The chronicler of a remarkable Hollywood studio talks about the animated characters—real and drawn—that populate his new book.

Adam Abraham C’92 grew up watching cartoons: “Disney films, Looney Tunes, Tex Avery, Hanna-Barbera—whatever thrust itself into my suburban world,” he recalls. But it wasn’t until he was a “grownup” (the quotation marks are his) that he saw his first film by United Productions of America, or UPA, the remarkable studio that grew out of a bitter strike at the Walt Disney Studio and became a haven for talented animation artists.

Abraham’s reaction to that short 1953 film, The Tell-Tale Heart (based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe), “was a lot like what the studio’s original audiences must have felt in the early 1950s when UPA burst onto the scene,” he says. “I was pretty much blown away. It was such a pronounced shift from Bugs Bunny, Tom and Jerry, Heckle and Jeckle.”

UPA brought a fresh, modern aesthetic to the medium, while eschewing the “symphonies of violence and pain” that characterized so many cartoons from Warner Bros. The freedom enjoyed by its artists led to quirky, visually arresting films that featured such singular characters as Mr. Magoo and Gerald McBoing Boing (created by Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss). But the “left-leaning radicalism that spurred the growth of UPA also hastened its decline,” notes Abraham in the book’s preface, and some of the studio’s creators found themselves on the hot seat during the Cold War.

Given those elements, Abraham was soon hooked—and decided to write a book.

“I knew the bare outline of the UPA story,” he says, “and I was confident because it offered a classic three-act structure: the optimistic early years, the glorious heyday, and the ignominious fall.”

The result was When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA, published this past March by Wesleyan University Press. His considerable research, which included interviews with surviving UPA artists and executives as well as screenings of films and archival digging, yielded a book that is informative, detailed—and entertaining.

“When Magoo Flew is an academic book in that it’s producing new knowledge,” says Abraham, who has taught at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and now lives in York, England. “But I think I was able to tell the strange and surprising UPA story without resorting to words like dedifferentiate and heteronormativity.”

Abraham recently spoke by email with Gazette senior editor Samuel Hughes.

How did UPA, Disney, and some of the other studios you write about reflect American art and culture?

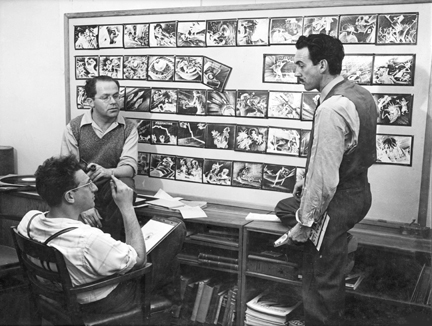

One of the reasons I knew that there would be a book and not merely an article in the UPA story is that it was impacted by the key events in mid-20th-century American life: the Great Depression, the Second World War, the anti-Communist mania of the Cold War era, the baby boom, suburban migration, a return to domesticity. The history of American animation is to some extent a cultural history of the nation that made these works possible. There would be no Walt Disney Studio—no Snow White, no Fantasia—without the Great Depression: it was the greatest hiring bonanza Walt and his brother could have hoped for. Brilliant visual artists, who in a more solvent era would have been gainfully employed, found their way to the Disney Studio. The three men who formed UPA—Steve Bosustow, David Hilberman, and Zachary Schwartz [pictured at right, right to left]—all worked for Disney in the 1930s for the excellent reason that there was work to be had.

As far as UPA is concerned, World War II was the engine that made the studio possible: it began producing military training and safety films from the start. And the McCarthy-era Commie-baiting played a significant role in diminishing UPA’s creative staff.

Who were your favorite characters in this saga, and why?

My goal was to be impartial; I tried not to pick favorites. Steve Bosustow was the president of UPA during its creative peak in the 1950s, yet he’s a somewhat divisive figure. In the ’50s and after, there was a lot of press that made him out to be the next Walt Disney. By coincidence, he looked a bit like Disney, and they wore the same mustache.

There was, of course, an anti-Bosustow backlash, which to some extent is still going on—that he was a boob and completely unimaginative. I tried to tell his story in a fair and clear-eyed manner. I am highly sympathetic to what he tried to do: create an environment in which artists were free to make their art. Bosustow may not have been the finest artist in the history of cinema, but he must have done something right or UPA never would have existed.

What was it like doing the research for it—watching the films, looking at the old gag drawings, interviewing the surviving characters, et cetera?

It was archaeology. The fundamental lesson of writing the UPA book is this: not everything is on the Internet. The research I did was decidedly analog. I traveled to Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, DC, and Dublin, Ireland to access materials or individuals. At one point I was climbing over dusty cardboard boxes in a poorly ventilated California apartment looking for animated gems. That day I found a few gag drawings that I’ve now published in the book. Not only are they still funny, they are also revealing about what life was like at the studio in the 1940s and ’50s.

As far as cartoons are concerned, when I began to research the UPA studio, its films were not commercially available on DVD. I screened bootleg copies in order to write the book. Then, in a remarkable piece of timing, Turner Classic Movies released a delightful box set of UPA’s classic cartoons in the same month that my book was published: March 2012.

At the beginning of this process, I interviewed an animation historian named Charles Solomon. He gave me a vital piece of advice: Don’t delay. Since I began this process, seven of my interview subjects have died. In some cases, my interviews may be the last they gave.

Do you have any favorite little-known films or characters?

I like Pete Hothead. He is constantly furious and completely unreasonable. He appeared in two of UPA’s theatrical shorts, Pete Hothead, from 1952, and Four Wheels No Breaks, from 1955. There is obviously a similarity to Mr. Magoo: both are ill-tempered and always jumping to the wrong conclusion. Of course, Pete Hothead never achieved the success of Magoo. More’s the pity.

What did Mr. Magoo represent and why was he important for UPA?

It’s hard to fathom today what a big star Mr. Magoo was. In the mid-1950s, he was considered one of the top box-office attractions. He won two Academy Awards. He was what we would now call a valuable brand. My reading of the character Magoo is that his blindness, which everyone remembers, is actually incidental. What is important about Magoo is his complete self-confidence, his assurance that the world is rationally organized, and his inability to perceive anything to the contrary. In the book I make the case that, as such, Mr. Magoo is an emblematic character for the 1950s, the decade of his greatest success.

What effect did TV have on animation and animation studios?

If TV didn’t kill the theatrical seven-minute short, then it at least served as an electronic graveyard. In the 1960s UPA ceased to be a progenitor of droll and Modernist cinematic experiments and instead became a purveyor of television product. The reason is that the studio was under new management. Never profitable under Steve Bosustow, the studio was sold to Henry Saperstein, whose background was in merchandising.

Of course, times were changing as well. Walt Disney discontinued his animated shorts, except for the occasional special; and Hanna and Barbera, as many people noticed, left M-G-M and became television producers.

How much UPA influence do you detect in more recent cartoons?

The influence is huge. The UPA influence is most pronounced in television animation. Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon are pretty much built on the graphic simplification and radicalization that UPA popularized. There are, I’m sure, cases where the artists don’t even know that they are influenced by UPA; they may be taking the lessons at second- or third-hand, or via the DNA of Hanna-Barbera, which incorporated UPA’s lessons in order to produce animation cheaper.

Anything else?

In March there was a screening of UPA cartoons at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A few hundred people sat in a theatre and watched 35mm prints of cartoons made decades ago, and they did not seem old! They were as fresh and funny as if they were produced last week. I didn’t make these films; I wasn’t even born then. But I was proud of UPA.