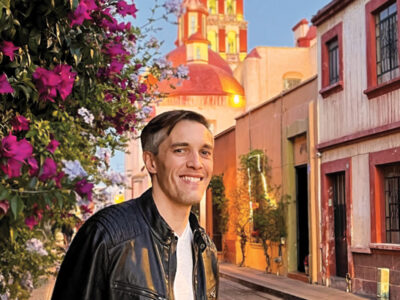

Four ambulances sped away from Philadelphia International Airport into the cold darkness of 5:30 a.m. Inside were three women, a little boy, and his father. Riding in the ambulance with the boy and his father was Naomi Rosenberg, a 28-year-old, second-year Penn Med student. She held the four-year-old’s hand. “We’re going to take care of you,” she promised.

Lights and sirens blaring, the ambulances caravanned onto I-95, headed for the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Orthopedic surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses waited in the emergency room. As the ambulances’ doors opened, the trauma team got their first look at the patients.

Bloody and dehydrated, hair caked with dirt, skin streaked with ash, they wore the clothes they had been buried in. The tendons, muscle, and skin of their crushed legs lay in mangled messes on the white sheets of the gurneys.

It was January 17, 2010, five days after the 7.0-magnitude earthquake shattered Haiti. HUP was about to become the first medical center in the United States to treat earthquake survivors. Richard Shannon, chair of Penn Medicine, stepped towards the women. “Welcome, my friends,” he said in Haitian Creole.

How the Haitians were plucked from death and debris to be at HUP is a story that began the day of the earthquake—but also five years, 15 years, and 20 years before it.

Twenty years ago, Paul Farmer and Partners In Health (PIH), a global network that brings medical services to impoverished communities, established a field hospital in Cange, Haiti. Cange is where Shannon volunteered his medical expertise 15 years ago. Five years ago, Rosenberg worked in the same hospital.

Rosenberg spent three of her post-undergrad years working for PIH at its Boston headquarters. Part of her job was to convince hospitals in the United States to accept Haitians for life-saving care—free of charge. Hospitals didn’t come forward easily. “We usually had to wait until a patient was so sick that we would say to the hospital, ‘Without surgery, this person will die within 24 to 48 hours.’”

The patients PIH did evacuate had been treated by hospitals in Boston. None had been accepted by a Philadelphia hospital. That was about to change.

Rosenberg and Shannon, with their shared Haitian history, were in positions to put Penn Medicine to work for earthquake survivors. Three days after the earthquake, Rosenberg emailed Shannon. “I wrote, ‘If we can get earthquake victims out of Haiti and into the United States, will HUP accept them and care for them?’

“Within four minutes, he answered me,” she recalls. “‘Bring them here and we’ll take care of them.’”

Shannon then called Garry Scheib, chief operating officer of Penn Medicine and executive director of HUP to relay PIH’s request. Shannon thought it would involve two or three adults, and he did not know their injuries. “Without hesitation, Garry said, ‘Absolutely,’” Shannon recalls. On the ground in Haiti, which was still trembling with aftershocks, PIH staff began to identify patients who would survive the trip to Philadelphia.

The next day, Saturday, January 16, Shannon was at home when his phone rang. It was Rosenberg, saying that she had succeeded in her humanitarian manipulation of the State Department, Homeland Security, and USAID. The Haitians had been granted medical visas.

At midnight, Shannon got another call from Rosenberg. The patients had just arrived in Ft. Lauderdale on a donated medevac. The helicopter would refuel and leave for Philadelphia. And, Rosenberg said, there’s a fourth patient: a four-year-old boy with severe leg injuries.

“I didn’t know he was on board until the medevac nurse told me,” Rosenberg said.

Shannon called Madeline Bell, a senior administrator at CHOP. Would CHOP take care of this child? “Without hesitation, Madeline said, ‘Yes. This is what we do.’”

At 4:30 a.m. that Sunday morning, Shannon’s phone rang again. It was Rosenberg, calling this time from a cab on her way to the Philadelphia airport. “The Haitians are arriving in 45 minutes,” she told Shannon. “We’ll be at HUP in an hour.”

When the HUP trauma team got its first look at the Haitians’ injuries, they knew that they needed more help.

At 6 a.m., Samir Mehta’s phone rang while he was in the shower. Mehta is chief of HUP’s orthopedic trauma and fracture service, and an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at the medical school. The caller was William Schwab, chief of HUP’s division of traumatology and surgical critical care. Patients had arrived from Haiti with severe crush injuries, Schwab said. How fast could Mehta get to HUP?

Minutes later, L. Scott Levin, chair of HUP’s department of orthopedic surgery and a professor of plastic surgery, checked his email. The Haitians had arrived at HUP. They needed Levin’s specialty: reforming the soft tissue of severed extremities so that they heal correctly and can be fitted for prosthetics.

Which meant that the Haitians needed amputations.

The smell of gangrene emanated from the dying legs of the patients lying in HUP’s ER trauma bay. “Each of the women had the most hideous leg injuries that I’ve ever seen,” Shannon later recalled.

“One woman had a crushed opened tibia fracture with a necrotic foot,” Mehta said. “Half the leg and the foot were hanging from pieces of skin and soft tissue onto the remainder of her body.

“Right next to her in the trauma bay was a second patient. She had a crush injury to her left leg. The injury—the weight crushing her leg—caused pressure to build to the point that it crushed blood vessels, muscles, tendons, and nerves. The injury was to her entire leg, from ankle to thigh. Everything was dead, or completely useless. The leg needed to come off.”

But the patient was systemically sick. While she had lain amid the earthquake rubble, her dying leg muscles had released toxins that polluted her system. “We couldn’t take her into the OR the way that she was,” Mehta said. “She went to the ICU for four or five hours of aggressive resuscitation.”

The third woman had an open wound with debris in it. “And she had significant degloving injuries,” Mehta explained. “Her leg was skinned from her ankle to just below her knee. It looked like someone had taken a knife and flayed her leg.”

At 9 a.m., Mehta performed a transtibial amputation on one of the women. In a nearby operating room, Levin worked on his patient’s degloved leg. “We went to extreme measures to try to save it,” Levin said. “But the injury was so severe that saving the leg was not an option.”

Three hours later, the third patient had been stabilized for surgery. Mehta removed half of her leg with an above-the-knee guillotine amputation.

The cost of the Haitians’ care, while substantial, is a drop in the torrent of life-saving treatment the Penn Health System provides to the uninsured. Last fiscal year, the system provided more than $100 million in charity and underfunded care. Its total “community benefit number,” which encompasses direct and indirect benefits including research support and physician-training support (as stipulated by the IRS), was $733 million. Meanwhile, in CHOP’s ER, the pediatric orthopedic trauma team worked on the four-year-old boy. “There was a flurry of activity around the little boy and his father,” Shannon said. “The doctors were concerned about the open wound on his leg and they were worried that his abdomen had been injured. They had stabilized his neck, head, and leg and were trying to determine the extent of his injuries.

“His father was there, right by his side, and so was Naomi. For the father, she was translating everything that the doctors said, as quickly as she could. In the middle of all of this, the little boy lay on the gurney. He was scared, but not crying. Here was a child, horribly injured, traumatized, quiet and dignified amidst this incredible backdrop.”

His leg was broken in two places and he had significant degloving on his thigh. The little boy, and all three women, required multiple surgeries. Two weeks later, all four were stable. And their doctor was in Haiti. On January 25, Mehta left for Haiti with Penn Medicine Team One. The nine-member group included orthopedic and trauma surgeons, anesthesiologists, and specialized nurses. They brought 1,200 pounds of medical equipment.

The team spent two weeks at PIH’s facility in Cagne. Two hundred beds strong, the hospital is one hour from Port-au-Prince, near the most impoverished and needy parts of the country.

As the Penn team worked in Haiti, more Haitians were brought to Penn. Working with PIH, Rosenberg secured medical visas for three children. Two were treated at CHOP. The third, a 14-month-old, had been burned over more than 20 percent of his body. Originally sent to CHOP, the boy was transferred to St. Christopher’s Hospital because it has facilities for severe, circumferential, infant burns.

What does the future hold for the Haitians? For now, they remain in Philadelphia. Rosenberg worked with a local church to find and fund a house in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia. Using donations made to PIH, Rosenberg hired contractors to make the house wheelchair-accessible. The Haitians moved in with clothing that had been purchased with donations. They now know what Target is.

Their outpatient care continues at HUP and CHOP.

The entire experience has changed the lives of the Haitians, and their caregivers. “I am different,” Mehta said. “I can’t quite explain how, but I’m not the same person or the same doctor that I was before Haiti.”

—Melissa Jacobs C’92