“When they die well,” said the count, “it is the pride I feel.”

By Beth Kephart

Traffic was light and the air around us steamed as we took the road from Seville towards Moron.The olive trees on either side of the thin asphalt strip suggested silver in the sun, a haze of leaves above determined, knuckled roots. The storks and the occasional roadside vendor seemed to be waiting for a cloud. The sunflowers were rioting, as sunflowers will. Cortijos—farmhouses—were slouching on the horizon. There were four of us in the car that day—my husband, my son, my brother-in-law, and myself—and it was June, extremely hot. We were travelers in a foreign land, on our way to see the count.

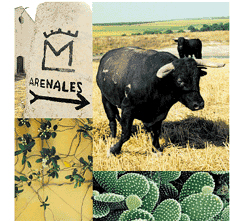

When we found the whitewashed post that announced Arenales, the count’s 7,500-acre estate, we turned left and took the narrow road past horses, sunflowers, olive trees, lush, leaking prickly fruit. The steady heat seemed to have leveled all the sounds. It was silent as we parked, silent as we walked a pebbled path beneath acacias, silent until we rapped our knuckles against the door and woke a pack of dogs.

It was the count’s wife who rescued us from the yipping creatures—she who led us through a door, through a vestibule, beneath stained ceiling coffers, and past thick velvet curtains into the company of bulls. They looked down at us from the double-height walls, no trace of remorse on their taxidermy faces, no smack of the obvious irony, no impact on the count’s well-coifed wife, who resumed her needlepoint. When Count Leopoldo Sainz de la Maza himself appeared, we stood; he told us not to. At 73, he was tall, straight-boned, and elegant in faded jeans and scuffed work boots. Only one of his blue eyes was real, I knew, the other having been replaced by glass, and if his native tongue was Spanish, he clearly loved his English, too, loved infusing Americanisms with his charm. He’d been a soldier once, that much I knew, and then the king had made him a count. And he was a legend in polo circles, was once the mayor of Moron, was a precocious businessman and farmer. But what the count was best known for was his breed of toro bravo—bulls so aggressive and brave they were sometimes spared the death sword, the highest honor any bull could ever muster. The count himself, though, was the gentlest of men. He left the room and returned with Cokes, while his wife worked her threaded needle.

We sat and we talked about Spain, about war, about all the novels not yet written. When he grew bored with the talk and when our Cokes were all done, he stood and stretched, invited us to look around. “See my house,” he said, and so we followed him—stopping whenever he did to note the wainscoted walls, the fantastic floor planks, the once-pink velvet curtains, the hundreds of books, the portraits in substantial silver frames: The count with the king, the count with Orson Welles, the count with Tipper Gore, the count with Malcolm Forbes, the count slaying one of his own black bulls. “You fight your own bulls?” I asked. “A beautiful thing,” he answered. He gestured for us to follow. We did—out the kitchen door and into the blinding sun, where a battered jeep was waiting. “Climb in,” he told us, and far beyond the house we drove, into fields of bleached-out grass, past forests full of quail and deer. A good bull has a nice straight back, the count told us, as he drove. A particular geometry of horns. A genuine camaraderie with his brothers. A good bull will fight, will want to fight. He’ll enter the ring when he is four. It was like being on an African safari, bumping along in the yellow dust, all these bulls, these beautiful bulls, running right alongside of us. Look at his back, the count would say. Look at his beauty, he’d exhort. Look at his horns. Look at his posture. Look at that one, there. I shall choose him for the next corrida. And when he goes, so will his brothers.

Estocada is the bullfighter’s word for instant kill. In the bullrings of Ronda, Seville, and Madrid, the count would watch the estocada of his bulls.

“But doesn’t it pain you,” I asked, from the back of the jeep, “to see your own bulls die?” A woman’s question. An American question. I asked it anyway.

“Not if they die well,” the count said. “When they die well, it is the pride I feel.”

“No remorse?” I pressed.

“None. No remorse. Bullfighting is poetry and mind.”

The bulls ran with us. It was an open jeep; I held my son. We went up and around on the mogul-like earth, the yellow dust like soft rain on our faces. A bull can run in a straight line fast, but he is awkward on the turns. The count kept us safe in his battered jeep by turning when the bulls got too close.

It was later in the day by now, but it wasn’t that much cooler. Still, at one point it was time to head back to the house, and so the count drove—on a ridge, beside a reservoir, past the thoroughbreds and a lonely mule and a stand of evergreens. He parked beside a bullring, his own bullring, where he had fought and killed his bulls, and then he walked us around to a thatched-roof ring, which was encircled, majestically, with flowers. Flowers in buckets, flowers in barrels, so many flowers in pots. Big and red like lush geraniums. Delicate and pink, like common phlox. Violet and stalky like no flower I’d ever seen. “What is that?” I asked him, for he was standing by me: “Never,” he said, “never, never ask a farmer about flowers.”

We stood then, just this gentle count and me, while my husband, son, and brother-in-law went off exploring. He told me about April and May, his favorite months of the year. He told me about quiet, and how it changes through the day. He told me about green-tailed birds that, like the flowers, he could not name, and about all the trees that he could. His one blue eye was glass. His other blue eye was real. He would pass away within the year. But in that moment in time, he still ruled all of Arenales—all of the bulls in all that soft yellow dust, all the living that he loved for its brave dying.

Beth Kephart C’82’s fourth book, The Unbridled Imagination: Reclaiming the Dream of Childhood, is due out next spring from W.W. Norton.