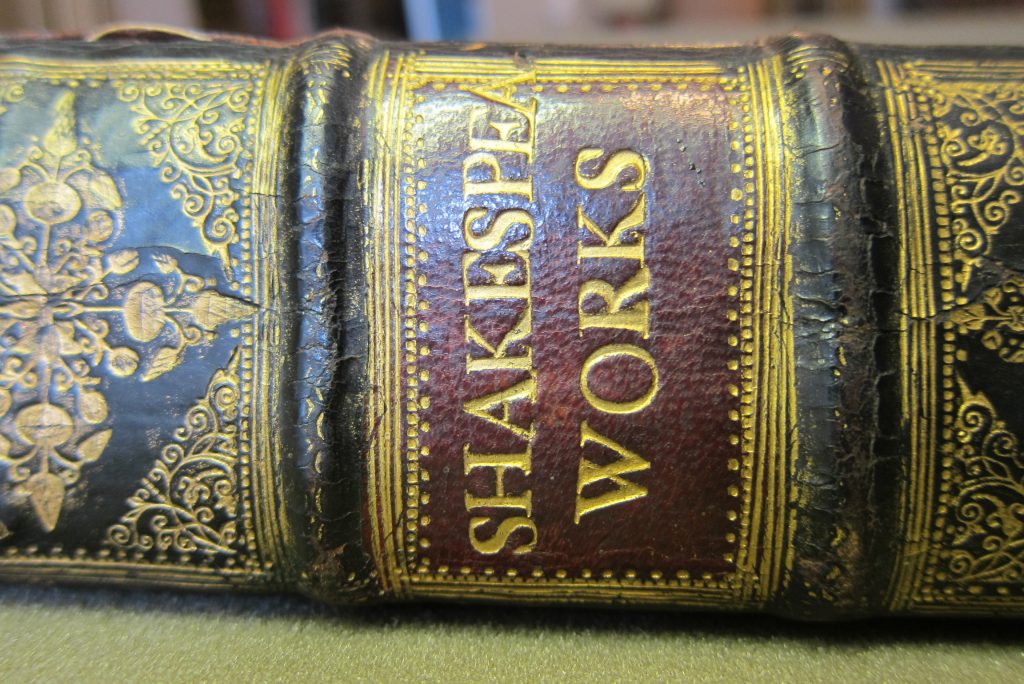

The first time Claire M.L. Bourne Gr’13 saw a copy of William Shakespeare’s First Folio—a posthumous collection of the playwright’s work published in 1623—she was inside the Free Library of Philadelphia, visiting as part of her first graduate seminar at Penn.

From that moment onward, Bourne was captivated not just by the book itself, which is one of 235 surviving copies, but also by the hand-written markings that fill the pages of that particular edition.

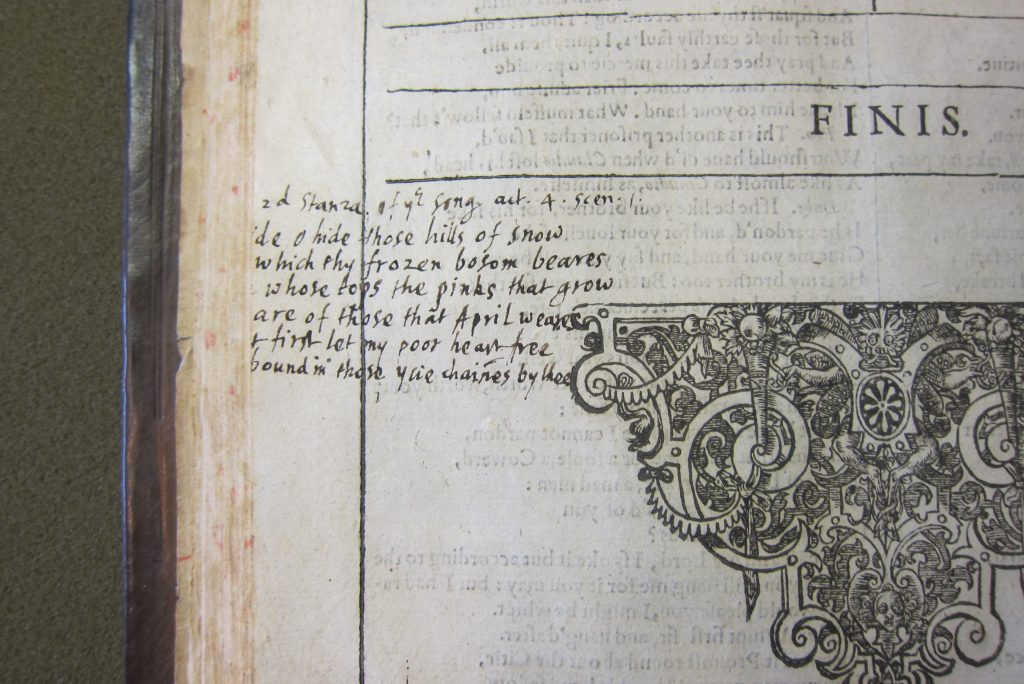

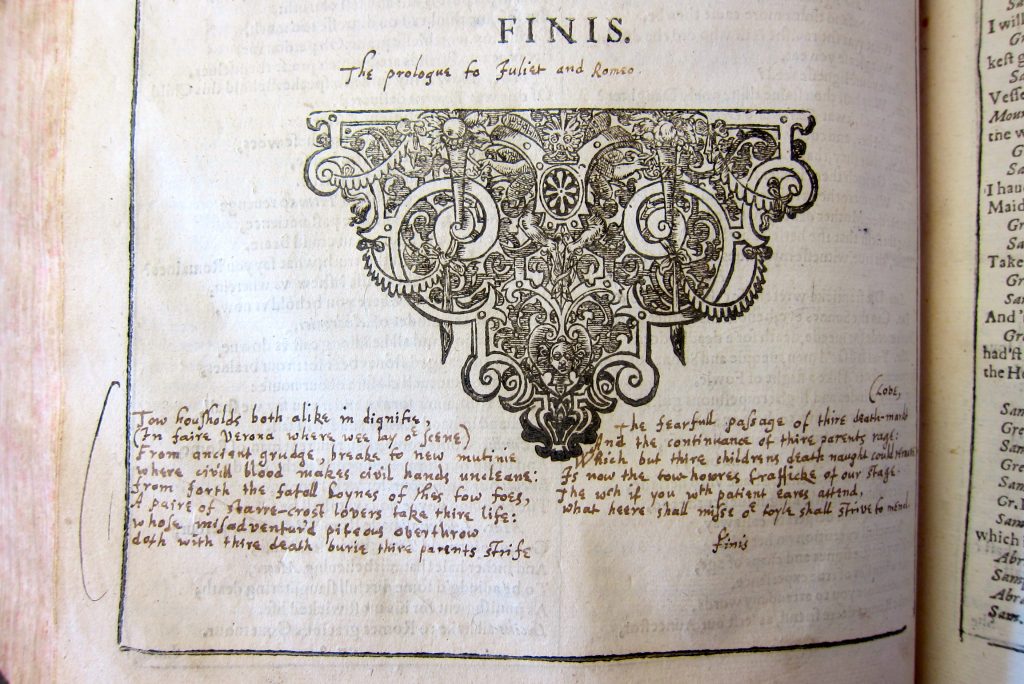

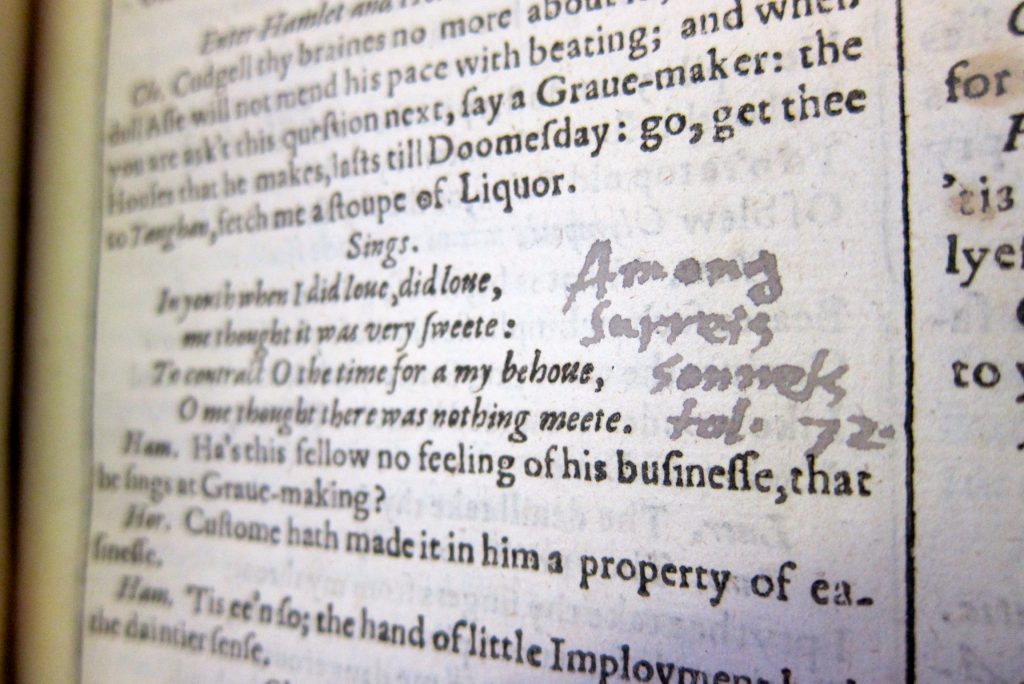

What 17th-century reader, she wondered, would have so extensively and painstakingly annotated Shakespeare’s work? What kind of person, reading Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet, would go through the text making corrections and writing in possible alternatives for certain words? And why?

“It’s rare to find an early reader of plays—Shakespeare in particular—who’s engaging with such attention to the text,” says Bourne, who is now an assistant professor of English at Penn State.

Twelve years and a series of serendipitous unfoldings later, Bourne now has a very likely answer to the mystery reader’s identity, and it’s a big reveal: the English poet John Milton, who wrote Paradise Lost.

How Bourne came to know this—and how her years of meticulous scholarship enabled the discovery—begins back at her time at Penn and that first trip to the Free Library.

After her initial encounter with the First Folio, Bourne channeled her curiosity into a short essay for her class, which was led by English professors Peter Stallybrass and Zachary Lesser. Over the next five years, she continued to tinker with that essay as a side project, slowly expanding it into a longer article while also pursuing her PhD in English at Penn.

Through her research and close examinations, Bourne realized that this First Folio reader wasn’t just jotting down suggestions based on personal preference or intuition. Rather he was taking later, single editions of Shakespeare’s plays (also known as quartos) and comparing those texts with what had been printed in the folio collection.

“The texts are slightly different in the folio and the quartos, and this reader was really interested in that variation,” Bourne says. “While the folio tries to kind of monumentalize Shakespeare, this reader was saying, implicitly, that Shakespeare is actually a corpus in flux—always shifting and changing.”

She hoped that someone would publish her analysis, but several journals turned her down—until, after five years, she finally found the right home.

In December 2018, editor Katherine Acheson published Bourne’s essay in her book Early Modern English Marginalia (Routledge, 2018). Alongside Bourne’s scholarship, the essay included over two dozen images from the Free Library’s First Folio (see above and below for examples).

Next comes the serendipity. Back in Shakespeare and Milton’s homeland, Jason Scott-Warren—a Cambridge professor who also had an essay in Acheson’s book—read Bourne’s essay and saw the photos. He knew Milton’s handwriting, and between the images and Bourne’s description of the mystery reader, “I started to wonder about it quite early on,” he says. “I thought, could that be Milton?”

“I think we’re taught to be skeptical of these kind of connections—these impulses that we’re seeing something super-important,” Bourne says. Still, when Scott-Warren sent her a message about his theory, “I thought the evidence was pretty compelling,” she says.

This past September, Scott-Warren put up a blog post titled “Milton’s Shakespeare?” and shared it widely on social media. “Things really took off from there,” Bourne remembers. “We got a lot of eyeballs on the evidence very, very quickly. Consensus started to form fairly fast around the hypothesis—especially from Miltonists, who have been working with Milton’s materials for decades and are also very familiar with his handwriting.”

The news avalanche came quickly, too, with stories in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Philadelphia Inquirer and many other outlets. People were captivated by the idea of Milton, the man widely considered England’s second-greatest poet, scrutinizing its original king of the written word.

“It’s a whole new cache of evidence, especially for Miltonists who are interested in Milton’s reading practices and how those practices informed his own writing,” Bourne says.

While Milton’s library “must have been enormous,” Scott-Warren notes, “we don’t have many books from it: about 10,” and most of them are in Latin, Greek or Italian. Now the Philadelphia Free Library’s Shakespeare folio will likely join that very short list.

Noting that the marked-up First Folio “allows you to start trying to read Shakespeare through Milton’s eyes,” Scott-Warren predicts that it’s also “going to be very interesting to see what people do with that evidence. We might end up with a rather transformed sense of young Milton.”

And even though he was the one to connect the handwriting to Milton, Scott-Warren says that “without Claire’s work, there’s no way this discovery could have been made.”

“This whole story really shows the value of the kind of slow and patient scholarship that Claire undertook on this copy of the First Folio,” notes Lesser, who was her dissertation advisor at Penn. “She worked on this out of her passion for the book—a real love for this copy. It was not the kind of thing that you could see an immediate payoff to. A lot of humanities scholarship is like that.”

He says that her debut book, set to be published this spring by Oxford University Press, is a further example of that diligence. In Typographies of Performance in Early Modern England, Bourne examines written plays from around 1512-1712, considering how typography and page design helped turn them from performance pieces into readable works. While researching, she looked through roughly 1,900 different editions of printed plays.

“That’s the kind of scholar she is: she works on things for a long time and amasses as much evidence and data as she can,” Lesser says. “Then she’s able to take that huge amount of evidence and mold it into a really interesting and powerful argument that has clear stakes for the rest of us.”

At the moment, Bourne and Scott-Warren are also collaborating on a more formal, scholarly write-up of the mounting evidence that Milton owned this particular First Folio. Bourne says they’re hoping it will be published in 2020. “This is ongoing and highly collaborative research,” she adds.

—Molly Petrilla C’06