Kartik Kumra’s journey from sneaker-selling side hustle to artisanal couture.

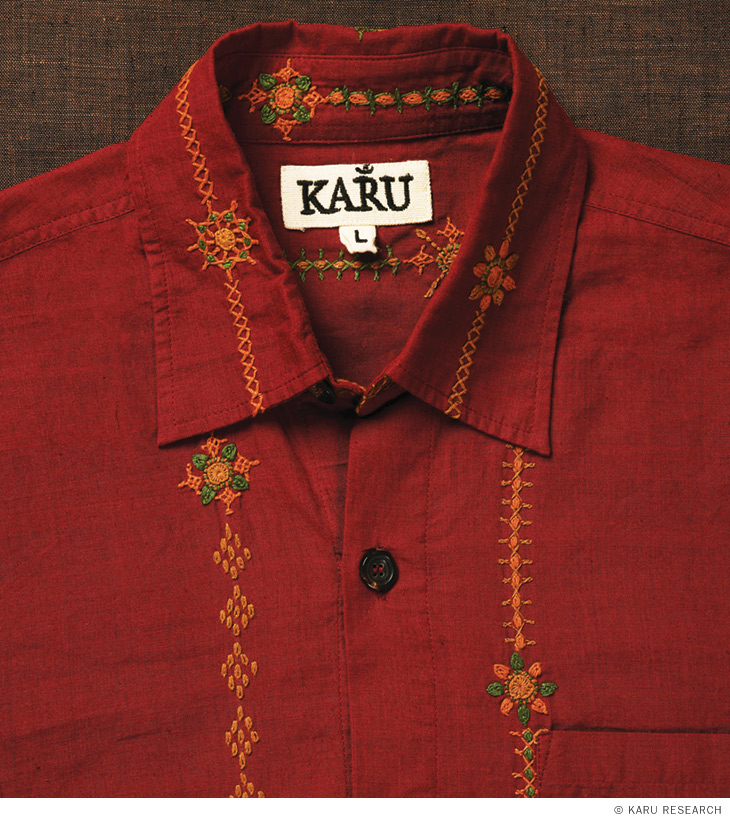

“Indian future vintage.”

That’s how Kartik Kumra C’22 describes his New Delhi-based menswear line Karu Research, whose handcrafted celebrations of his cultural heritage have made the 23-year-old a rising star in the global fashion industry.

Trendsetters like actor/singer Joe Jonas and rapper Kendrick Lamar have snatched up his embroidered camp shirts, quilted jackets, block-printed silk shirts, patchwork pullovers, and blazers with pockets woven from banana fibers. Bloomingdales carries his line. So do upscale European retailers like Selfridges and Mr. Porter. His clothes are pricey. An alpaca-bouclé cardigan goes for $835.

Even before Kumra graduated from Penn last year, the Wall Street Journal was quipping that “in the time it takes some students to pick a major, Mr. Kumra has fleshed out an impressive fashion business.” Vogue India spotlighted him with a 10-page feature this spring. As a feather in his couturier’s cap, LVMH, the parent company of Christian Dior and other luxury brands, named him one of 24 semifinalists out of 2,400 applicants in its 2023 young fashion designers competition.

What began as a teenage side hustle reselling sneakers and gear online has morphed into something that has astonished Kumra. “I wasn’t expecting it to grow like this,” he says. “It started as more of a hobby, and then it spiraled into something very real.”

When pandemic restrictions began in March 2020, during his sophomore year, he left campus to return to his home in India. The thought of doing a virtual summer internship at night with a finance company left him cold. Nor was he especially eager to pursue a career in economics. He realized he faced one of those “rare times” that gave him a chance to make a name for himself in a field he loved.

The business began in his bedroom. Having never studied clothing design, he spent hours on YouTube to teach himself sewing tips and to learn how luxury garments are constructed. Kumra, whose favorite designers are Jonathan Anderson, Dries Van Noten, and Kiko Kostadinov, studied books on the French fashion house Maison Margiela. He stitched sample creations.

But he had no suppliers, let alone supply chains. In fact, he had no contacts in India’s apparel industries at all.

Using money saved from his sneaker-selling gig, he hit the road—sometimes with his mother. Kumra had no driver’s license, so she ferried him 190 miles to Jaipur. He met weavers, dyers, and embroiderers—many of whose families had made clothing for hundreds of years. (Karu means ‘artisan’ in Sanskrit.) His search for suppliers took him further and further afield: from Andhra Pradesh, 1,150 miles south of New Delhi; to West Bengal, 900 miles to the east. It took him six months to convince a wood-block printer to create designs for his silk shirts. But little by little he amassed a reliable network of 50 small-scale independent master craftsmen.

Today Kumra takes pride knowing that all his clothes, except for their zippers, are made in India, by Indians who use locally sourced, natural materials. “The premise behind the brand is to work with the masters of the Indian handicraft sector to recontextualize my country’s rich cultural heritage,” he says. “The brand’s values are to focus on the preservation of domestic handicraft.”

In a recent Instagram post, he explained that “the idea is to inject humaneness into clothing, to provide meaning to garments we make through having a literal story and real people making the clothes. If you look around, there are actual processes happening. It’s hard to not feel enthusiastic about clothing when there’s this much going into it. The idea is—how do we keep these crafts going? By working with real people like handloom weavers, hand embroiderers, kantha embroiderers [a technique like quilting]. It’s a way of injecting meaning into clothing before the wearer even uses it, which is a fairly unique thing I think we can achieve in India.”

Running a start-up business while still in college was rough. To meet Penn’s schedule, as a remote-learning junior he took virtual classes late at night in New Delhi, nine hours ahead of East Coast time. Then he slept from 4 a.m. to 10 a.m. before huddling with artisans during the day. Back on campus as a senior, he rose before dawn for supplier updates and did the same at midnight as the workday began at home.

He sold his first pieces on Instagram. The response exceeded his expectations. He soon struck a deal with an apparel wholesaler who would approach retailers. His revenue tripled in a year, albeit from a modest beginning. His 55-piece spring/summer 2023 collection is sold in 22 stores.

“I started the brand as a response to not seeing my heritage presented in the right stores,” says Kumra. “I knew there had to be a way to translate my country’s textile language for a global audience. The long-term goal is to build India’s luxury fashion export to the world.”

“It’s really a Catch-22 for him,” cautions Angelique Raina, founder of the New Delhi-based Intuition + Strategy brand consulting firm. “His understated line communicates a version of India that a Western gaze might understand. He will find more success in other countries because of this. Realistically, Indians need the West to approve first before anything back home is considered valuable.”

That’s a reality that Kumra accepts. “I’ve just followed the demand. India will happen eventually. So far, we’ve tapped into a South Asian diasporic pride, which has really helped the brand grow quickly,” he says.

For now, three or four times a week he visits the studio near his home where his clothes are made. “It’s very chill,” says Kumra. “A lot of tea breaks. Take in cricket if you’re here in the afternoon. It’s a good place. It’s been the basis of where I’ve been able to form my brand.”

—George Spencer