No matter where Lilian Garcia-Roig paints, Cuba is lurking in the background.

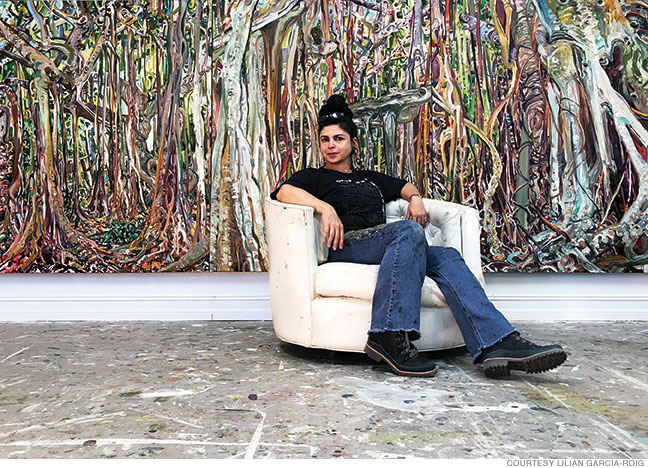

When Lilian Garcia-Roig GFA’90 paints—her long dark hair piled high on her head reminiscent of Frida Kahlo—she looks just as lost as she feels.

Garcia-Roig’s gigantic landscapes seem to envelop their creator. Painted on massive canvases that are sometimes grouped in assemblages of a dozen or more panels, they leave no spot uncolored, and they’re messy—filled with crooked trees whose twisting branches and dangling root runners seem to form an inescapable mesh.

Garcia-Roig is not easy to place. The 53-year-old married mother of two looks Cuban, speaks with a Southern accent, and paints like she was born deep in a forest and is trying to claw her way out.

There’s truth in all of those things.

She was born in Cuba but left with her parents in 1968 when she was just shy of three years old, fleeing the Castro regime to settle in Texas. Though she has no memories of living in Cuba, Garcia-Roig says that for as long as she can recall, she’s always been searching for where she really belongs.

“When people ask me where I’m from, I always say, ‘Where I was born? Where I grew up? Or where I live now?’” she says. “I was the ‘wrong’ Latina in Texas,” she adds, of a state where almost 90 percent of Hispanic residents are of Mexican descent. “I’ve always been searching and not 100 percent figuring out that I belong anywhere.”

She feels most comfortable, she says, in isolated, untidy places like the middle of the woods.

While she may be conflicted about her identity, she’s confident about her art, which she developed during her graduate studies at Penn.

“My work has always been described as strong or passionate or engaged or maximal,” she says. “But I’ve always been a person who didn’t want to pick between one thing and another.”

She’s Cuban and American. A rubgy player who loves to be draped in long, show-stopping necklaces. “I try to break as many rules as possible while still trying to make it make sense,” Garcia-Roig says.

She discovered a particular talent for painting when she was a child and relished the attention she received from it. After studying art and business at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, she came to Penn with the hope of making a career out of her passion. Her MFA led to a prestigious fellowship at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and her path was set. She started focusing on her vocation and her identity and how to connect them, painting massive landscapes filled with prickly branches, tons of leaves, and cluttered wilderness.

“Why do I always like the wilderness instead of ordered gardens and open views?” she asks, rhetorically. “I like places that no one cares about and no one bothers to look at … I’m connecting with them, and they give me a sense of belonging.”

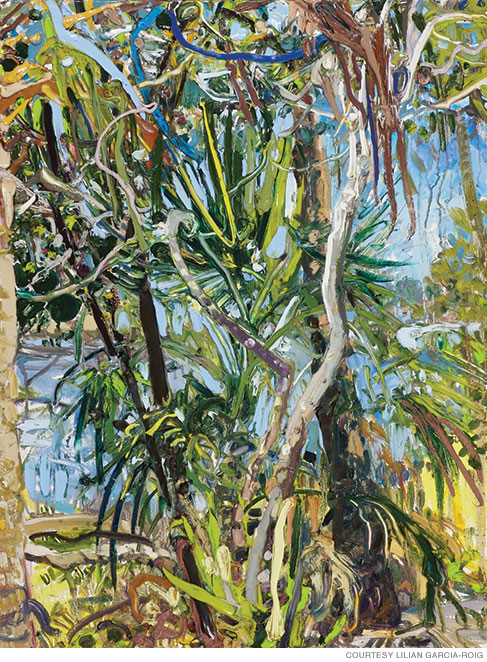

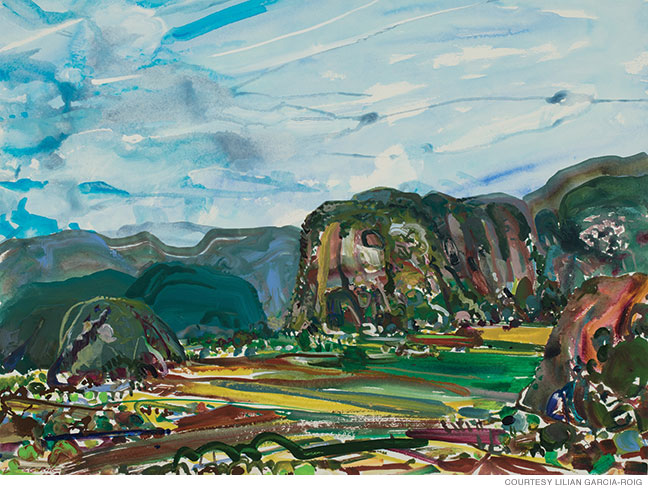

Yet two of her most recent series show Garcia-Roig, who since 2001 has been an art professor at Florida State University, branching out into new conceptual terrain. One, titled Hecho En Cuba, features oil paintings she painted in Cuba in 2017 in the same spots as other Cuban painters including Armando Menocal, Leopoldo Romanach, and Esteban Chartrand.

But her aim went beyond simply representing iconic Cuban landscapes. Garcia-Roig says she tried to reconcile her American and Cuban identities within the works.

Her research on the history of Cuban landscape painting had led her to 19th- and 20th-century depictions of the Vinales Valley, which has vast, sweeping bucolic scenes of the countryside, so Garcia-Roig headed there.

“I concentrate on trying to capture those views, hence creating work that could be inserted into the canon of Cuban on-site painting,” Garcia-Roig says.

Like her US landscape paintings, trees and foliage cover these canvases—but the Hecho En Cuba series is more serene, with blue skies and blurred lines, leaving more to the viewer’s imagination. The forest is not quite so tangled or dense in her Cuban collection.

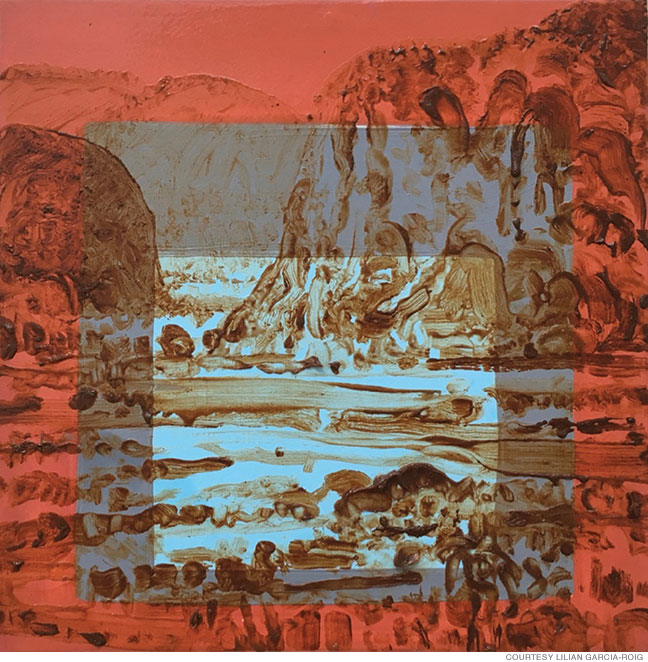

After returning to the US, Garcia-Roig created a companion series: Hecho Con Cuba. Using pigments derived from soil she’d collected from the Vinales Valley, she painted monochromatic versions of some of the same Cuban scenes, superimposed on abstract color fields whose arrangement suggests that the world we see depends on the prism we hold up to it.

—Danielle Braff