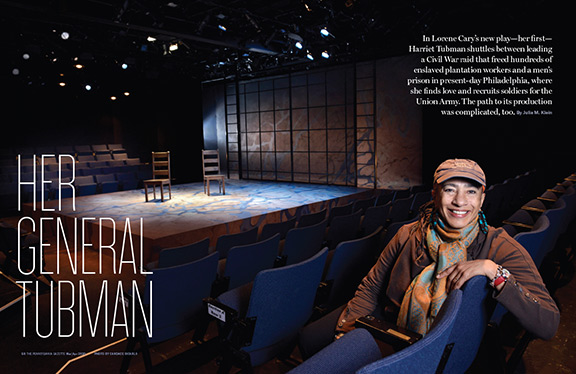

In Lorene Cary’s new play—her first—Harriet Tubman shuttles between leading a Civil War raid that freed hundreds of enslaved plantation workers and a men’s prison in present-day Philadelphia, where she finds love and recruits soldiers for the Union Army. The path to its production was complicated, too.

By Julia M. Klein | Photograph by Candace diCarlo

“So I have this scene,” Lorene Cary C’78 G’78 is saying over a salad of fried Brussels sprouts. “I keep trying to think what the hell to do with this scene.”

The acclaimed author and senior lecturer in Penn’s Department of English is describing her passion for Harriet Tubman, the legendary Underground Railroad conductor who also spearheaded a daring Civil War raid. “For certain subjects,” says Cary, “you just get obsessed and they lodge, like a cyst.”

That obsession has blossomed into Cary’s first play, in which a time-traveling Tubman appears at a present-day Philadelphia prison to enlist men to the Union cause. At once fanciful and historically resonant, My General Tubman, like many new plays, morphed through an arduous multiyear development process. Originally scheduled to run from January 16 to March 1 at Philadelphia’s Arden Theatre Company, the show was extended, by popular demand, through March 15. It coincides with a cultural moment that has spawned Erica Armstrong Dunbar C’94’s biography, She Came to Slay; the film Harriet, depicting Tubman’s escape from slavery and early Underground Railroad days; and a debate over adding Tubman’s image to the $20 bill.

But the “very specific origin” of Cary’s literary interest in Tubman was simpler: a glimpse, about a decadeago, of an iconic photograph at Historic Cold Spring Village, a living-history museum in Cape May. The South Jersey shore resort is a favorite haunt for Cary and her husband, Robert Clarke Smith, an ordained minister. Tubman’s connection to the town was spending summers as a housekeeper and cook at the Cape May Hotel. Cary kept envisioning Tubman walking along the shoreline and watching dolphins cavorting in the waves. “They looked like family, and they looked like freedom, they looked so pretty, and the sound [they make] is like laughing,” Cary says.

That image “ended up getting dropped into the emotional center of an opera treatment” about “two men in love,” a project titled His. One character, in despair over being gay, describes walking into the ocean, at age 13, determined to drown. “And Tubman was there,” says Cary, “and she sang in a voice the color of memory, and pulled him out.” Tubman tells the would-be suicide: “I married a man [John Tubman] who wanted me to lie still, but God made me to run. And God made you just the way you are. You find someone to love you just as you are, then you’ll understand why I’m taking you out.”

That was the scene that stayed with Cary, haunting her. “It’s got to be opera,” she thought.

Opera Philadelphia, which has become a nationally respected incubator of new works, encouraged Cary to develop her gay-men-and-Tubman idea. But finding the right composer proved a challenge, and, in the end, the company decided not to commission the piece. “Dead in the water,” Cary says of the nascent libretto.

“I tried to write this as a short story,” she says. “It didn’t work.” And she knew she didn’t want to write a novel about Tubman. “It felt to me,” she says, “like a story that needed performance.” What’s more, “the opera had told me that this is my time of leaving strict realism.”

That’s when Cary, a regular theatergoer, turned to the Arden, a nonprofit regional theater whose mission is “bringing to life great stories by great storytellers.” Cary and Terrence J. Nolen, the theater’s cofounder and producing artistic director, had met in 2003 when Cary’s historical novel, The Price of a Child, was named the inaugural selection of the Free Library of Philadelphia’s “One Book, One Philadelphia” program. Nolen had read the book, and the Arden had sponsored a reading of excerpts. Afterwards, he and Cary occasionally corresponded about theater.

Nolen says he delighted in those email exchanges: “The way in which she responded to the work that she saw here was something I really valued. I appreciated her perspective. I loved her writing and how she captured ideas, even in emails.” He also admired Cary’s social activism, especially her service on the now-defunct Philadelphia School Reform Commission, which he calls “heroic.” In theater, he says, “relationships are everything. And connection.”

So it wasn’t a gargantuan leap for Cary to approach Nolen, in February 2016, and ask if he saw her gay love story as a potential musical. “No, I don’t, actually,” Nolen told her. “I see it as an opera. I see it as a possible movie.”

But their conversation continued, with Cary telling Nolen facts he hadn’t known about the historical Tubman. She recounted how, at the end of the Civil War, Nelson Davis, a consumptive African American Union soldier, had walked from Texas to Auburn, New York, to knock on Tubman’s door and ask her to nurse him back to health. In 1869, they were married.

“That’s amazing,” Nolen recalls saying. “That sounds like a play. Is that a story you’re interested in writing?” Cary said it was.

My General Tubman was commissioned under the auspices of the Arden’s Independence Foundation New Play Showcase, which supports the creation of new plays and musicals. “Commissions are, in some ways, an investment in a particular writer’s voice,” Nolen says. They “buy a little bit of time, make a little bit of space” to develop a project. But they are no guarantee that the Arden, which has unveiled 45 world premieres since its 1988 founding, will produce a specific show. “I invest in process,” Nolen says.

Cary’s career has been marked by a penchant for experimentation and challenge. As a writer, she has explored contemporary fiction (Pride), memoir (Black Ice and Ladysitting: My Year with Nana at the End of Her Century), young adult history (Free!: Great Escapes from Slavery on the Underground Railroad),and historical fiction (The Price of a Child and If Sons, Then Heirs). She wrote the video scripts for the President’s House exhibition on Philadelphia’s Independence Mall, telling the stories of nine enslaved African Americans in President George Washington’s household. Inspired by her work on His, she successfully sought a residency in the American Lyric Theater’s Composer Librettist Development Program, completing a one-act libretto, The Gospel According to Nana, based on Ladysitting.

A West Philadelphia native who now lives in the city’s Graduate Hospital neighborhood, Cary also has been a committed teacher and activist. In 1998, she founded Art Sanctuary to bring African American arts to local audiences [“Alumni Profiles,” Jul|Aug 2000]. On the School Reform Commission, she worked to eliminate zero-tolerance punishments. She has created a website called SafeKidsStories.com, to which her Penn writing students contribute [“Gazetteer,” Jul|Aug 2017]. One offshoot of that site is #VoteThatJawn, a project to spur registration and voting among 18-year-olds. Cary also has taught writing classes at the Philadelphia Detention Center, another inspiration for My General Tubman.

“If I could,” Cary says, “I would just write. It’s the joyous thing I do. It’s the thing I feel I’m built for.”

But her activism is impelled by a sense of duty: “I feel like I have gotten every single break there is, and from where I came from, that’s what it takes to live a satisfying life. Everything in my community, everything in my family, everything in my race, says, ‘Each one, grab one’—because somebody got me. Or else where would I be?”

Cary’s first big break—“an intervention in my education,” she calls it—was winning a scholarship to attend the elite St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire, which was trying to diversify its student body. She would later chronicle that experience in Black Ice, her literary debut. Praised for its candor and lyrical prose, the 1991 memoir recounted both her alienation and her gradual adjustment to the private boarding school. She would eventually return both to teach and to serve on the school’s board of directors.

Cary entered Penn loving biology and thinking she might become a doctor. But her parents had just separated, causing financial, as well as emotional, stress. (Divorce rippled through several generations of her family, Cary writes in Ladysitting.)Strapped for money, Cary worked odd jobs up to 40 hours a week, and her grades suffered.

The study of literature and creative writing, with professors such as Houston A. Baker (now a Distinguished University Professor at Vanderbilt University) and Sonia Sanchez (Philadelphia’s first poet laureate), became a refuge, “the thing I can do with one arm behind my back.” She excelled, earning both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in English and winning a Thouron Award, which financed study at Sussex University in England.

After Europe, Cary toiled, not always happily, as a writer and editor at magazines such as Time and TV Guide, where she met Smith. Both were married to other people at the time. He was also nearly 17 years older, white, and her boss. “Everything was wrong! Nothing was right,” she recalls. “As Bob says, ‘If Dr. Phil had seen us, he would have said: ‘Don’t do it.’” They did it anyway, and have two daughters. (Cary also has a stepson and four grandchildren.) As a former editor, Smith is her first reader; she sings in his church choirs.

“As often happens, when people have remarried, when it works, it’s because you’ve been able to find a better self with this new person,” Cary says. It’s not surprising that she was intrigued by both the happiness and improbability of Harriet Tubman’s second marriage, to a man about two decades her junior.

Cary, whose paternal grandmother, Nana (the central figure in Ladysitting), was so fair-skinned she could pass for white, says she often wearies of talking about race in America. But “I’m always thinking about it,” she adds. “I suppose I write about it because it’s the way I can discipline myself to think about it without just rolling into rage.”

African American—and American—history figures prominently in Cary’s work. The protagonist of The Price of a Child, based on an actual incident, is an enslaved woman whose escape entails leaving her youngest child behind. If Sons, Then Heirs, whose themes include family estrangement and the importance of land ownership, is set mostly in the present. But it unfolds against the backdrop of the Great Migration of African Americans from the agricultural South to the industrial North. It draws on a family story about Cary’s maternal great-grandmother’s first husband, who was said to have been lynched after a state fair. “I realized that I was exorcising that,” she says.

In her historical fiction, Cary says she took facts seriously, writing “history with a corset on.” Now, with her Harriet Tubman story, she was ready to take the corset off—admittedly, she adds, “a funny thing to say about the 19th century.”

When Nolen first read a draft of My General Tubman, in January 2017, he was caught off guard. “When I started reading about the Philadelphia Detention Center,” he says, “that was the first time I learned that that was going to be part of the story. I was absolutely surprised when I saw that she was going to be mixing the past and present in the way that she does, but was totally thrilled to see where that was going to lead.”

Cary’s stint as an instructor at the Philadelphia Detention Center, a medium- to maximum-security, short-term facility, was an “intensely spiritual experience,” she explains. “I felt that there was more going on than we could see.” There was “so much wounding: wounded people are brought in and are wounded more.” The prison sequences became central to My General Tubman. Like Moses, to whom she was compared, the historical Tubman led her family and hundreds of others out of slavery; in the era of mass incarceration, Cary’s Tubman dissolves prison walls, finding new love in the process.

In the first script Nolen saw, the character of Nelson Davis, destined to become Tubman’s second husband, is introduced as the prison warden of the Philadelphia Detention Center. (In later drafts, he is a Coast Guard veteran, unjustly imprisoned when he attempts to protect his sister from a pedophile uncle.) And in the 19th-century scenes, the pivotal character of John Brown, the abolitionist martyr who seeks to enlist Tubman’s help at Harpers Ferry, had yet to appear.

The first weeklong workshop of My General Tubman, in September 2017, was followed by notes and revisions. But the next workshop, in July 2018, went awry, both Nolen and Cary say. Unhappy with the direction the work was taking, Nolen called a halt partway through the allotted week. “I’d come up lame, unable to revise and rethink completely,” Cary says. “I was floundering.”

Nolen took the aspiring playwright out for coffee and encouraged her to take a step back. He asked her to reflect on her favorite plays and what she loved most about theater. Cary mentioned Shakespeare’s history play Henry V, with its famous St. Crispin’s Day speech (“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers …”). The play was already one of the sources for My General Tubman, and Nolen encouraged her to “lean in” to that model. He suggested adding a Chorus whose narration would mediate between the audience and the characters. As a result, says Cary, “I found a rough structure. And confidence.”

As she honed her work, Cary says she sent occasional drafts to a “secret mentor,” William B. Anawalt, who holds a master of fine arts degree in playwriting and chairs a theater company board. Cary also listened repeatedly to YouTube workshops by Lauren Gunderson, described as the country’s most produced playwright (Ada and the Engine, I and You, We Are Denmark, etc.). “She was like my intro class and my master class,” Cary says. “When she mentioned a book, I read it.” Gunderson, like Cary, has used Shakespeare as source material.

Two more workshops of My General Tubman followed. To cap off the second, in December 2018, the Arden invited about 50 guests to attend a reading. Their enthusiasm clinched Nolen’s decision to add the evolving play to the Arden’s 2019–20 season, even though “every time you do a new play, there’s a risk,” he says, “and there’s a leap of faith.”

In October 2019, cast members have assembled around a conference table for a final workshop for My General Tubman. Cary, radiating warmth, greets a visitor. She’s casually dressed, in slacks and sneakers, with a brown jacket, her hair in dreadlocks, and big, dangling earrings. “It’s new, and I’m new,” she says of her playwriting debut. Nolen enters and envelops Cary in a hug. “I am so excited about this play,” he says.

The director, James Ijames (pronounced Imes), who is also an actor, playwright, and assistant professor of theater at nearby Villanova University, advises the cast to read for “meaning” and “story.” Cary specifically wanted an African American director. With Nolen’s support, she tapped Ijames after being wowed by his epic, Barrymore Award-winning production of August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean at the Arden in the winter of 2019. Like My General Tubman, the Wilson play contains surrealistic and visionary elements.

Ijames informs Cary that he has meticulously charted her play’s time shifts. Over two acts, the action alternates between the run-up to John Brown’s doomed Harpers Ferry raid and the Civil War, on the one hand, and the contemporary prison where Tubman periodically materializes. She is summoned, magically, by the prisoners’ drumming, a reference to the spiritual practices of Tubman’s Ashanti ancestors. Tubman’s temporal lobe epilepsy, the result of a head injury, permits her to float through time and space. Some characters can see her; others cannot. How exactly it all works remains something of a puzzle.

Over the next few months, Cary will consolidate, sculpt, and rearrange scenes, as well as clarify the rules of Tubman’s time travel. The role of the Chorus—who speaks in both prose and Shakespearean iambic pentameter, injects humor, and helps orient the audience—will expand. Other sequences, including a “dream circus” involving Tubman and Davis, will disappear.

Ijames recognizes Cary’s fascination with the history and her struggle to braid exposition into the play. But, at the end of the October reading, he offers this advice: “If there’s anything historical that’s not advancing plot,” he says, it needs to go.

It’s December 20, 2019, a few days into the five-week-plus rehearsal period—a week longer than usual because the play is “a loose and baggy monster, still,” Cary says. The mostly bare rehearsal space, where the actors are still holding scripts and trying to find their characters, is framed by tables, chairs, a coat rack, and a coffee maker. These are long, exhausting days, and all the actors and members of the production team have designated mugs.

This morning, Ijames is working intensively with Danielle Leneé, who stars as Harriet Tubman. In the current scene, Tubman is relating a story from childhood, when one of her tasks was to empty muskrat traps, to a roomful of Northern women whose donations she’s soliciting for the abolitionist cause. Leneé wants to know how big the traps were, so she knows just how large a gesture to make.

Ijames is thinking more about character and context: “She is fighting perceptions not only of her, but of black people writ large. The intellect of that is kind of breathtaking. … I don’t want to clutter that up with a lot of business.” A few minutes later, he adds: “She’s probably surrounded by nothing but white people. There’s quite a bit of not being herself completely and not being able to completely relax.”

While Ijames runs rehearsals, Cary’s presence is essential. She interjects an occasional comment, but, mostly, she is there to hear what’s working, and what isn’t. “They’re trying like hell to figure this out, they’re arguing with themselves, with the text,” she says. “If anything’s in the way, that’s why I go home and try to figure how to make it better, make it right.”

With guidance from Ijames, Nolen, and freelance dramaturg Michele Volansky, Cary retreats to her desk for hours each night to revise, putting in a double shift. For a novelist, the collaborative process can be daunting. “I don’t like a lot of hand-holding,” says Cary, “and I don’t like a lot of company. I write because I want to get in that world. I don’t write because I want to work together with other people. So, for me, theater and playwriting has been a bit of a challenge—’cause I like to write up on the third floor by my damn self. I love it. I love the aloneness.” But she says that, in the end, “a deep joy”—as well as better art—emerged from the Arden collaboration.

Volansky—who is also associate artistic director for PlayPenn, which specializes in new play development—says much of her work with playwrights involves dramatic structure. When she first read My General Tubman in October 2018, she was drawn to what she calls “a remarkable story and a lively vision.” But “the balance of past and present didn’t feel quite right to me,” she says, nor did “the balance between urgency and character exploration.”

All the key players on the production team, she says, agreed on two ideas: “One was to look at Harriet Tubman as someone other than this iconic figure—she was a human being. And that her legacy endures today through a variety of different ways that we deal with the systems that oppress and keep people down. That’s the nature of the prison sequences.” But the question, she says, was, “How do the scenes from the past inform the present—and vice versa?”

In general, Volansky says, she sees two different kinds of plays. Some “get the balls in the air really easily and then it’s time to figure out where they go, and things fall apart in the second act. Or it’s the opposite,” she says. “In this case, it was trying to set up the rules of the world that I think was a challenge.”

By January 3, less than two weeks before the start of previews, Cary is feeling buoyant. “I have a final script!” she declares.

She doesn’t, really—she’ll keep tweaking until opening night. But she is much closer. Working with Volansky, she has cut 30 pages from a lumbering 80-page first act, bringing the show’s total run time to about two hours. “Everything had to be faster, cleaner, sharper,” she says. The main change was to make Harriet Tubman “more dominant, give her more agency.”

The scene being run in rehearsal today, from the second act, is perhaps the play’s most dramatic. It involves Tubman’s leadership of the 1863 Combahee River Raid, in South Carolina, which concluded with hundreds of formerly enslaved plantation workers being transported to freedom on Union ships.

In an earlier scene, Tubman has rallied her black troops with a version of the St. Crispin’s Day speech, reminding them: “We have crawled on our bellies through time/ Itself to do this new thing together.”

They’re enthusiastically behind her now. But meanwhile, (unseen) plantation workers, afraid of being left behind, are swamping the small boats meant to ferry them to the larger Union vessels. And Union soldiers are fending them off violently with their oars.

To stop the clamor and the carnage, the resourceful Tubman climbs atop a platform and improvises lyrics to the tune of the Battle of Hymn of the Republic: “We’ve got room on Lincoln’s gunboats/ Plenty room for you and me/ We’ve got soldiers in the small boats/ Rowing back and forth, you see./ The government has sent us here/ And means to set you free:/ Our God is marching on!” Her troops add their voices to the chorus.

“This is a great moment,” Ijames says. “Let’s gather around. Let’s learn this song together.” As they sing, an ebullient Cary joins them.

During a lunch break, she describes her creative process: “Stories are down there, and you’re swimming along, and you’re the fish, and for some reason that bait pulls you—like in a dream where you’re the object and the subject both. In this case, I’m also fishing. I don’t always know what there is about that story that I need.” She adds: “The real urge is to make beauty from it,” to find “where spirit touches aesthetics.”

Tubman’s story “is part of the American story, so I want to serve it up and put it on the table,” Cary says. “I want to share what it felt like to think about this woman who came up with [the notion of] ‘making a way out of no way.’ It had to be a play, there has to be music, it has to be funny, there has to be drumming, there has to be spectacle—all of these crazy-ass things, all in one play.”

In the stage directions, Cary describes her aims this way: “This play asks how HT gives and receives love. The answer is that she gives and receives The Big Love. And she manifests God’s love despite evil. America does not deserve HT or her leadership. But we have her. Like Nelson this play is trying to figure out how to go back in time and adore her.”

The first preview, on January 16, is actually the second time a paying audience has seen My General Tubman, following a “Pay What You Can” dress rehearsal. (One of Tubman’s descendants showed up at the rehearsal, giving the cast an emotional jolt.) The show is in the Arden’s intimate Arcadia Theatre, with the audience arrayed in a horseshoe configuration around the stage. Melpomene Katakalos’s set is uncommonly spare. Crisscrossing the floor and backdrop are networks of blue squiggles resembling both rivers and veins, and possibly meant to suggest the osmotic quality of time. Jordan McCree’s sound design, dominated by drumming, further unifies past and present.

Leneé’s Tubman is stately and dignified, while Aaron Bell’s Chorus character is deliberately arch, inviting the audience into the story. But, given the serious subject matter, the preview crowd isn’t always sure when—or whether—to laugh. The first act seems to just peter out. One audience member, a Civil War buff, says she would have preferred more emphasis on the past. But the Civil War scenes and the love story between Tubman and Davis are stirring, and the audience responds with measured warmth.

By opening night, January 22, the show is noticeably improved. The Chorus has gotten some new lines. The first-act ending has been sharpened. There are more laughs, too. During intermission, Cary says she fine-tuned the script during previews because “it took a long time for people to realize they had permission to laugh.” The audience, filled with members of the Arden’s board of directors and other donors, gives My General Tubman a standing ovation.

At the reception afterwards, Arden board president Robert Elfant W’73 buttonholes Cary, and tells her how much he enjoyed the show. “So many things could go wrong,” Cary replies. “So many things have to go right for this to do well.”

“It worked beautifully,” Elfant reassures her. “Everyone I talked to wants to know more about Harriet Tubman now.”

Finally, there are the reviews: respectful, if not full-out raves.

In the Broad Street Review, an online publication covering the Philadelphia arts scene, Cameron Kelsall commends the Arden’s “finely wrought” production, while suggesting that Cary made some “rookie mistakes.” He cites the device of an “overexplaining” Chorus, prison characters who exude “the faint whiff of cliché,” and an overly “mystical aura” around Tubman herself. The review concludes by declaring that “in its best moments—and there are many—My General Tubman gets under the skin of a complex woman and shows us the ways we still walk the path she forged. And it shows the work our society still has left to do.”

In the Philadelphia Inquirer, John Timpane praises Cary’s play for its combination of “history, bloodshed, heroism, love, and magic,” as well as “a succession of surreal, moving scenes.” He sees the show as losing “momentum and focus” in the second act. And he offers an optimistic prediction: “This hot property will continue to develop, find about 10 to 20 minutes it can profitably lose, and emerge even warmer.”

“We just ran out of time,” says Volansky, who argues that a play is never really finished. “There are always questions to ask. It’s just the nature of the work.” But of Cary’s gutsiness, she has no doubt. “She swung for the rafters,” the dramaturg says.

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, writes frequently for the Gazette. Her stories on Eli Rosenbaum W’76 WG’77 and Eva Moskowitz C’86 won the American Society of Journalists and Authors’ award for Outstanding Profile in 2018 and 2019. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.