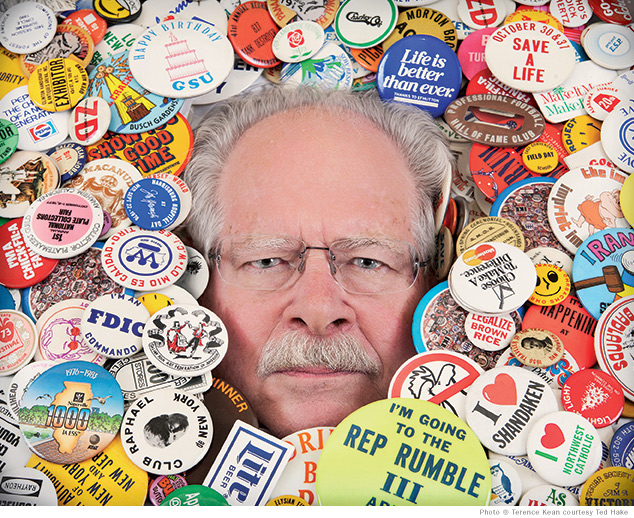

The founder of a 55-year-old pop culture collectibles auction house has “seen a treasure trove of merchandise.”

It all started with pennies. In the early 1950s, when Ted Hake ASC’69 was seven, his father suggested he start collecting pennies, figuring it’d be a good activity for an enterprising elementary schooler. So Hake’s dad bought him a pile of little blue booklets from a coin shop that had slots to put pennies in according to their dates, and he and other family members started pulling out their change and putting it in bowls for Hake to sort.

As a seven-year-old, “I was aware enough of what money was to know that this was probably going to be a good thing,” Hake, now 78, says with a laugh. “Then one thing led to another, and I became a collector.”

In 1967, Hake founded Hake’s Americana and Collectibles, now called Hake’s Auctions, which bills itself as the first auction house in the US to specialize in 20th-century pop culture artifacts. Hake sold the company in 2004 but continues to work for it as a consultant. And this year, 55 years after its founding, sales are booming.

In March, the online auction house sold two rare collectibles for record-breaking amounts. Bidders paid $185,850 for a highly sought-after 1920 presidential campaign button featuring James Cox and his running mate, an up-and-coming politician named Franklin D. Roosevelt, and $204,435 for a 1979 Star Wars Boba Fett prototype action figure.

While such high prices may seem hard to fathom to a noncollector, Hake understands it. “I think collecting is, for an individual, something that generally comes from either personal memories, or some vision they have of actual history, or some innate artistic sensibility,” he says. “I think those are the three things that really inspire people to go after things and, if they have the means, it’s whatever is most important. So there are no limits on that.”

By the time Hake reached high school, he switched from collecting pennies to “Standing Liberty” quarters, which were first minted in 1916, before getting hooked on collecting hard-to-find political buttons. While attending the University of Pittsburgh, Hake made money buying coins at wholesale prices from a coin dealer in York, Pennsylvania, (where he grew up) and reselling them for more to a Pittsburgh dealer. He did the same thing with political buttons while working at a summer job in New York—buying in York and selling in Manhattan.

Hake had an epiphany as he watched a collectibles dealer sell political buttons to lawyers, stockbrokers, and advertising executives for more than double the amount of money he had just paid Hake for them. “I remember leaving the store and standing on the step outside thinking to myself, Am I going to be a wholesaler or am I going to be a retailer?”

Choosing the latter, Hake got to work contacting fellow members of the American Political Items Collectors (APIC) with a political button inventory list. Along the way, he made mental notes about which buttons were scarce and which weren’t. At the same time, he finished his first year of New York University’s graduate film school program and decided he didn’t want to be a filmmaker. But he had to either stay in school or face being drafted for the Vietnam War, so he enrolled in Penn’s Annenberg School for Communication to pursue a master’s degree. In Philadelphia, he reestablished his political button business and, with the help of the recently invented photocopier, mailed his sales lists around the country.

Hake got the idea to hold auctions via telephone after West Coast customers complained about missing out on coveted buttons because they didn’t receive his sales list until four days after customers on the East Coast. At first, the auction business consisted of just Hake and a phone in his Philadelphia apartment.

By the late ’70s, Hake had moved back to York, where he had an office and four telephone lines for auctions, which “would run for about three weeks and people would send in mail bids,” he says. “But then on the last day of the auction—we called it closing day—you could call up, check the bids, and change them if you wanted to.” Over time, demand grew to the point that people had to wait their turn for their calls to go through.

The internet and customized software revolutionized his auction business in the mid-1980s, handling the bid-taking process for thousands of items. However, Hake’s two-day auctions still ended up being a battleground between East Coast and West Coast customers, with a lot of “sneaky” outbidding going on when people were asleep on the other side of the country. “It really got out of hand,” Hake says.

Today, the online auction puts a 20-minute timer on each item at 9 p.m. EST and if no one bids on the item, the sale is closed. If someone does submit a bid, another 20-minute timer is imposed and bidding continues. “We’ve regained control of the situation, but it took a lot of years to do it,” Hake says with a chuckle.

Hake doesn’t regret moving to the retail side of collecting. “If I had remained a collector, I could have only collected about 5 percent of what has now gone through my hands over 65 years,” he says. “I have seen a treasure trove of merchandise and hundreds of [collectible] fields that I never would have known even existed had I been limited to whatever my budget would have been.”

Asked about notable items sold by the auction house over the years, Hake cites a diverse list including four-foot-tall Mickey and Minnie Mouse dolls that were displayed in theater lobbies in the 1930s that sold for $151,534; a 1915 Boston Red Sox World Series championship button featuring a photo of the team, including a young Babe Ruth, for $70,092; and a parade banner for a group called the Wide Awakes that campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in 1860 for $143,105.

Hake’s Americana and Collectibles became Hake’s Auctions in 2018. The business maintains offices and a warehouse in York and currently holds online auctions of collectibles in a host of categories, including action figures, baseball cards and other sports memorabilia, comic books, political buttons, and toys. Hake believes video games are poised to become the next hot collectible for those who love to play the games or those looking for a good investment.

Despite being drawn to collecting coins as a child and later by the money he could make as a retailer, Hake’s personal collection strategy ultimately hasn’t wavered. “To each their own, but I would never tell anybody to buy something as an investment,” he says. “I say buy something because you like it.”

—Samantha Drake CGS’06