The son of a World War II fighter pilot probes his father’s service and its ramifications.

By Julia M. Klein

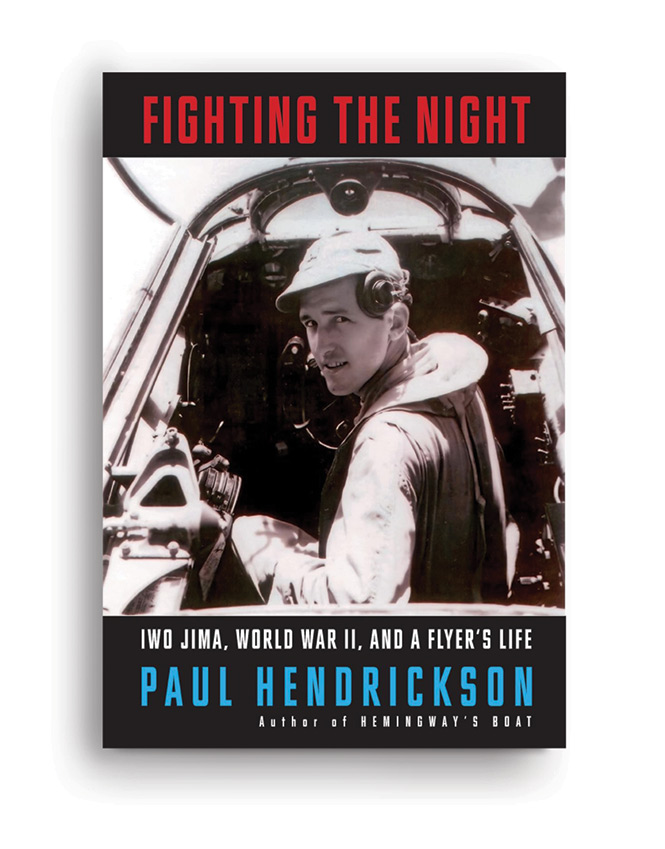

By Paul Hendrickson

Alfred A. Knopf, 320 pages, $32.

It has taken Paul Hendrickson a lifetime to tell his father’s story, an uncomfortable compound of wartime heroism and peacetime violence.

The senior lecturer in English at Penn and former Washington Post reporter has authored seven previous books, including Plagued by Fire [“Arts,” Mar|Apr 2020], Hemingway’s Boat, and Sons of Mississippi, which won the 2003 National Book Critics Circle award for best nonfiction [“Arts,” May|Jun 2004]. One can imagine this memoir, Fighting the Night: Iwo Jima, World War II, and a Flyer’s Life, gestating, mutating, stirring pain, and being shelved as other, less emotionally grueling projects took precedence.

The title is a locution Hendrickson attributes to his father. It refers to Joe Paul Hendrickson’s World War II service, emblematic of the much-mythologized Greatest Generation. The Kentucky farm boy turned 25-year-old first lieutenant piloted the legendary P-61 Black Widow, a fighter-bomber purpose-built for night flying. He launched his missions on the Rita B, named for his wife, from a base on the island of Iwo Jima following the months-long battle immortalized as one of the war’s deadliest. His son describes the plane as “a small, tight orchestra of violence” with “an undeniable mystique” arising from “the idea of dark, of stealth, of working under cloud cover or in the glow of moonlight.”

In Fighting the Night, Hendrickson embarks on “a journalistic search for my father, although really for both my parents, and for some others, too, who flowed in and out of their lives.” His narrative zig-zags through time, anchors itself in vintage photographs, and is punctuated by achronological italicized passages—all attempts to pin down an elusive past. Hendrickson has clearly wrestled with how much to include, but untold family stories shadow the narrative and often leave the reader wanting more.

Fighting the Night turns out to be something of a meta-memoir—a self-conscious exploration of the extent to which memoir requires choices and elisions, of how much it suffers from gaps in the available evidence (all those missing wartime letters!) and the impulse toward discretion, at whatever cost to truth. Not to mention the storyteller’s own inevitable limitations. The narrator of a reported memoir, like an anthropologist, is both observer and participant, striving alternately for journalistic objectivity and the distinctive subjectivity that is the genre’s rationale.

Hendrickson ably mines the documentary record to describe his father’s stint in the US Army Air Forces, including a handful of particularly harrowing flights. But, with his father now gone, he laments not being able to “ask him all I long to know, as a son, as a writer, about sultry days on Iwo and freezing nights at 10,000 feet.”

The memoirist compensates with his own imaginings, and also by detouring or digressing into other wartime tales. He describes mishaps that befell other Black Widow pilots and crew members, and some of the slaughter on Iwo Jima itself. He is particularly intrigued by the Japanese commander-in-chief Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the complicated warrior memorialized cinematically in Clint Eastwood’s 2006 film Letters from Iwo Jima.

The night that Joe Paul Hendrickson fought also connotes an emotional darkness. After the war, despite his successful career as a commercial pilot, it exploded into violence that wounded his nuclear family. Post-traumatic stress disorder, less understood in that era, was one obvious factor, his son suggests. Another seems to have been a generational legacy of (male) family violence that normalized brutal punishments for minor infractions. The author’s father took his frustrations out “savagely on his sons’ backs with his belt,” or “with boards he retrieved from the basement.”

The author’s late mother suffered as well, though the details Hendrickson presents are sketchy. The couple were “woefully mismatched,” he writes, and their never-quite-dissolved,“largely sorrowful 61-year-marriage” featured “long agonies and occasional truces and part-time-living-together arrangements,” as well as tenderness and loyalty. His mother’s story could have been an entire book, Hendrickson notes. Similarly, the challenges faced by his siblings—a sister, a pilot brother, and especially two other brothers who were troubled in different ways—are mostly ignored. Of his late older brother, Marty, Hendrickson writes: “It was such a hard life, enough of it of his own making … He did some bad things … and I don’t feel like going into them.”

Over time, Hendrickson’s fear of his father receded, and his father’s emotional reserve lifted slightly. The two were able to grow closer. Attending squadron reunions, the son appreciated the camaraderie nurtured by wartime service. His father’s fellow pilots and other veterans seem to have revered him.

Hendrickson’s journey toward knowledge (“almost a carnal craving…to know more”) and reconciliation is a common theme of memoirs, and a salutary one. Embracing it nevertheless turns out to be a heavy lift for the reader, not because of Hendrickson’s failure as a writer, but because of his skill. His description of his father’s whippings induces an emotional recoil that is hard to overcome.

In both his elegant prose style and frequent references, Hendrickson reveals himself an admirer of poetry. An abridged version of Robert Penn Warren’s “Tell Me a Story” provides the book’s epigraph. Elsewhere, Hendrickson cites Robert Hayden, Sharon Olds, Richard Hugo, Robert Bly, Mark Strand, Wilfred Owen, Robert Frost, A.E. Housman, James Wright, and James Dickey, whose poem “The Firebombing” describes the flight of a Black Widow.

Hendrickson never mentions Anne Sexton. But his struggle with memory, anger, and loss evokes the title poem of her great collection All My Pretty Ones, a phrase borrowed from Macbeth. “Whether you are pretty or not,” Sexton writes, about her own flawed, deceased father, “I outlive you, / bend down my strange face to yours and forgive you.”

Julia M. Klein writes frequently for the Gazette.