My Journey with Paul Fussell.

By Anthony Schneider

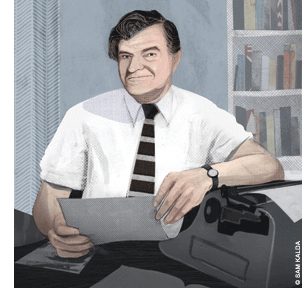

Inside Bennett Hall, past the looming Shakespeare portrait, left through the double-doors to office 112. The professor sat at his desk, sturdy manual typewriter behind him. Bookshelves and travel posters lined the walls—Cunard and Chamonix. I sat nervously, fidgeted. He talked. Briefly. His accent was clipped, and he spoke in whole sentences. He liked my idea for an undergraduate honors thesis (American travel writing between the wars), asked if I’d traveled. Yes, I said, I liked to travel, had grown up in South Africa and traveled a bit in Europe, wanted to travel more.

He whirled around and began typing. Had I said the wrong thing? I considered whether I should have worn a tie, got a haircut, prepared an eloquent statement. Tap-tap-tap, return. Tap-tap-tap, return.

Finally he whizzed the sheet out of the typewriter, spun around and thrust the page toward me. I picked it up and read the names of books. Most of them I didn’t know. Some of the authors—William Carlos Williams, Evelyn Waugh, Sinclair Lewis—I did. Baedeker Guide sat authorless and pugnacious on its own line.

“Read those, come back in a week.”

I took that to mean I’d been accepted. My heart leapt.

“Okay, great,” I replied. And mumbled a question about how I would distinguish fiction from nonfiction in my thesis.

He looked at me. “Fiction or nonfiction.” Tweed jacket, seafarer’s eyes, slightly down-turned mouth, hair parted on the side. “I can’t tell the difference, can you?”

And so began my journey with Paul Fussell, who became my thesis advisor in the fall of 1986. A Penn gem (he taught here as the Donald T. Regan Professor of English from 1983 to 1994), Fussell wrote The Great War and Modern Memory, the acclaimed cultural study of the “British experience of the Western Front from 1914 to 1918 and some of the literary means by which it has been remembered, conventionalized, and mythologized,” as the author himself put it. He also wrote a definitive treatise on poetic meter, a book about class, another about uniforms, articles about nude beaches and war films.

I was in his office that day because I was besotted with travel, with seeing the world, and because I’d read his book Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars. Like The Great War and Modern Memory, it’s one of those books that every undergrad should read. Brilliantly reasoned, well-written and innovative, it puts things together, delves, reconfigures. The book mapped context where I’d previously seen things that were unmatched and unmoored (war, travel, sex, passports, narrative, television). Fussell wrote not in the wrought, higgledy-piggledy academic language I’d become accustomed to reading with burning eyes and grinding teeth but in smooth, seductive prose, crisp as a summer suit. He was an original thinker, combative and cool, an anti-establishment snob, and a war hero. I was more than a little awestruck.

I read 12 books in a week. And returned to his office for my first real meeting. From that day on, we met just about every week, mostly in his Bennett Hall office but occasionally in a low-key restaurant near his Rittenhouse Square apartment that produced, as he promised, a good BLT and a decent gin and tonic. We drank gin and tonics and talked about D.H. Lawrence and sex, about W.C. Williams and oranges, about loss and outrage, travel and tourism, civilization and solitude, about far-flung places, about books and movies, about the virtues of grumpiness and the resonance of irony and, of course, Americans abroad. When I suggested something about how English friends spoke about travel or what I’d overheard a group of Americans saying in London, and wondered if these insights were relevant to my paper and, if so, how to insert them, he advised me to write it, just as I had described the conversations. And so I did, inserting scraps of first-person, current-day observations into my thesis.

“Gah,” he said. “Too many big words.” This upon reading my first draft. “Don’t use a big word when there’s a short word that’s just as good.”

It was probably at one of those gin-and-tonic lunches that I told him I wanted to write fiction, was writing short stories. “Just don’t write one of those thinly veiled semi-autobiographical coming-of-age novels,” he told me. There is at least one whole novel I never wrote as a result. Thank you Dr. Fussell.

After graduation I visited him a couple of times in his office in Bennett Hall. I had traveled; I had explored. A hill tribe in northern Thailand (I was the first foreigner they’d laid eyes on in 10 years), Xios, Sardinia, rural Japan. Fussell approved. We discussed an anthology I wanted to edit about exiles and immigrants. (The project never really got off the ground; nevertheless, we discussed it at length.) So many Americans are immigrants or exiles, he mused. A California boy who ended up fighting in France and teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, he was one of them. Would he consider writing the introduction? Of course.

And I continued to read his books, pencil in hand.

Fussell on civilization: “Civilization is an impulse toward order; but high civilizations are those which operate from a base of order without at the same time denying the claims of the unpredictable and even the irrational.”

Fussell on tourism: “Tourism requires that you see conventional things, and that you see them in a conventional way.”

Fussell on war: “The worst thing about war was the sitting around and wondering what you were doing morally.”

Paul Fussell died on May 23, 2012, at the age of 88. He won a Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts, a National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. He touched a great many students, shaped a great many thinkers, and inspired teachers, travelers, and writers. Thank you Dr. Fussell.

Anthony Schneider C’87 is the author of Tony Soprano on Management (Penguin, 2004), which has been published in five languages. His novel will be published next year.