An apology to Loren Eiseley.

By Carl Hoffman

Some three decades ago, I was a first-year anthropology graduate student. Twenty-two years old and very much a product of that era, I bopped around the halls of the University Museum in my unvarying uniform of black T-shirts, torn jeans, and wild, curly hair growing down to my butt. One late afternoon in early spring, with its washed-out March sunlight streaking languidly through windows stained with decades of Philadelphia smog, I turned a corner and found myself looking up into the craggy face of a world-renowned literary icon.

It was none other than Loren Eiseley, an emeritus professor in the department, making one of his rare visits to his old office, mostly to collect his mail and catch up on his correspondence. Much of that consisted of copies of his books—The Immense Journey, The Firmament of Time, The Invisible Pyramid, The Unexpected Universe, The Man Who Saw Through Time—which devoted readers from all over the world sent to him to be autographed. For Eiseley had long ago abandoned the arrow-points and skulls and stones and bones of human evolution to write books of intensely thoughtful, deeply personal, brooding essays that had attracted a small but worshipful audience—almost a cult following—in almost every country in the world.

He gazed down at me, first with a look of puzzlement, then with a look of frank distaste that slowly hardened into a glower of utter contempt. The great Loren Eiseley—anthropologist, naturalist, and highly acclaimed literary essayist—was staring down at me disdainfully as though I were a bedbug. With the arrogance and self-importance that comes so naturally to young men in their twenties, I walked away from him and thought to myself, “Well, Hell! If that’s the way he’s going to look at me, then I won’t read any of his goddamned books!” Youth really is wasted on the young.

Ten years later, bored with academe, I decided to take my Ph.D. and—as they used to say in their recruiting ads—put it to work in the Peace Corps. The Peace Corps sent me to the Philippines and posted me up in the mountains with a remote hill tribe. The tribe, in turn, lodged me in a little bamboo-and-grass hut that had housed a previous volunteer years before. Settling into my new digs, I noticed that my predecessor had left behind a few old paperback books, which were moldering away in a corner of the hut. Whoever he was, my Peace Corps forerunner had an eclectic taste in literature: The Innocents Abroadby Mark Twain, Call it Sleep by Henry Roth, The Stories of John Cheever, and—at the bottom of the pile—The Night Country by Loren Eiseley. I grabbed Eiseley’s book—its yellow pages festooned with mold—and instantly remembered his angry glare in my direction a decade before. But with Eiseley then dead some seven years and I 10 years older, forgiveness was total and heartfelt. As night fell, I hunkered stomach-down on the bamboo floor, propped myself up by the elbows and—by the dim flickering light of an soot-blackened oil lamp—proceeded to read.

Most of us make our judgments about a book by reading the first few pages. By the third or fourth page, we have often already determined whether or not the rest of the book will be worth our time, not to mention our failing eyesight. The Night Country, however, grabbed me right away in the author’s foreword:

… Though I sit in a warm room beneath a lamp as I arrange these pieces, my thoughts are all of night, of outer cold and inner darkness. These chapters, then, are the annals of a long and uncompleted running. I leave them here lest the end come on me unawares as it does upon all fugitives … There is a shadow on the wall before me. It is my own; the hour is late. I write in a hotel room at midnight.

Tomorrow the shadow on the wall will be that of another …

and then hurled me, breathless with surprise, into the book’s first astounding paragraph:

In the waste fields strung with barbed wire where the thistles grow over hidden mine fields there exists a curious freedom. Between the guns of the deployed powers, between the march of patrols and policing dogs there is an uncultivated strip of land from which law and man himself have retreated. Along this uneasy border the old life of the wild has come back into its own. Weeds grow and animals slip about in the night where no man dares to hunt them. A thin uncertain line fringes the edge of oppression. The freedom it contains is fit only for birds and floating thistledown or a wandering fox. Nevertheless there must be men who look upon it with envy …

I continued to read, almost mesmerized, even as the pages cracked in the corners and the binding came apart in my hands. As the night outside my hut deepened and the human noises from nearby huts slowly gave way to the muffled roar of a million cicadas, Eiseley told me about the night—a country I thought I knew like the back of my hand:

… Man who bumps his head and fumbles in the dark because of his small day-born eyes, fears the ghosts of the dark above all things. Maybe that is the real reason why men string lamps far out into the country lanes and try to run down everything with red eyes that happens to waddle across the road in front of their headlights. It is cruel but revelatory: we are insecure, and this is our warfare with the dark. It began when man first lit a fire at a cave mouth and the eyes he feared—very big eyes they were then—began to blink and draw back. So he lights and lights in a passion for illumination that is insatiable—a poor day-born thing contending against one of the greatest powers in the universe.

An old man who had done almost all of his writing late, late at night, was speaking to a younger man who liked to read in those same dark hours. In a chapter entitled “One Night’s Dying,” Eiseley said to me: “It is thus that one day and the next are welded together, and that one night’s dying becomes tomorrow’s birth. I, who do not sleep, can tell you this.”

Today, well into my fifties, in the midst of a lifetime of almost compulsive reading, I still regard The Night Country as my all-time favorite book. On a lucky day, a determined seeker can find one or another of Eiseley’s books in second-hand bookstores, filed under everything from “Science” to “Philosophy,” “Literature” to “Anthropology.” I myself have lately obtained most of my Eiseley collection in second-hand shops in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

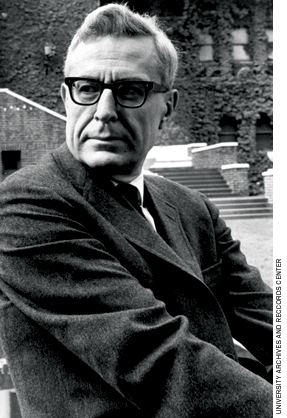

These days, on a wall of my office, facing my desk, hangs an eight-by-ten-inch portrait of Eiseley. Directly in my line of vision, right above my computer monitor, he glowers down at me with the same intensity as he did that spring day in Philadelphia, more than 30 years ago. Occasionally, at the end of a hard day—in moments of the kind of fatigue that comes only to middle-aged men trying to do a younger man’s job—I stare back into those intense eyes and say to him, “Professor Eiseley, I’m sorry that I had neither the maturity nor sense of humor to take your unfriendly scowl in stride. I’m sorry that I lacked the wisdom to realize that in 1975, lanky old men in tweed suits simply didn’t like the sight of long-haired hippie kids running around their Ivy League universities. But most of all, I’m sorry I let you push me away, sorry that I was too young to empathize with an old patrician’s fear of the barbarians at the gate. I apologize for not trying to break through, to reassure you, to get to know you, and to learn from you while you were still here to teach.”

Carl Hoffman G’76 Gr’83 currently lives in Israel with his wife and two children. He is a contributing editor of ESRA Magazine and contributes occasional articles to The Jerusalem Post.