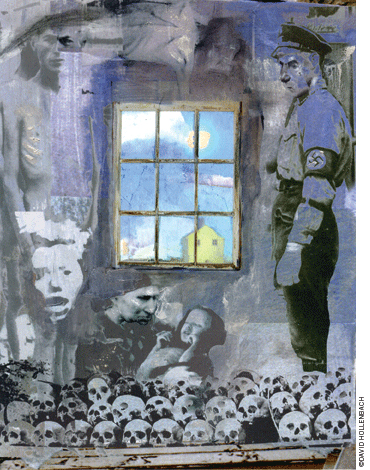

My grandmother was meant to die under these windows on this frozen concrete floor.

By Leora Klein

The grey morning sky was clogged with heavy wetness. Snow drifted across the windshield of our heated van. Eddie, the young Israeli who was my driver and translator, turned to me: “You couldn’t have picked a better day for this?” It was February in Vienna, and it was cold. “My grandmother walked nearly naked in this weather,” I blurted out. “I don’t think I can complain.”

As the van snaked its way through the cobblestone streets leading away from my hotel, I thought of Safta and her capable, soft, dancing hands. I am the granddaughter of four Holocaust survivors—and Safta, my mother’s mother, is my final living connection. Safta’s hands, frozen during the war, never stop moving, teasing and touching the life around her. She tells me she survived her internment in Lichtenworth because she washed her only pair of stockings every day. She would rub the frozen pipe with her raw hands until water mixed with blood. Dignity lies in cleanliness. “I was the only 18-year-old who survived in my bunker, because I was clean,” she says, defiance ringing through her memory. She would put the wet stockings on her body in temperatures so low that the stockings would freeze on her legs.

Armed with a destination, a camera, a notebook, and an insatiable need to understand, I had come to Austria to find my grandmother’s concentration camp—to see the place where she escaped death and madness.

Lichtenworth was a small camp of 2,000 Jews and rarely makes it into the history books. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington located the camp—a former factory building—one mile northeast of Weiner Neustadt and an hour outside Vienna. They also have record of a beautiful castle where my grandmother recuperated after liberation. “They knew of the castle?” Safta kept repeating when I shared the findings with her, as if the mere mention of Lichtenworth by a research librarian legitimized her memory.

A chain of directives from the Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance in Vienna (an extensive archive of Austrian persecution by the Nazis) and Yad Vashem in Israel (The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority) led me to an address for a memorial stone in Lichtenworth—which turned out to be the village information center. When I asked where the concentration camp was, the woman behind the desk looked at me like I had six heads. She picked up the phone and the next thing I knew my German-to-Hebrew translator was excitedly telling me, “Rosh haear bah!” The mayor is coming!

Is he going to ask us to leave? I wondered.

Mayor Alois Proksch was about 10 years younger than my 78-year-old grandmother. He had liquid blue eyes and spoke fine English. He assured me that there was in fact a memorial stone, the camp was still standing, and although the castle was destroyed in 1951, he would show me the land upon which it had stood. Every year on April 2, liberation day, buses of Hungarian women come to visit the camp and he takes them out to lunch. The image of elderly ladies dressed in furs and pearls climbing down from a school bus and having Wiener schnitzel with the mayor made me laugh. I was nervous.

The entire village of Lichtenworth, with its rambling countryside and small gingerbread-like houses, is 3,500 people—barely more than the number of Jews interned there on their way to Auschwitz. A one-minute drive took us to the memorial, a stone block about the size of a framed diploma, on the side of the road. We got out of the van and the mayor translated the words etched in stone. It commemorated the death of 300 people from lack of food and typhus and 52 citizens who also perished from typhus. I knew the numbers were wrong, but I said nothing.

There was no mention of the word Jew or of the Holocaust. The memorial was hidden under the thick weight of arbor, next to a bus stop on a road that runs through town. You could wait for a bus there every day of your life and not notice it. I dared not insult the mayor as he beamed over his plaque. I simply started to photograph the stone, and then the stone under the trees, and then the stone and the trees next to the bus stop. I had to show the right perspective. It was like a pencil stub under a desk in a dark classroom. Would I dare show this to my grandmother?

From the memorial we drove to the building that had been the camp, and to my horror it looked like a postal-service center: large white-painted-brick building with a sign painted a friendly U.N. flag-blue. Modern, clean, and now in use as a parking garage. With little idea of what to do, I started photographing the building from every conceivable angle. A woman soon came out—pretty, in her early forties, well-dressed and wearing funky glasses. “What are you doing?” she asked.

I explained in English that my grandmother had been here and I was hoping to photograph the factory. She looked at the mayor. “She came all the way from America to see this?” When he said yes, she looked at me again with cynical amazement and said she could show me inside.

“Yes please, yes that would be great, please,” I sputtered. I was too grateful for her simple offer and scared to lose the opportunity.

The four of us walked through the back door. Row upon row of cars took the place of row upon row of the bodies my grandmother had described. I looked up from the cold concrete floor and there were the windows. The windows I had always heard about. My breath stopped.

The mayor said, “The windows and the floors are the same since 1944; they are the original.”

The woman, who owned the building, stood close to me—almost too close. She wanted to see what I saw. She wanted to know why I had come so far to see this dirty floor and a triangular row of windows. Her English was excellent, and I couldn’t help but think she could be the child of a Nazi who fled to South Africa.

I could barely speak. This was a camp for Hungarian Jewish women, and two of them were pregnant, I said. One young girl was giving birth during an air raid when a full pane of glass fell directly on her. The glass didn’t shatter, and no one was hurt.

I looked at the ceiling where they had replaced the fallen pane.

Despite the birth, neither survived the war. The baby died days later. The mother couldn’t produce milk, because there was no food to feed herself.

By now the woman was crying, and so was I. I felt like an imposter because this isn’t my story. I wasn’t there. But I had to tell her what happened here in order to tell her why I was there. My grandmother was meant to die under these windows on this frozen concrete floor.

The woman thanked me. Every spring, buses of old Hungarian women come and she never knows why, she explained. In that moment, I knew she has been pretending not to be there on that memorial day—but this year she would come to meet them and let them in.

The mayor, the translator, and the woman were looking at me, and I didn’t dare look back at them. I wished they would leave me alone in this room filled with junked cars. I took seven steps forward to hide behind a busted truck and I took my siddur out of my bag. I know Safta survived but so many others did not. For them I said kaddish.

The words Holocaust, war, survivor, and Jew were never used that day. We danced around the obvious, avoiding the names and the words that Jews are often accused of overusing. Their absence was dangerous. As I look back on that day, I feel a sense of encroaching disaster, as if the whole world past, present, and future should end. But I would be unworthy of my grandmother’s survival if I dropped into selfish despair. I would be unworthy of her survival if I did not try to remember something I know I cannot fathom but something we cannot afford to forget.

Leora Klein C’97 is a writer and teacher living in New York. She worked at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles for two years.