The 1940 excavation.

The Coclé, who flourished from 750-1000 CE in present-day Panama, are not exactly an undiscovered people. “Most of the world’s major museums have objects from this culture,” says Clark Erickson, professor of anthropology. “But not much is understood about those objects—they’re valued more for their aesthetics.”

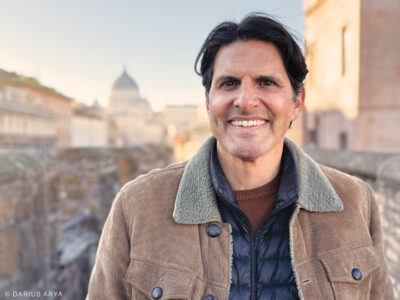

Erickson is the lead curator of Beneath the Surface: Life, Death, and Gold in Ancient Panama, a new exhibition at the Penn Museum that aims to illuminate the social reality of a civilization whose dazzling gold artifacts have long overshadowed the men and women who made them. It runs through November 1.

The Museum’s own trove of Coclé artifacts came from a 1940 excavation of a Pre-Columbian necropolis in Panama led by then-assistant curator J. Alden Mason—who never produced a monograph on his findings. Even a traveling exhibition organized by the Museum in 2008 emphasized the artistry of the spectacular horde of gold pieces, Erickson points out. “But was a certain piece used as a necklace … or a belt? Was it worn by a man … or a woman?”

Emerald pendant.

This time around, Erickson, curator-in-charge of the Museum’s American section, dove into the collection with three undergraduates, looking for answers.

“We’ve used the objects as a way to get to the people,” he says. More than 200 works are on hand, including a necklace made of dog teeth, an emerald pendant in the form of a jaguar, and polychromatic ceramic jars. The exhibition also includes a few textiles, called mola, which are used as decorative blouse panels by the Kuna, an indigenous people who live near the site today.

Because Mason’s team didn’t publish a proper academic synthesis, it’s up to today’s stewards to interpret and assemble the piles of notes, diagrams, photographs, and maps—and hundreds of pot sherds—they left behind. Penn students Sarah Parkinson C’17, Ashley Terry C’16, and Monica Fenton C’15 undertook a lot of the legwork to try to figure out how, and by whom, the jewelry and objects were used.

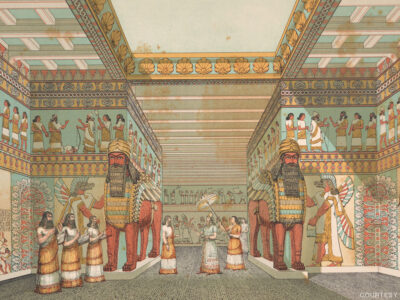

Drawing of Burial 11, Sitio Conte.

“Fortunately, Mason’s associate Robert Merrill took precise notes, had legible handwriting, and drew really detailed maps,” says Fenton, a senior majoring in anthropology. As she combed through the records associated with each piece, she was able to form a picture of where they were found in the gravesite and, consequently, to better infer the relative status of its occupants. But her work also raised new questions.

“Two of the bodies in the main burial site wore equal amounts of gold,” she says. “This opens up a possibility for further research: might there have been a pair of chiefs rather than one?”

The exhibition, though, begins with a depiction of just one man—whom the curators have dubbed the “Paramount Chief”—bedecked in gold, gold, and more gold (plaques, cuffs, belt, nose ring, headpiece). Behind this figure is a re-creation of a three-tiered burial plot known as Burial 11, which contained 23 bodies in total and yielded the richest cache. Pieces on display include gold ear rods, ceramic vessels, and stone pendants, positioned in the same manner as when they were discovered.

While the Coclé are known for their adept and innovative goldsmithing—they mastered a variety of techniques like hammering, embossing, and filigree—researchers are curious about the other media and materials they used.

“The agate figurines found in the upper level, for instance, could have been harder to work with than thin sheets of gold,” Erickson points out. “Might they have an energetic value rather than a monetary one, and does that mean the men they are associated with were particularly important?”

Elsewhere, vitrines of jars and vessels—in the cream, russet, and brown colors favored by the culture—are shaped into animal effigies, a dominant Coclé motif.

“This is one of my absolute favorites,” says Fenton, walking over to a small pitcher in the form of a quirky and most expressive frog.

Her excitement seems to have been shared by everyone who’s come into contact with the mysterious culture and its buried booty. In placing a focus on people, the curators have attempted to bring us into not only the world of the Coclé but also that of the original archaeologists, as well as those currently working at and near Sitio Conte, a five-acre site about 100 miles southwest of Panama City. We encounter the campsite of Mason and his team through vignettes featuring field notes, medicines, and equipment (such as a typewriter and camera), while rare film footage of the digs runs nearby. Along the perimeter of the gallery, touch-screen kiosks feature videos of the personalities—including Erickson, co-curator Lucy Fowler Williams CGS’01 Gr’08, and exhibition conservator Julia Lawson—who have worked to unpack (literally and figuratively) the treasures.

Much as the shattered pieces of a 1,000-year-old ceramic frog can come together and speak volumes, the disparate elements of the exhibit merge to form a more complete picture of the Coclé.

“When we think of ancient Latin America cultures, we think of the Incans, the Aztecs, and the Mayans,” Erickson says. “It’s one of the great archaeological sins that the Coclé were forgotten. With this exhibit, we want to rectify that.”