A leader in two worlds.

By Felicity Wood

After landing in Douala, Cameroon, we hired a taxi driver to take us six hours north to Bamenda. Soon he stopped, explaining that he needed “to buy chocolate for the car.” At least, that’s what it sounded like. Though I studied French for eight years, I’m always on the lookout for misinterpretations. But this time I was right—the driver returned with a pot of chocolate spread. At a gas station on the edge of the city, he painted the spread on the numbers on the car door. This was to hide the fact that his vehicle didn’t have the right papers to travel.

I was in Cameroon at the invitation of a former teacher of mine at Penn, Dr. Godlove Fonjweng G’93 Gr’97, to make a video documentary of a ceremony initiating him as leader of his extended family. (Godlove’s relatives would have been there to greet us at the airport, but the “storm of the century” in Paris caused Air France to cancel our flight; the soundman and I arrived in Douala days later than planned and on a different airline.) Godlove had suggested that I do the documentary after having heard that I had purchased a video camera and taken a course on expedition documentary filmmaking.

Going to Cameroon was a gamble; I borrowed lots of money to do it and even missed a week of graduate school. What made me want to do the video is that I have a deep belief in people’s ability to run their own lives. Godlove is such an example of a successful person, from a place that, in the United States, is commonly perceived as “needing help.” I thought that making a video of this ceremony to share with Americans would send a profound message.

I first met Godlove when I was an undergraduate in Bob Giegengack’s environmental-studies class, and he was one of the teaching assistants. Watching him in the front of the room or handing out photocopies in that class of 500 students, I remember thinking there was something so modest, so joyful, yet so capable about him. In fact, he embodied the essence of what he is now—a leader.

The son of a poor church minister who had made a living from crushing palm nuts for oil, Godlove first came to the United States in 1986 to attend college. He and his brother, Isaiah, had sold life insurance throughout Cameroon from their VW bug in order to raise funds. Without much other information on universities here besides the library at the U.S. Embassy in Cameroon’s capitol, Yaonde, he picked the University of Delaware. “I wanted to be not too far north where it would be cold, nor too far south where it would be hot and humid. Also I was seeking proximity to oceans and major cities. I really wanted to see D.C., New York and Philadelphia. Delaware embodied all that,” he says.

Godlove was first in his class freshman year, but running out of money. At the suggestion of a geology professor at UD, John Wehmiller, a Swarthmore alumnus, he transferred to that university, completing his undergraduate education under full scholarship. He went to Penn for his master’s degree and doctorate in geology. Today, he lives with his wife and two sons in their home in New Jersey. (Godlove’s father died in 1987, a year after Godlove arrived in the U.S. He was not able to return to Cameroon until 1989. Since he started working, he has returned about once every three years.)

Cameroon is known as “Africa in miniature” because the topography ranges from desert in the far north to savannah in the middle to rain forest in the south. The northern part of the country is mostly Muslim, and the southern mostly Christian. Its two official languages are French and English. French and Korean companies are logging heavily in the country. The government is a parliamentary system under President Paul Biya. The opposition party, the Social Democratic Front, is headquartered in Bamenda, near Godlove’s village, Njikob (pronounced jeekob or just kob).

Njikob is set in mountains, forests and streams 45 minutes outside of Bamenda. When I was there, in January, we wore hats and jackets at night and snuggled into our sleeping bags. The days were crisp and bright. However, red dust from the roads and ash from burn-offs of mountain fields caused me to lose my voice for a few days. Boulders are strewn throughout the village, and there is one impressive cliff-face, for which the town is named. Njikobmeans “rock” in the Metta language.

Njikob is in the English-speaking part of Cameroon. It has no electricity, and no restaurants. Since it is in the heartland of the opposition party, roads are not maintained. (You could make a Jacuzzi in the pothole in front of Godlove’s house.) There is a great abundance of food, but they sure work for it. Before starting, farmers pray for the strength to do it.

I heard people say that in Cameroon there is plenty of food and good soccer, and that is keeping the country at peace. Cameroon’s national soccer team, the Lions, won the African Nations Cup held in Nigeria this year.

As it turned out, the taxi driver’s chocolate worked like a charm. The soldiers at all the army checkpoints, in their red berets and green uniforms, licked it up, so to speak. At least they didn’t fire their guns, like Godlove’s relatives did during the celebration.

We arrived in Njikob just in time for the ceremony, which was attended by about 2,000 people. First, segments of Godlove’s extended family performed a series of dances. Each subset of the family had its own new costume of brightly colored fabric from the market. Family drummers sat in the middle of the dirt compound, playing rhythms, while about 50 people in matching outfits danced in a circle around them. The first dance was the Akate, a Christian dance—though you wouldn’t know it unless someone told you. Next was the Men’s Dance. They put on grass skirts and beads and let all heck break loose, shaking their feet and their legs in a stampede in slow motion around the drummers. In one dance everybody held cut branches of trees.

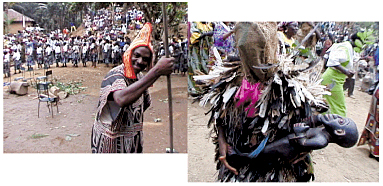

Godlove invited a village near the top of the nearby mountain to perform the Ladder Dance. Masked dancers on super-tall stilts jigged and shook around the compound, rolling their heads on their necks, causing the crowd to “ooh” and “aaah” and applaud. Special leaves had to be strewn in the stilt-walkers’ path, or else any woman who crossed it would not be able to menstruate.

A short, masked juju-dancer shimmied in a sack of feathers and brandished a black wooden statue, scaring everyone, including the other dancers. Because Godlove’s father was a Christian, the juju was only for show. Apparently, real juju, or “masquerade dancers,” can do things like make your mouth and nose melt and your face turn green, until you undergo another ceremony to get better.

The next day, the anniversary of his father’s death, there was a private family ceremony at which the “family girls”—the term refers to any female relative born in the village; some are 75 years young—transferred power to Godlove as his father’s successor as family leader. In preparation, the girls yelled and sang and danced while they cut up bull’s horns and ate raw meat from the skulls. According to Godlove, some dance groups perform this ritual to appease the gods and protect themselves from evil spirits.

Later, when the plantains and other food were prepared, male elders dressed Godlove in a sweeping black outfit with red and yellow figures embroidered on it. The elders placed an embroidered hat on his head, with earflaps down to his shoulders. They gave him his father’s cup—a sawed-off bull horn, with the edges smoothed so he could drink from it. They poured palm wine into the cup, and all the family members drank. The girls made offerings of money and cola nuts into his palms and chanted and sang, “Thanks to Godlove, we are one.” The offerings were to acknowledge and enhance his power as the new leader.

Now, besides heading the environmental-studies program at Philadelphia University (formerly the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science) and teaching geology at Penn, Godlove is the leader of his extended family in Njikob. I guess it makes sense that a town called Rock would have a leader trained in geology.

Felicity Wood C’92 is studying for her master’s degree in urban planning at the School of Public Policy at UCLA. A 20-minute clip of her video was shown at the Africa Summit in Washington in February.