Mother and daughter, Ghana.

Harvey Finkle SW’61 and the photography of social justice.

By Trey Popp | Photography by Harvey Finkle

Download a PDF of this article

On Mother’s Day 2021, a year after macular degeneration forced him to call an end to half a century of documentary photography and photojournalism, Harvey Finkle SW’61 made a rare Facebook post. Turning a critical eye on the ubiquitous exhortations to buy chocolates and flowers—as though those and a Hallmark card could possibly convey real appreciation for “the incredible effort it takes to mother”—he offered a different kind of tribute. Eighteen images, mostly black-and-white, depicted women nurturing young children. Finkle showed them playing together on beaches and nestled together in rest, but also seeking safe quarter as refugees, confronting challenges in wheelchairs, demonstrating for affordable housing, and marching against “the war on the poor.”

“They were so beautiful and so real,” recalls Jessie Burns. “And having been a mother, they spoke to me.”

Burns, who founded Tursulowe Press to publish “under-told stories” and “under-read classics,” had known Finkle since her earliest childhood. He’d been a close friend of her father, C. K. Williams C’59, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2000. They both lived in Philadelphia’s Queen Village neighborhood. Finkle was forever walking the city’s streets with his Leica, and over the decades became a constant presence at demonstrations for social justice causes. “Any time I went to a protest,” Burns remembers, “he was there with his camera, until he was 80-something.” Finkle worked with Project Home on behalf of unhoused Philadelphians, documented disability rights advocates affiliated with the Independent Living Movement, bore witness to death penalty activism, shined a light on child poverty in America [“Urban Nomads: A Poor People’s Movement,” February 1997], and took his last photographs in 2020 in connection with the clergy-driven New Sanctuary Movement for immigrant justice.

“He’s so much more than just a photographer,” says Burns. “He has a master’s in social work, and he’s always cared about social justice. But not a lot of people are able to go to places where people are being triumphant in their struggle and capture it. And he does.”

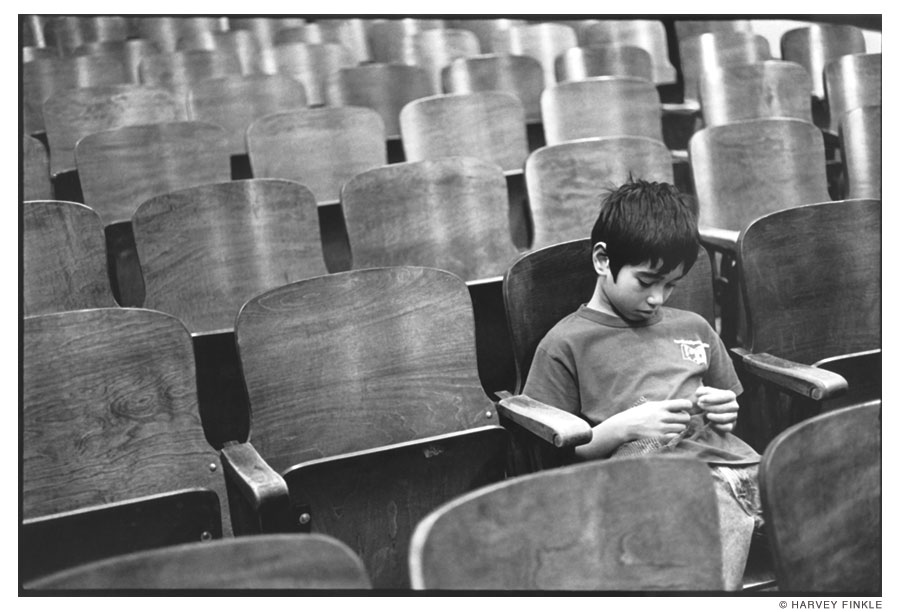

So after taking in his Facebook post, she picked up the phone and proposed a book that quickly morphed into a series that’s shaping up to be a career retrospective. In 2022 they released Mothers, followed by Under One Sky, which showcased 78 portraits of immigrant families and communities in Philadelphia. The next year they crafted a subtle response to the book-banning fervor then sweeping through school districts and libraries: Readers, whose thoroughly nonpolitical depictions of men, women, and children engrossed by books and broadsheets in all manner of public spaces—from Jerusalem and Paris to Philly street corners and SEPTA stations—are at once a time capsule of life before smartphones and a testimony to the intimacy and universality of the act of reading. Next in line is a planned volume devoted to visual patterns in urban settings and architecture, and Finkle is keen to follow that up with an installment focusing on Deaf culture. (Both of his children are deaf.) Having taken pictures of Philadelphia’s iconic Mummers nearly every New Year’s Day since 1973, he’s also eager to collect his favorites into a themed book on that inimitable South Philly subculture. In the meantime, visitors to Penn Libraries can access the full sweep of his photographic career; Finkle donated his archives to the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts in 2020.

Mother and daughter, Philadelphia.

American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today (ADAPT) rally at Department of Housing and Urban Development, Washington, DC.

Harvey Finkle was born in 1934 and grew up in Northeast Philadelphia’s Oxford Circle section, where real estate developers began planting new houses on old farms just before World War II. The Finkle family lived on a block that ended in orchards. “There were plum trees, peaches, flower farms,” he recalls. “It was like living in the country while living in the city.” His dad owned and operated an auto graveyard, where Harvey worked on and off as a teenager while attending Central High School. After graduating he enrolled at Temple University, but discovered that the classroom was no match for the city’s jazz scene, where $1 bought entry into the Blue Note at 15th Street and Ridge Avenue to hear the likes of Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie, and Billie Holiday. He lasted three semesters at Temple before dropping out and enlisting in the Army.

In 1953 Finkle underwent basic training at Maryland’s Aberdeen Proving Ground. Then he shipped out to France, where he served for 15 months. Though he felt rudderless upon his return, he reenrolled at Temple. His second try went better than his first. “I guess I could bear it,” he says. “But I still had no idea what I wanted to do.”

His first glimmer came after graduation, when he heard that the Philadelphia County Board of Assistance was hiring people with college diplomas to help administer public welfare programs. He spent a year and a half helping “desperate people in need” obtain housing and other assistance. The experience moved him to pursue a master’s degree at Penn’s School of Social Work (the predecessor to today’s School of Social Policy & Practice). There, an academic field placement with the Pennsylvania Society to Protect Children from Cruelty—which led to further involvement after he completed his degree—proved deeply influential.

“You were going out to visit people who don’t want you to come into their home,” he reflects, “and saying, ‘Hey, we have a report that suggests you’re having a problem with your children.’ People knew that there was a possibility of losing their kids,” and they knew that a court proceeding could bust their families apart. “That was not our ambition,” Finkle says. “Our ambition was trying to help them remedy whatever the problem was, and then help them keep their kids.” Nevertheless, a knock on the door from his agency was the last thing a struggling parent wanted to hear.

His social work training taught him one thing above all others: “The instrument is yourself,” as Finkle puts it. “It’s understanding yourself in order to understand and identify with the person you’re going to be working with, and how you might help them.” He was drawn to that challenge, and invigorated by the exercise of empathy and patience it required. The delicate work of building rapport and trust would also become indispensable to his photography.

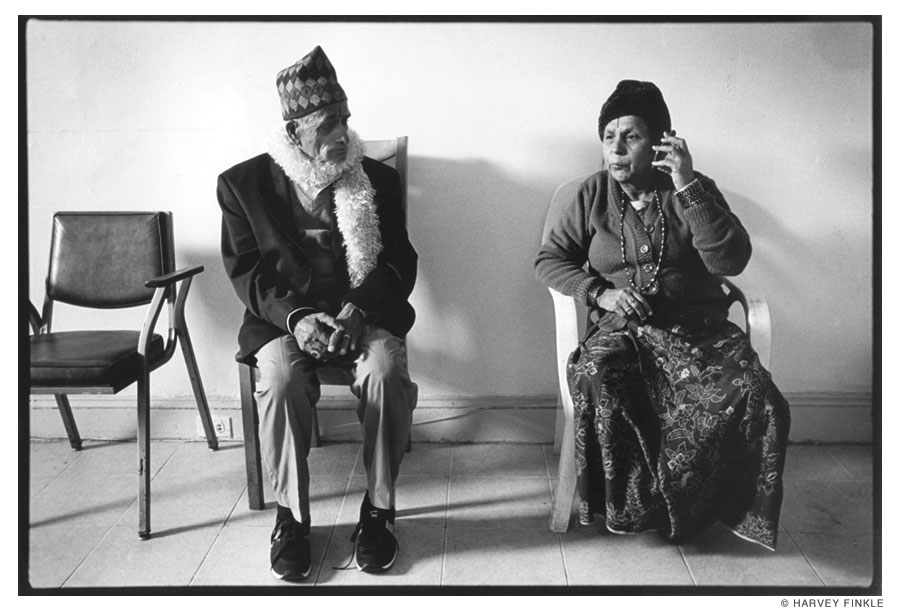

First day in their apartment for refugees from Nepal (Philadelphia, 2012).

Immigrant factory worker (Philadelphia, 1992).

In the mid-1960s Finkle worked for an experimental preschool program that was a forerunner to Head Start, and then became a field representative responsible for setting up county-level programs under the Older Americans Act of 1965, part of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society initiative to provide comprehensive services for senior citizens, ranging from housing and healthcare, to employment-related support, to civic and cultural engagement. Then, in 1968, he became a parent—and bought a camera. Turning it first on his son, then a daughter who followed two years later, Finkle became a dutiful documentarian of family life.

The hobby swiftly invaded virtually every facet of his life—especially once he found equipment that clicked with his instinct for fading into the background. His first model, a Mamiya single-lens reflex, “didn’t really work right for me.” Then he bought a Leica, which was blissfully free of a noisily flapping mirror. That made all the difference. “It’s small, it’s black, it’s quiet,” Finkle explains. “I could focus it pretty quickly. It’s unobtrusive. I could walk into crowds of people and take pictures.”

Young Ethiopians (Philadelphia, 2022).

Boy from Burma in school auditorium (Philadelphia, 2017).

In his off-hours he would wander through Philadelphia. “I liked to walk the streets and shoot in the streets.” Meanwhile he became involved with a grassroots association called the People’s Fund, which was founded in 1971 by a group of activists seeking to spur liberal social change by funding organizations like the National Lawyers Guild and Women United for Abortion Rights. Finkle likened it to the United Way—only for causes that the actual United Way was loathe to touch. (As cofounder Rick Baron has stated elsewhere, “When we started off, we were explicitly not tax-exempt because we wanted to be clear that the money was political.”)

The People’s Fund, which survives today as Bread & Roses, raised about $12,000 its first year and made grants to 10 groups. “And I was the only one with a camera,” Finkle says. “So I began photographing what we did.”

It felt like a natural extension of his social work—forging connections, building trust, working with purpose—only with a captivating technical dimension. “I liked the idea of dealing with groups involved in social change, and political change, economic change,” he says. “I liked feeling like I was doing something worthwhile. And I liked taking the pictures. I liked coming back, developing the film. Making prints in the beginning was like magic, seeing an image come up in the developer.”

Taking early inspiration from the American photographer Harry Callahan (1912–1999), Finkle invested an increasing degree of artistry and sophistication into his work. In 1972 he transitioned to photography full time. He shot for labor unions, social agencies, nonprofits, hospital publications, the Philadelphia Public School Network, and the like—supplementing his mission-driven work with the occasional wedding.

Street photography remained a core part of his practice, and he became particularly adept at portraiture of immigrants. A 1977 project found him interviewing and photographing Holocaust survivors who’d settled in Philadelphia. Their diversity and perseverance impressed him. “There was the head of a union, a person who made artificial limbs, an opera singer,” he has reflected elsewhere. “They talked to me about resilience and overcoming their past to build positive, successful lives.” His 2001 volume Still Home: The Jews of South Philadelphia is a touchstone of that work, which continued with a grant to document communities of Hmong, Lao, Cambodian, and ethnic Chinese people from Vietnam who had resettled in South Philadelphia. Many of those images appear in Tursulowe Press’s Under One Sky retrospective. Although Finkle’s portfolio expanded to documentary travel photography beginning with a 1977 trip to Cuba, the city of Philadelphia remained his abiding subject—and above all, Philadelphians fighting for change.

Readers in Philadelphia.

Social change has never been easy to achieve, in Philadelphia or anywhere else. Resistance is strong and every victory is vulnerable to reversal. Documenting those struggles can be a dispiriting task. Yet Finkle looks back at his own modest part in them with satisfaction. “There are moments when you’re down, but I don’t think I stay there,” he says. “I felt I was productive, I guess—as one element in groups of people.”

Perhaps his greatest sense of accomplishment stems from his long involvement with the disability rights movement, which he began documenting in 1984. As an ally of the pioneering disability rights attorney Stephen F. Gold, Finkle became a fixture at protests and civil disobedience actions targeting noncompliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA).

Frustrated by the poorly maintained and perennially malfunctioning wheelchair lifts on SEPTA buses, disabled activists would handcuff themselves to buses. Vexed by constantly out-of-service elevators at underground stations, protestors would straddle the platforms and subway cars with their wheelchairs at rush hour. Finkle would record the scenes. “They’d put themselves halfway on the train so it couldn’t move—and they did it at four o’clock in the afternoon,” he recalls. “Other people would say, ‘I can’t get home!’ And they’d say, ‘Now you know how we feel!’” Once, after a group of wheelchair-bound activists had been arrested and hauled into an elevator to be taken to the police precinct, the elevator broke down on their way to be booked and charged.

Yet they ultimately prevailed in their cause. Judges decreed the installation and maintenance of elevators at SEPTA stations. And Gold successfully sued the administration of Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell C’65 Hon’00 to force the installation of ADA-compliant curb cuts on city sidewalks, which Rendell had opposed as an unfunded mandate that would cost hundreds of millions of dollars that the city didn’t have. “But they did it,” Finkle says.

He regards his involvement with the death penalty abolition movement in much the same way. “I’d take pictures in jail,” he says. “I went out and photographed individuals who had been exonerated. When I began it, a liberal friend of mine—a smart guy—said, ‘What are you doing that for? It’s never going to change.’” But 11 states have abolished capital punishment since the turn of the century, and Pennsylvania hasn’t executed a prisoner since 1999.

“So I see good things that have happened,” Finkle emphasizes. The same goes for an issue that hits especially close to home. “Take deafness,” he says. “Both of my kids are deaf. When you look at what the world was like before they went to high school, and you see what it’s like now, it’s incredible. Jimmy Carter began to have speeches interpreted [in American Sign Language] on television. The NFL still screws up all the time—they don’t show the person signing the national anthem—but there’s been improvements in all kinds of places. Deaf people can require the presence of an interpreter for doctor appointments. So they have entitlements under the law—plus advances in technology. My son just sets up his cell phone and begins signing to the person on the other end of the line.”

Indeed, that’s the sentiment that gets to the heart of Finkle’s photography. It flows from the recognition that the political and the personal are forever bleeding into one another. Politics come to bear on everyone’s life, in one way or another. And at every point of contact is a human being striving to live with dignity.

“Most of the stuff I’ve done has been related to political issues—there’s always a politics involved in something,” Finkle muses. “But a lot of my work is not political,” he adds. His images ultimately depict men and women and children as individuals whose circumstances may be unfamiliar and discomfiting, but whose desires and hopes are deeply recognizable.

Reader in Tucson, Arizona.

Reader in Philadelphia.

A collection of Harvey Finkle’s photography is currently on view at The Woodmere Art Museum:

The Art & Photography of Harvey Finkle

August 3, 2024–January 5, 2025

Opening Reception

Saturday, September 14 | 1-4 p.m.

Woodmere Art Museum

9201 Germantown Avenue

Philadelphia, PA 19118

215-247-0476

Hours

Wednesday−Friday | 10am – 5pm

Saturday | 10am – 6pm

Sunday | 10am – 5pm