An archaeologist figures out a sustainable way to save endangered sites.

If you’re willing to use some poetic license, you could say that the groundwork for the Sustainable Preservation Initiative (SPI) was laid nearly 2,000 years ago, when Mount Vesuvius erupted and buried the city of Pompeii under deep layers of volcanic ash and pumice. And that the seed was planted half a century ago, when Larry Coben Gr’12’s fourth-grade teacher told his class about those dramatic ruins. And that it was fertilized by his mother, who brought him a piece of pumice from a Pompeii structure (long story) that he kept on his nightstand for many years.

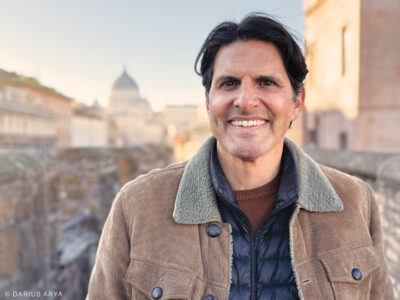

Fast-forward to the beginning of this century, when Coben, now a consulting scholar at the Penn Museum, decided to reroute the arc of his career, get his PhD in anthropology at Penn, and pursue his decades-old passion for archaeology. He was 40 then, and had accumulated a wealth of business experience, having founded and sold several energy firms and served as CEO of Bolivian Power Company. (He now chairs the board of NRG Energy.)

For his doctoral fieldwork, he began excavating the monumental Inca ruins of Incallajta, a 15th-century site in central Bolivia that had been the easternmost outpost of the Inca empire. Few people know about Incallajta, which is three hours by car from the nearest city (Cochabamba), in a region with very little running water, electricity—or money. When Coben started there in 2001, most rural Bolivians earned about a dollar a day.

That reality underscored a serious problem for archaeologists, which boils down to survival versus preservation. At Incallajta, farmers had planted crops in parts of the 67-hectare site, and were letting cattle graze in others. A walled field that had once been the largest single-roofed room in the Inca Empire was now host to soccer games.

“I would say to these people, ‘Please don’t grow crops here—it’s destructive,’” he recalls. “And, ‘Please don’t graze your cattle here.’ And they would say, ‘Yes, yes, yes.’ And of course it would keep going. Why would they give that up for some esoteric knowledge base that I, an outsider, was trying to teach them?”

But if the problem is an economic one, he notes, “shouldn’t the solution be economic as well?”

He proposed that the villagers would charge the few foreigners who came to the site 10 bucks apiece.

“They looked at me like I was insane,” he says. “Who would pay two weeks’ wages to go and see these rocks?” So he ponied up $50 for a gate across the road and a couple weeks’ wages for someone to mind it.

In the first two weeks, seven foreigners came and paid to see the ruins, which translated to $70 on a $50 investment. “What it really did was change the attitude of the people toward the site,” he says. “It wasn’t just some vast intangible part of their past. It was a sustainable economic asset for them.”

Soon the villagers bought out the people who were grazing and growing crops on the site. Then they built a new soccer field, away from the old ruins. They became increasingly interested in the history of Incallajta and wanted to protect it, says Coben, “because they were proud of it—and they could earn from it.” Some became guides.

After looking in vain for a nonprofit organization that was doing the sort of sustainable, community-enhancing work he had envisioned at Incallajta, he decided to start his own. And so, in 2010, he founded SPI, with the slogan build futures and save pasts. The idea, he says, was: “Let’s do a different kind of economic development, a sustainable one that preserves the site and utilizes it as a constant, ongoing, long-term asset. I cannot in good conscience tell people who were exploiting something to survive to stop doing it if I don’t offer them an alternative.”

So far, the nonprofit has launched 10 projects at archaeological sites in Peru, Guatemala, and Jordan, with the local communities producing ceramics, jewelry, and textiles, not to mention the spin-off businesses, such as blacksmiths.

The first project Coben chose was San José de Moro, an important cemetery site along the northern coast of Peru that’s famous for its Moche-era ceramics. (Bolivia was out, since the country under President Evo Morales was becoming increasingly difficult for Americans.) The site was supervised by Luis Jaime Castillo, one of Peru’s top archaeologists.

“He’d been working in this site for over 20 years,” says Coben, “and he could tell you he tried every traditional method of trying to preserve his site and engage the community—with no success.” The SPI approach made sense to Castillo, Coben notes, and “it worked so well that he’s now, in addition to being a professor at their university, our vice president for South America.”

According to SPI’s website (sustainablepreservation.org), the San José de Moro project has created 25 permanent jobs, 20 temporary jobs, and produced $50,000 in local economic impact. And the severe looting problem “has ground to a halt.”

The key to a project’s success is to “teach people not just how to make products but how to run businesses,” says Coben. “We’ve developed a mini-business school for people living in poor communities with no training. We teach things like tax and accounting and legal formalization and customer service and sourcing and production and marketing and sales—and make people understand that all of those skills are important. The natural instinct of community projects is that whoever makes the product gets the money. And that’s not a good way to run a business. There’s a reason that sales and marketing people are well compensated.”

It’s also “very important that these groups be led by people from their country,” he adds. “The notion of somebody coming from the US to do this doesn’t work.”

Three years ago, SPI partnered with National Geographic at Pachacamac, a UNESCO World Heritage Site near Lima, the sprawling capital whose growth has often encroached on the site’s territory. Working with the Pachacamac Site Museum in conjunction with National Geographic, SPI helped a group of local women form an organization called Sisan (“flowering,” in Quechua). They make and sell products related to Pachacamac’s cultural history.

“In their first year, they earned $10,000,” says Coben. “In their second year, they earned $17,000. That’s the kind of growth even Uber would kill for.”

SPI’s approach to architectural preservation has also been taken up by the Milken Institute, the economic think tank founded by Michael Milken WG’70, as a model for protecting archaeological sites in Israel.

Coben knows that he needs to empower as many women as possible—“because we’ve found that’s really a key to success.” He recalls a meeting in Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala, where the villagers now make and sell Mayan-style jewelry at the old Mayan site. At one point the husband of one of the jewelers asked to speak.

“He said, ‘When this project started, I told my wife I didn’t want her to work. If she was going to go, she had to make sure the house was clean, the kids were off at school and taken care of, the meals were made’—all of these typical macho things. And he said, ‘When I saw her earning money and being educated and the changes in her, I couldn’t believe who this wonderful new person was. My personal Berlin Wall fell.’”—SH