A brighter, more accessible Penn Museum hopes to attract “new audiences.”

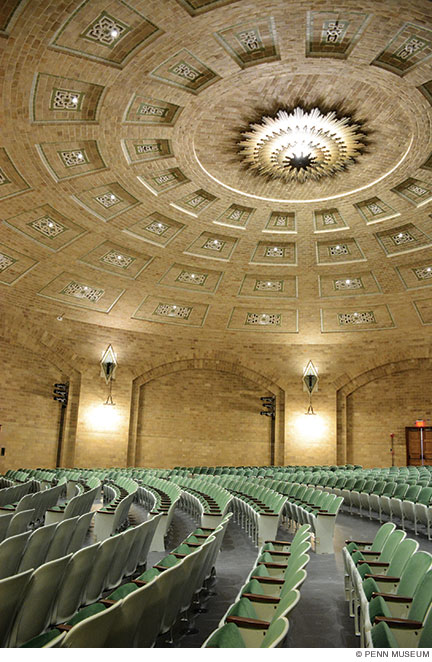

In mid-November, the Penn Museum unveiled the latest phase of its multiyear, more than $100-million Building Transformation project: new galleries and collections from Africa and Central America and Mexico, along with a renovated Harrison Auditorium and main entrance showcasing its famous Sphinx of the Pharaoh Ramses II.

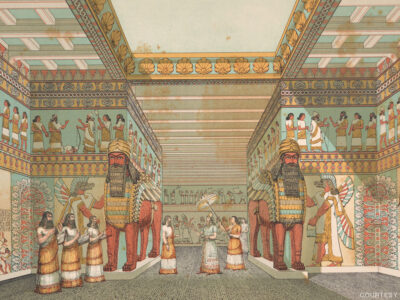

Julian Siggers, Williams Director of the Penn Museum, describes the ongoing project as an effort to make “one of the world’s great collections that tells our shared human story” more accessible and welcoming. The museum opened reimagined Middle East Galleries in April 2018 and plans to complete new galleries on Egypt and Nubia, Asia, Israel and its neighbors, and human evolution over the next few years.

Dan Rahimi, executive director of galleries, says the museum is competing for “new audiences” by “really upping our game in how we build galleries and how we present materials.” Among the obvious improvements: air conditioning, better lighting, and simpler, clearer exhibit labels geared toward visiting families rather than scholars. Touchscreen interactives convey more in-depth information, and works by contemporary artists help link past and present.

The latest renovations, encompassing more than 10,000 square feet, cost $33.5 million, according to museum officials. The museum also has expanded its Global Guides program, with guides who’ve lived in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Mexico, and Guatemala adding their perspectives to the revamped galleries.

The museum’s main entrance is now a more dramatic, airier space that bids visitors welcome in 19 languages and offers an immediate view of the massive red granite Sphinx of Ramses II, relocated last summer from the Egypt Gallery, where it had resided since 1926 [“Gazetteer,” Sep|Oct 2019].

Behind the sphinx is a rotating display of 10 objects introducing visitors to the museum’s 10 curatorial sections. Among the artifacts currently on view are a blue glazed faience canopic jar from ancient Egypt, used around 1375 BCE as a container for a temple singer’s mummified stomach; a late 19th or early 20th century wooden mask from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; and a contemporary piece by a Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, artist representing herself as both male and female and referencing Grant Wood’s American Gothic. An intimate adjoining gallery, whose objects also will rotate, spotlights two pairs of moccasins with decorations evoking both Native American hardship and resilience.

The 2,000-square-foot Mexico and Central America Gallery, renovated for the first time since 1949, displays the museum’s renowned Maya collection. But, with about 200 objects, it now embraces a range of other cultures, from the Olmec to the Aztec. “We had given lip service to the rest of the region, and I wanted that to change,” says Simon Martin, the gallery’s lead curator and a Maya expert.

Martin says that knocking down false walls increased gallery space by 30 percent. Enhancing the displays, he says, involved “re-excavating objects that were in our basement, liberating them from the dusty shelves, and also getting some loans from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.” One such loan is a rare sculpture of a Water Goddess from the city of Teotihuacan that still shows traces of red and green paint.

The artifacts are arrayed by culture, but with an eye to cross-cultural comparisons. Against dark backdrops, striking larger pieces are juxtaposed with smaller ones, creating a visual rhythm that makes the displays easier to scan. The Olmec vitrine, dominated by a sculpture of a childlike Maize God wrought in volcanic stone, is “a good example of that,” Martin says.

In designing the exhibition, Martin says he assumed that visitors had limited knowledge of the region. “They may have heard of the Aztec and Maya,” he says. “They’re very unlikely to know all the other cultures that we have on display here. My plan was to take people through a temporal journey and a geographic journey. And because this space is effectively a glorified corridor,” drawing visitors from both the museum café and the main entrance, “there are two entrances and no exit.”

One of the most historically important pieces in the Maya section is the carved limestone monument Stela 14, from Piedras Negras, in present-day Guatemala. Celebrating the ascension of a king in 758 CE, it was a key to the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs.

Other gallery highlights include Gulf Coast ceremonial paraphernalia from a ritual ballgame (still played in Mexico), as well as gold ornaments from Costa Rica and Panama, Olmec jade, Aztec sculptures, and memorial masks from the pyramid-packed city of Teotihuacan. One corner of the gallery, curated by associate curator and senior keeper of American Collections Lucy Fowler Williams, displays 20th-century Maya textiles and celebrates the continuity of Maya culture.

Past and present are also connected in the thematically organized, 4,000- square-foot Africa Galleries. Subtitled “From Maker to Museum,” they have been informed by visitor input gathered in connection with the 2011–18 “Imagine Africa” exhibition, according to Kate Quinn, the museum’s director of exhibitions and special programs.

One goal, Quinn says, was to spotlight the provenance of selected objects, along with their cultural meaning and how (and by whom) they were made. One touchscreen interactive details the paths that several artifacts took from Africa to Penn’s collections.

The displays, with about 300 artifacts representing 21 countries, feature African dress, adornment, games, spiritual symbols, musical instruments, means of exchange, design, ivory production, and other topics, as well as three site-specific artworks created for the exhibition.

The galleries’ lead curator, Tukufu Zuberi, the Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations and a professor of sociology and Africana Studies at Penn, says that the exhibition makes explicit the debt the museum’s collection owes to colonialism. One example is a set of bronze and ivory pieces from the Benin Royal Palace, in modern-day Nigeria, looted by British soldiers in 1897. On display is a July 18, 1898, letter from the British anthropologist Henry Ling Roth to Penn Museum curator H. C. Mercer (founder of Doylestown’s Mercer Museum), offering to donate one group of Benin artifacts to Penn.

An exhibit titled “A Partial History of Africa Through Exchange” shows a variety of currencies, including gold and copper coins, cowrie shells, coral beads, and contemporary paper money. The text underlines the traffic in enslaved Africans, and the vitrine contains iron shackles from Ethiopia from the late 19th or early 20th century. Slavery continued in that country into the 1950s, Zuberi points out.

While historians note the contributions of enslaved Africans to the development of Europe and the Americas, “we rarely reflect on the impact of that enslavement on the African continent,” Zuberi says. “Many economies were degraded [and] others were elevated because of their position in enslavement. The economies of the entire African continent, from Cairo to Capetown, [were] all transformed by this demand for human bodies.”

Among the contemporary artworks in the galleries is a dress of embroidered kente cloth designed by Breanna Moore C’15 and Emerson Ruffin. Inspired in part by an intricately carved ivory box in a nearby vitrine, it was fashioned in both the US and Ghana. Marking one exhibition entrance, the Brazilian artist Jorge dos Anjos contributed two metal sculptures relating to the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé.

A husband-and-wife team—Philadelphia-born Muhsana Ali and Senegal native Amadou Kane Sy—created a map-like mosaic of colored cement ornamented with ceramics, metal cans, and other objects, as well as numbered tags suggesting the museum’s classification system. Titled Presence of a Fundamental Absence and assembled largely in the studio of Philadelphia mosaic artist Isaiah Zagar, a longtime friend, it evokes both the labors of archaeologists and the journeys of what the artists call the “lost and powerful” artifacts in the Africa Galleries.

The objects in the mosaic, from the artists’ own collections, have taken a different route. They “may have been transported from the West to Africa,” where they were “imbued with the energy of the place and the people,” Ali says. “Now, they’re being transported back to the West.”

The brown backdrop is meant to suggest the ground from which archaeologists unearth artifacts, her husband says. “It brings back those images of when they’re digging,” he says. “It’s a question of looking for something: lost and found, found and lost, like a big boomerang.”

—Julia M. Klein