Murder in the Knife Room), to media parody (Action News: Now With 10% More Action!), to Law & Order: Nursery Rhyme Unit, a puns-gone-wild criminal justice caper that features Peter Piper, Old MacDonald, and sounds almost exactly like you’d imagine (“Chuh-Chunk!”).

That last one is a good illustration of his signature move, which, as he described it to another group of students during our February swing through three North Carolina high schools, is to “take something dead serious and apply it to something that’s not serious at all.” So, The Future is in Your Tiny Hands presents a gloves-off presidential debate—between elementary school student council candidates obsessed with tater tots and pigtail-pulling. The Least Offensive Play in the Whole Darn World takes aim at community censorship of high-school theatre productions, by way of a fast-talking sales pitch for the ScriptCleaner5000—which scrubs the blood out of Shakespeare, the infanticide from Greek tragedy, and everything but a single strum of the guitar from Rent.

“The kind of genre that Jonathan writes is absolutely necessary,” Love says. “There are a lot of communities whose middle is pretty conservative about what they want their kids saying, what they want them portraying.”

Love’s program is atypical. Chapel Hill is an island of progressivism in conservative North Carolina, and Love has cultivated enough community trust to be able to stage plays like The Laramie Project, about the aftermath of the 1998 murder of gay University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard. Most US drama teachers would lose their jobs if they tried to push the envelope half as far. Mike Wilson’s production of Les Miserables sold out six performances at a 1,200-seat theatre, “but you can’t believe the accusations and criticisms” from local parents angered by the prospect of schoolgirls singing the bordello-themed “Lovely Ladies.” Just down the road in Cary, NC, a production of the decidedly PG Legally Blonde got “a lot of pushback,” drama teacher Bing Cox told me, simply because it includes a character who is gay.

(The strictures of theatrical licensing forbid any alteration to the script without explicit permission from the playwright or copyright holder. Rand is typically flexible to such queries, and even includes alternative lines in some scripts where dialogue pushes against the edge. But he has held the line against requests to elide a character’s homosexual identity from his plays. Many schools have attempted to bowdlerize such a character from Check Please—which contains no sexually explicit content. “I refuse,” he says. “I tell them that if they object to the fact that there are people in the world who are gay, they need to find another play.”)

“If you’re only allowed to do things that have characters that are likeable,” Love continues, “and that don’t swear, and don’t have affairs, and don’t die … that does not make for a lot of teaching opportunities about the kinds of choices that face an actor trying to give a role psychological depth.”

This spring, Love’s students are putting on a play called Our Town 2. “My kids are doing the table work of what would it be like to have gay parents and have the state challenge the legality of that—for you to be taken out of your house and go into foster care at 12 years old because the larger society disagrees with your parents’ sexual orientation. That’s complex emotional stuff. But they still have to look at the lines on the page and go, ‘What’s underneath that? What can I add, as an actor, from my imagination, from my body and from my voice?’

“What distinguishes Jonathan’s stuff,” she goes on, “is that even in communities that don’t want their kids going into that emotionally murky territory, his stuff is so smart and clever that there are little gems for kids to find. And that’s the work you’re trying to teach actors to do!”

Rand occasionally reflects on a remark he once heard the iconic American playwright Edward Albee offer at a literary conference: “There’s no place for safe theater.”

“He said, ‘Unless it’s unsafe, it’s garbage,’” Rand recalls. “And I didn’t challenge him on it—because he’s Edward Albee. But you can’t just leap into Bertolt Brecht. You need stepping stones! That’s actually why I think I made a career of this—students need something that is a combination of feasible but also of a quality that’s not going to bore them.”

“Poor writing lays it out for audience and lays it out for the kids,” Love says. “Jon’s writing is smooth enough that you can just say the line flat, and say it with a funny voice as Little Bo Peep, and it will work. But if you also go, ‘Wait a second, this is making a reference to film noir!’—then the kid can go do that table work: what does film noir look like, what are the modifications to your body and voice that make it film noir, and you’re playing that joke that Jonathan has hidden in this little gem.”

“Parents still want to see their children on stage doing things that make them proud,” she winds up. “That’s not theatrically interesting! But Jonathan makes those parameters super theatrically interesting. And that’s not easy. It’s a little like Dr. Seuss: the man made a 50-word list into an opus. That’s a little like what Jonathan has to do for the market he’s serving. He lets those programs play to the top of their intelligence as artists.”

Over the course of the morning in East Chapel Hill High, students reveal other reasons why Rand’s work has gained a lasting foothold in high school drama.

In a Q&A with Rand, Love’s Theatre 4 students discuss the one-acts they’re producing for a spring festival. One is a “religious parody,” another plumbs the relationship between “an autistic character and a neurotypical one,” and a third focuses on immigrant restaurant laborers.

Like high schoolers everywhere, these kids have a lot on their minds. Indeed, Rand might keep assault weapons out of his scripts, but a weapon threat on social media had roiled this campus the previous day. Nevertheless, the coming festival’s slate was mostly dedicated to comedy.

“I’m sure everybody here wanted to do a social drama about injustice,” explains 11th-grader Ivy Evers. “But we want to put on a finished product that gives our production a good name, that provides the foundation to have some serious conversations—and to provide the audience with relief from that, so they can have space to digest those things and fully absorb them … And also I think comedies are easier to put on as a finished product at this level.”

Her classmate Nadia Zabala agrees. “With comedies, the writer is doing most of the work. You say it, and the audience laughs,” she says. That makes for steadier ground for a first- or second-time actor—not to mention a first-time student director.

But the “flip side,” Evers adds, “is that at this age it’s harder to make kids laugh than it is to make them cry. So I think comedies are easier to put on as a finished product as this level—but they’re harder to make funny.”

Rand seems to have the knack. The Theatre 1 kids who file into class the next period are less experienced, but every bit as embroiled in the turmoil of teenage life. One student is particularly out of sorts. It emerges that a friend has arrived on campus high, confronting him with a rotten choice: find help from the school nurse, triggering a suspension and possibly something even worse at home; or help his friend conceal it, risking complicity in whatever consequences that might bring. “Emotionally, I’m pissed,” he offers by way of check-in.

As he circles up with three classmates to read their assigned Crazytown excerpt, every sign points to disaster. His tone is sour and his body language defiant—rare is the teenager who can escape the urge to perform himself. This group is going to be sucked into his whirlpool, and there’s nothing to prevent it. Yet as their first fits and starts lead them deeper into the scene, he starts giggling despite himself, and so does everyone else. The crisis hasn’t passed, but the play has given him a moment, at least, of reprieve.

Virtually every writer sooner or later faces doubts about the ultimate value of his or her work. Rand is no different. He and Doug sold Playscripts a few years ago, right around the time Jonathan and his wife Concetta had their first child. (Doug, who had landed a job as assistant director for entrepreneurship in the Obama White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, had even less time to devote to the business.) The world is full of pediatric-acute-care nurses, firefighters, and cancer researchers. It has also honored certain writers with Obies, and Oscars, and Pulitzers. Meanwhile Rand has written a couple dozen plays produced overwhelmingly by underaged amateurs.

“At the end of the day, they’re just high school plays,” he says. “But then I see some kid who was as awkward as I was shine in a production. Or I hear some amazing story from a drama teacher about how some shy girl blossomed in a silly comedy I wrote.” And then it doesn’t seem so small.

“I don’t care what you say,” Mike Wilson told me. “These kids from 14 to 18 are incredibly insecure, whether they want to admit it or not. But if you stand up in front of 300 people, and you’re making 300 people laugh—the kids come off the stage so energized, giving each other high fives, they’re hugging each other! It’s just such a bonding thing. And it makes them feel good about themselves. In this day and age, of cyberbullying and everything else, there are just so many benefits to drama productions.”

One of them, which is rarely remarked upon in a culture conditioned to equate acting with artifice, is that the tools of dramatic self-presentation can carry over into realms of great consequence—sometimes in astonishing ways. There is perhaps no more galvanizing example than what happened in the wake of the 2018 mass shooting at Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High.

The survivors of that massacre who emerged as student leaders of the Never Again movement—who have sparked the most widespread gun-control activism in a generation or more—were a diverse group. But one thing many had in common was training from their school’s renowned drama program. As Slate legal affairs columnist Dahlia Lithwick observed, “these poised, articulate, well-informed, and seemingly preternaturally mature student leaders … have been so staggeringly powerful, they ended up fueling laughable claims about crisis actors.” But the truth was that they’d mastered some of the skills of regular actors—just of the high school variety.

It turns out that Marjory Stoneman Douglas High was one of the first schools to perform Hard Candy, back “in the old days,” Rand says.

More recently, the Stoneman kids encountered the playwright on different terms. Two months after the shooting, students from neighboring North Broward Prep decided to cancel one of their own performances in order to support a production at Marjory Stoneman the same Friday night. The following evening, the Broward thespians invited their Stoneman peers to be special guests at their Saturday show. The hosts hoped to show solidarity with their counterparts—and also give them a reprieve.

The Stoneman kids graciously accepted. For high school drama nerds seeking a night of comic relief, there was nothing quite like tickets to a trio of one-acts by Jonathan Rand.

Great article. He’s a very talented man and we are proud to have him as our son-in-law!