“Convicted felons, divorced parents who fail to pay child support, people with a record of domestic violence or emotional abuse, delinquent taxpayers, drug abusers, rapists, murderers, racists, anti-Semites, other bigots: all can marry if they choose,” said philosopher Martha Nussbaum. “And indeed have been held to have a fundamental Constitutional right to do so—as long as they want to marry someone of the opposite sex.”

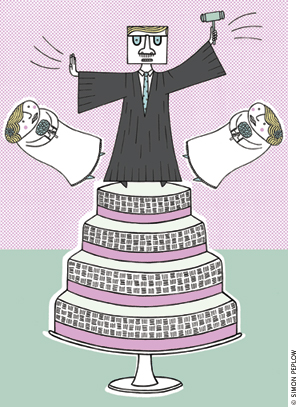

Nussbaum came to campus in March riding a wave of acclaim for her most recent book, From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law, which has been lauded as a meticulous and dispassionate exploration of an issue that more typically prompts vitriolic outbursts or politically correct bromides, depending on which cable-news squawk-a-thon you tune into. Currently a professor of law and ethics at the University of Chicago, Nussbaum is a political theorist whose career has been marked by an insistence that the practice of philosophy should count the transformation of public life among its primary aims. Her emphasis on the primacy of individual rights over state control and cultural restraints is rooted in the tradition of John Stuart Mill. In her 2010 Levin Family Dean’s Forum lecture she focused that doctrine on the question of same-sex marriage. Does government serve a compelling public interest by denying to gay citizens a “civil benefit and expressive dignity” it extends to all others—right up to those on death row?

In the last half-century U.S. courts have stricken down many laws that thwarted an individual’s ability to enter marriage. Indeed there have been rulings upholding the right to marry even among citizens who have forfeited, through criminal behavior, such cornerstone liberties as the right to vote. Yet the right to marry has not been deemed inalienable. The public interest is often invoked by states that wish to restrict it. For example, states that offer marriage are not required to sanctify polygamous unions. “The primary state interest that’s strong enough to justify [this] legal restriction is an interest in women’s equality,” Nussbaum noted. “Regulations on incestuous unions have also typically been thought to be reasonable exercises of state power,” she added, observing that “the interest in preventing child abuse would justify, in most cases, a ban on parent-child incest.”

The usual arguments for barring individuals from entering into same-sex marriage, in Nussbaum’s view, stand on flimsier footing. “The first and most widespread objection against same-sex marriage is that it’s immoral and unnatural,” she said. In an earlier era, this was a popular justification for anti-miscegenation laws that barred individuals from marrying someone of a different race. It bears a close resemblance to another argument—that state approval of a practice many citizens consider evil forces them to bless it, thus violating their conscience. The essentially religious character of both objections, Nussbaum observed, makes them difficult to defend without running afoul of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, especially since different denominations vary considerably in their views about same-sex marriage. A state that embraced these objections would be siding with one group of believers against another.

Another common claim raised by opponents of same-sex marriage is that the state’s primary interest in sanctifying marriage is to foster procreation and childrearing. Yet states routinely issue marriage licenses to couples who are unable or unwilling to have or raise children. Since the procreation argument is rarely marshaled in support of a ban on, say, octogenarian marriages, it “looks two-faced,” Nussbaum observed, “approving in heterosexuals what it refuses to tolerate in same-sex couples.”

Does the state’s public interest in “protecting” children justify a prohibition on same-sex marriage? Not according to the factual evidence, Nussbaum contended. “Again and again, psychological studies have shown that children do better when they have love and support, and it appears that two-parent households do better at that job than single-parent households,” she said. “There’s absolutely no evidence, however, that opposite-sex couples do better than same-sex couples.”

What about the notion that same-sex marriage represents a threat to traditional marriage, and that a ban on the former would buttress the latter? Nussbaum defended the interest of states to help traditional marriage, but expressed skepticism over the means. She suggested that the stresses facing traditional marriage might be alleviated by a wide range of public policies—family and medical leave, tighter enforcement of child-support laws, increased availability of drug and alcohol counseling, etcetera—but that same-sex unions have little bearing. “If we were to study heterosexual divorce, we would be unlikely to find even one case in which the parties expressed the view that their divorce was caused by the availability of marriage to same-sex couples,” she said. “Divorce is usually an intimate personal matter.”

But even if the availability of same-sex marriage is unlikely to break the bonds of heterosexual couples down the street, might the recognition of same-sex unions as being on a par with traditional marriage demean the very institution, diminishing its value for those who have pledged their bond as man and wife? This is also a common claim among opponents of same-sex marriage, and it brought Nussbaum to the heart of her analysis.

This formulation, she observed, strikes a similar logic to that expressed by baseball fans who worried that the admission of players who had used performance-enhancing drugs into the Hall of Fame would cheapen and undermine the achievements of athletes who had played by the book. “In general the point seems to be that the promiscuous recognition of low-level or non-serious contenders for an honor sullies that honor,” she said. “How should we respond?

“I’ve never heard anyone say that the state’s willingness to marry Britney Spears or O.J. Simpson demeans or sullies their own heterosexual marriage,” she answered. “But somehow, without knowing anything at all about the character or intentions of the same-sex couple next door, they do say that their own marriages would be sullied by the recognition of that union. If the proposal really were to restrict marriage to worthy people who have passed a character test, it would at least be consistent—though few would support such an intrusive regime. What’s clear is that those who make this argument don’t fret about the way unworthy or immoral heterosexuals might sully the institution of marriage or lower its value. Given that they don’t worry about this, and given that they don’t want to allow marriage to gays and lesbians who have demonstrated their high moral character, it’s hard to take this argument at face value.”

What lies beneath the argument, she asserted, is something that is both more deeply felt and harder to defend, at least on Constitutional grounds: disgust.

“The only distinction between those unworthy heterosexuals and the whole class of gays and lesbians that can possibly explain the difference in people’s reaction is that the sex acts of the former do not disgust the majority whereas the sex acts of the latter do.”

Disgust has its defenders. It is a part of our evolutionary heritage; we have the emotion of disgust to thank for our aversion to rotting carcasses, for instance. Some have argued that the “wisdom of repugnance” is a sound rationale for laws limiting or forbidding things like genetic engineering, abortion—and same-sex marriage. Nussbaum, suffice it to say, is not one of them. She argued that repugnance provides a poor foundation for good lawmaking, or more precisely, a strong foundation for poor lawmaking.

“If we’re looking for a historical parallel to those anxieties, we can find it in the history of views about miscegenation. At the time of Loving [v. Virginia, in 1967], 16 states both prohibited and punished marriages across racial lines. And the arguments appealed very overtly to disgust. For example in the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 in Virginia, which invokes an idea of racial purity and a corresponding idea of taint or defilement,” she said. “If people felt disgusted and contaminated by the thought that an African American had drunk from the same public drinking fountain, or gone swimming in the same public swimming pool, or used the same toilet, or the same drinking glass,” Nussbaum added, “you can see that the thought of sex and marriage between blacks and whites would have carried a powerful freight of revulsion.”

Nussbaum ventured that the revulsion that undergirds opposition to same-sex marriage today is no different—and no more legitimate than the Supreme Court found it to be when it overturned Virginia’s anti-miscegenation statute in Loving. “I think the thought must be that to associate traditional marriage with those sex acts, that are so disgusting, is to defile or contaminate it,” she said, “in much the same way that eating food that was served by a Dalit used to be taken by many people in India to contaminate the high-caste body. Nothing short of a primitive idea of stigma and taint can explain the widespread feeling that same-sex marriage defiles or contaminates straight marriage while marriages of immoral and sinful heterosexuals do not.”

—T.P.