Behind the new Winslow Homer exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

By Lesley Valdes

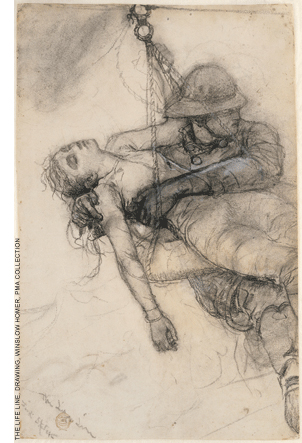

Ten years ago Kathleen Adair Foster, adjunct professor of art history, was walking past Winslow Homer’s “The Life Line” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art when she noticed “something going on around the woman’s shoulder.”

Having recently begun her new job as the museum’s Robert McNeill Jr. Curator of American Art and director of its Center for American Art, Foster was curious about what appeared to be changes to the surface of the painting, which depicts a nearly drowned woman in soaked clothing lying limply across her rescuer as both are hoisted above a turbulent ocean. So she walked over to the PMA’s conservation department.

“I needed to see if the painting had been damaged and painted over,” Foster recalls.

“The Life Line” is one of Homer’s most dramatic paintings, a late-19th-century oil whose realism suggests photojournalism, and the centerpiece of a new exhibition at the PMA titled Shipwreck! The exhibition, which opens September 22 and runs through December 16, features 30 works by Homer—oils, engravings, watercolors—including the extraordinary Gloucester, Massachusetts, schooner series from the 1880s, as well as marine works by other artists and collateral documents about wrecks and rescues from the 17th century through the 19th. (Coincidentally, the Portland Museum of Art in Maine also offers a Homer exhibition—Weatherbeaten: Winslow Homer and Maine—that opens on September 22 and runs through December 30.)

“The Life Line,” which has been in the PMA’s collection for 90 years, was a spectacular success when Homer displayed it at the National Academy for Design in New York in 1884, notes Elizabeth Johns, emeritus professor of art history and author of Winslow Homer and the Nature of Observation. The painting sold swiftly and for a higher price ($2,500) than any other work in his lifetime.

“People were intrigued with destiny and drama—who was saved, who was not,” says Johns. And there is no shortage of drama in “The Life Line.”

Conservation files bore out Foster’s suspicions: Homer had indeed made changes. The most dramatic was the addition of a red scarf, flapping in the wind and concealing the visage of the rescuer, a “surfman” in the US Life Saving Service, forerunner to the Coast Guard.

“The scarf was added at the 11th hour—after he’d already painted the surfman’s face,” says Foster, who calls the discovery “a jaw-dropper.”

By painting out the surfman’s face in “The Life Line,” Homer underscored the man’s heroism.

“He wants the woman to be the center of attention, the helpless maiden,” says Foster. “The surfman—he’s the knight with the visor down.

“We want our heroes to be anonymous,” she adds. “All superheroes have masks.” Red not only focuses the viewer’s attention; it also symbolizes passion, blood, and danger.

Homer had also scraped out and painted over one of the surfman’s hands, which had been on the woman’s shoulder.

“In the original drawing his two hands almost meet,” Foster explains, “one around her ribcage, the other around her shoulder like he’s making a ring around her. That’s the place [where] the surface of the painting looks funny.”

Curious as to why Homer took the hand out, Foster arrived at two conclusions.

“Number one, he wants a clean line,” she speculates. “Number two, [the surfman is] obviously not embracing her.” This is 1884, she notes, with its Victorian mores. “The painting is already suggestive—the way the clothes are clinging to her. He didn’t want to be inappropriate.”

To confirm what her eyes had suspected, Foster made use of Homer’s preliminary drawings, as well as infrared photography (which showed the scraped-out hand) and X-radiographs—the same techniques she would use four years later as a principal on the restoration and exhibition of Thomas Eakins’ “The Gross Clinic.”

Eakins (1844-1916) and Homer (1836-1910) were vastly different men, but as artists their realism—the truthfulness of their observations—has a distinct parallel.

“They are extremely important to the evolution of identity in late 19th-century American art,” points out Michael Leja, professor of art history. And, he adds, Foster “knows everything about Eakins.” Two years before she took the PMA post, Foster’s Rediscovering Thomas Eakins (Yale University Press, 2000) won the prestigious Eric Mitchell Award for a work of art history.

Her knowledge and passion for Eakins proved invaluable when, in 2006, Jefferson University Medical College agreed to sell “The Gross Clinic,” a move that would have devastated Philadelphia’s art community and self-image. Foster, an authority on Philadelphia’s own master, went into high gear with her boss, the late Anne d’Harnoncourt, and their efforts were ultimately successful in keeping the masterpiece in town.

“People are hungry for art history,” she says she realized. “The public loves these conservation tales: it gets them backstage.”

While she had originally envisioned the Homer exhibition as relatively modest in scope, Foster says, “the tremendous response to ‘The Gross Clinic’ encouraged me to build Shipwreck! out.”

There is another backstory in “The Life Line,” which depicted an important new lifesaving device: the breeches buoy. The buoy was “basically a cork ring to which trousers—breeches—are sewn,” explains Foster. But since getting into them, for a woman, meant lifting her skirts, some refused to use them. Homer painted the woman in “The Life Line” as lying across the breeches, not in them.

Getting the buoy from land to the distressed ship was no small task, either. As a Coast Guard demonstration video shows, the line with the buoy was shot from a cannon on land to the ship.

“Before the invention of the buoy, women and children were most at risk,” Foster notes. If the wreck occurred too far from shore, “they wouldn’t have the strength or stamina to hold on to a rope, going hand-over-hand in freezing water.”

Foster believes “The Life Line” was a shot in the arm for the Life Saving Service, which had been struggling to train and employ personnel along the graveyards of the Atlantic since 1871. One section of Shipwreck! focuses on the rise and reform of the Life Saving Service; another traces the glory and peril of ocean travel.

Homer spent the last 27 years of his life painting in his studio overlooking the ocean at Prouts Neck, Maine, 12 miles south of Portland. He probably completed “The Life Line” there; in Foster’s opinion “the water looks like Maine.” For all its obvious connections with that rugged coast, though, “The Life Line” was actually conceived in Atlantic City.

At the time, the Life Saving Service was doing test runs of the breeches-buoy equipment. There were brigade houses up and down the Jersey shore, and Foster suggests that Homer “probably got some [Life Saving Service] friends to take him” with them as they tried out the equipment. After watching and presumably sketching what he saw, Homer went back to his Tenth Street studio in Manhattan and painted models, “dripping them down with water to get the effect.”

“The Life Line” was one of the first of an important rescue series (1883-1889) in which humans are pitted against the sea. Two years after completing it, he painted “Undertow.”

Whether by chance or planning, Homer’s vision was changed by his experience in the English fishing village of Cullercoats, on the North Sea, where he lived for 20 months in 1881-1882. There he observed the English Life Boats, a lifesaving service that was considerably more advanced than its US counterpart.

The conditions were harsh in the coastal village, and while Homer had always painted women with great sensitivity, he gained more observing Cullercoats’s stoic fisherwomen. “There’s a whole trove of letters he wrote about these magnificent women,” says Johns, who refers to them in her book.

By 1890, Homer was living year-round in his Prouts Neck cottage, 75 feet from the ocean. In “Winter Coast,” which he completed that year, nature and the elements had moved to the foreground. Nature triumphs; man recedes.

Lesley Valdes is a freelance writer and art critic.