A new biography sheds more light on Penn’s most famous and infamous poet—and his poetry.

By Samuel Hughes

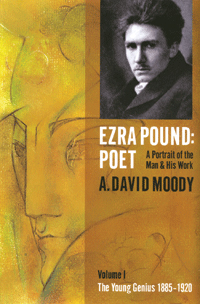

In July 1907, shortly after getting pushed out of the doctoral program at Penn by (among others) English professor Felix Schelling, Ezra Pound C1905 G1906 wrote an essay that was something of a cri de coeur. It was “apparently provoked by Dr. Schelling’s telling him that he was wasting his time,” notes A. David Moody in the first volume of his trenchant new biography, Ezra Pound: Poet, “and provoked also by the charge that he lacked originality.”

Talk about fighting words.

“When one stumbles on a flaming blade that pierces him to extacy” (sic), wrote the indignant 21-year-old in a prose-verse hybrid, “is he to hide it … or to cry some greater truth higher and more keen.” Placing himself in the company of Browning and other poetic royalty, and being “continuously filled with burnings of admiration for the great past masters,” Pound announced that he would “strive upward a riveder le stelle”—to see the stars at last.

Those were Dante’s words in the Inferno upon emerging from hell. That Pound would use them after escaping from the “hell of philology” at Penn (Moody’s phrase) was, on several levels, right in character. After all, the University was only the first of many hells that Pound would fashion for himself on the rocky road to paradise, and Dante’s hendecasyllabic universe was already an obsession for the embryonic Modernist.

Even before entering Penn at age 15, Pound had told his father: “I want to write before I die the greatest poems that have ever been written.” Moody’s subtitle—The Man and His Work—makes it clear that the biographer intends to examine Pound’s poetry and prose as well as his personality and politics. He succeeds, often brilliantly—providing thoughtful insights into everything from the derivative mysticism of Hilda’s Book to the caustic refinement of Hugh Selwyn Mauberly to the artful translations of Cathay to the revolutionary early Cantos. (I can’t recall any other biographies devoting 15 pages to Canzoni, whose stilted language inspired such hilarity on the part of Ford Madox Hueffer.)

Volume 1, The Young Genius: 1885-1920, covers the formative years of Penn’s most famous poet-alumnus in considerable but judicious depth. Pound was still an engaging, if maddening, character in those days, and had yet to descend into the darker hells of fascism and anti-Semitism, the Gorilla Cage of Pisa and St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. His growing fame was owing to his uniquely crafted verse, his skills as a literary impresario, and his critical acumen, as well as his truculence.

Moody, the author of a well-regarded biography of T.S. Eliot, distills the early American part of Pound’s odyssey into about 60 efficient pages: from his boyhood in the Philadelphia suburb of Wyncote and his undergraduate years at Penn and Hamilton, to his aborted attempt to get a Ph.D. at Penn, to the disastrous stab at professorhood at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana—that “sixth circle of hell,” from which he busted out through repeated assaults on Midwestern and academic mores. Though one could argue about this episode or that character getting short shrift, Moody is a skilled and patient tracker who not only finds the choicest details but does a masterful job of putting them in context.

The bulk of the volume is devoted to Pound’s dozen years in London, when he went from an upstart nobody to an icon-smashing superstar. There he befriended his hero, William Butler Yeats, who wrote: “To talk over a poem with him is like getting you to put a sentence into dialect. All becomes clear and natural.” And there he became a flamboyant fixture of the literary scene—one who would “perplex his English hosts” by “combining a love of beauty with American drive,” Moody notes:

His apparently inexhaustible energy was frequently remarked, and frequently put down as restless and tiresome. They would say that he broke the legs of chairs because he could not sit still, and that he played tennis “like a galvanized, agile gibbon” … They would deprecate his dominating the conversation and holding forth to his elders on the mysteries of their art. He read his lyric poems rather loudly and in a Philadelphia accent which sounded barbarously of the Wild West in their English ears. In short, he broke what Ford Madox Hueffer had observed to be the “general rule” of London society, the rule against animation.

By 1914 that animation was transmogrifying into what Yeats described as a desire “to insult the world.” Yet even those who were put off by Pound’s “promptness with the cudgels,” as the then-unknown poet Marianne Moore told him in a letter, could be treated with great kindness and generosity—as long as they met his lofty artistic standards. (See Eliot, T.S., and Joyce, James, among many others.)

The women in Pound’s life are intelligently presented, starting with Hilda Doolittle CCT’09, his first love and the daughter of Penn astronomy professor Charles Doolittle. Dryad, as he called her, became the inspiration for his first collection of poems and nearly became his wife; she soon became famous as H.D. (another Pound moniker). Moody also does a good job synthesizing the recent research regarding Margaret Cravens, who quietly subsidized Pound at a critical stage before committing suicide in Paris in 1912. Then there is Dorothy Shakespear, who was immediately smitten with the young poet’s aesthetic sensibility and eventually married him. (“It is not easy to combine Cavalcanti’s idealized lady and the Artemis type,” notes Moody dryly, “but that is … perhaps what he saw in Dorothy.”)

Among the male actors in Pound’s huge supporting cast is William Carlos Williams M1906 Hon’52, who befriended Pound his first year in medical school and bore with him for six volatile decades [“Moderns in the Quad,” April 1998]. (“He was the livest, most intelligent and unexplainable thing I’d ever seen, and the most fun,” wrote Williams about Pound in their Penn days. “He was often brilliant but an ass.”) With all these witnesses—and Pound himself—Moody is an erudite jurist who takes all the evidence into account.

Only toward the end of Pound’s London years did dribs of anti-Semitism begin to appear. At that time they were few and far between, and usually tempered by context—after one snark about Jews beating their swords into pawnshops, he added: “Inasmuch as the Jew has conducted no holy war for nearly two millennia he is preferable to the Christian and the Mahomedan.” (For Pound, every religion was an “attempt to impose a thought-mould upon others.”)

But while anti-Semitism may have been endemic in those days, Pound, “being engaged in a war against clichés and stereotypes and false generalizations, should surely have been among the objectors,” Moody notes. “Those remarks indicate a flaw that was to grow, in the 1930s and after, into a most grave failing. We will come to that in its proper time and place [i.e. Vol. 2]. The troubling questions won’t go away.”

Two cavils. One is Moody’s punctuation, or lack of it, which sometimes suggests an academic Gertrude Stein; this reader found himself blinking and rereading certain sentences more often than he wanted to. Then there is this, shortly after the publication of Pound’s Personae: “A Philadelphia newspaper owned itself ‘jealous of the fact that England should have discovered his genius rather than his own native America, but we are duly proud of him as a son of Pennsylvania.’” That “Philadelphia newspaper” was Old Penn, the alumni publication that, nine years later, would change its name to The Pennsylvania Gazette. A nitpicking distinction to be sure, but it does alter the meaning of son of Pennsylvania.

Volume 1 ends in May 1921, when Pound, having worn out his welcome in London, had fled for Paris with Dorothy. There he wrote to Ford Madox Ford (né Hueffer), his friend and mentor: “One seems to have emerged from the murk of England a riveder le stelle.”

Heaven was now on the Continent. But new hells awaited.

Senior editor Samuel Hughes won a Pennsylvania Council of the Arts award for his screenplay about the youthful romance of Pound and Hilda Doolittle. He is still delusional enough to think the movie could sell some popcorn.