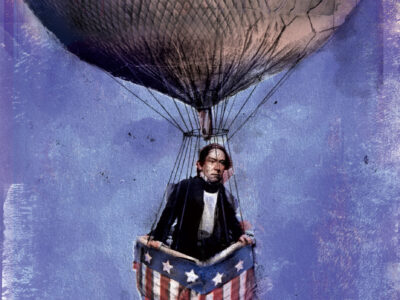

Two hundred and fifty years ago, Benjamin Franklin published the first political cartoon in America. It debuted in The Pennsylvania Gazette (the other one), and it depicted a snake, cut into sections representing the different colonies and bearing the legend “Join or Die.”

“No one before Franklin and his partner [David] Hall had published a picture that conveyed the whole issue at a glance,” said Ellen R. Cohn, editor-in-chief of The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, during a January seminar on “Franklin and Freedom of the Press.” The issue in question was the need for the Colonists to unite against the French at the outset of the French and Indian War, she explained, and during the next 25 years, the snake device would be used on numerous occasions to rally the Colonists during their confrontations with Great Britain.

Cohn, a senior research scholar at Yale University, was the featured speaker at a day-long celebration of Franklin’s career as a printer at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. To mark the cartoon’s 250th anniversary—not to mention the 275 years since Franklin began publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette—a group of organizations sired by Franklin celebrated with a seminar and a keynote luncheon address by political cartoonist Tony Auth.

This year also marks the 225th anniversary of the small press that the 73-year-old Franklin founded and operated in the Parisian suburb of Passy, while he was serving as American ambassador—also known as Minister Plenipotentiary—to the French Court. Though he had retired from active printing in 1748, it was at Passy that he began doing some of the most important printing of his life.

Until recently, the prevailing opinion was that Franklin “engaged in the difficult business of sustaining his country” by day, while by night he “put on his little bifocals and set type for fun” at his Passy Press, Cohn noted. “In fact, its purpose was much more serious.”

The Passy Press was established as a “diplomatic press,” she explained. “On the one hand to help him in his routine work as Minister Plenipotentiary, but at the same time, as part of his image-making for his fledgling country. Franklin was presenting a sense of the United States of America as a newly declared, competent, trustworthy, credible nation, whose printed forms reflected its stature.”

Almost immediately after becoming the sole representative of the American government, Franklin purchased a printing press, bought a small quantity of type, and hired a typefounder to cast type for him, eventually purchasing the typefounding equipment. The first item known to have been printed on the Passy Press was an invitation to an Independence Day party that he gave on July 5, 1779 (the Fourth not being suitable for celebration that year because it fell on a Sunday).

As the new nation’s consul in France, he printed passports, at one point using a unique typeface that became known as le Franklin. He also made use of an unusual font known as “sloped roman,” which was “neither roman nor italic.”

Perhaps the most unique work that Franklin printed at Passy was a 1782 treatise titled “A Project for Perpetual Peace,” which laid out a vision for maintaining a permanent peace in Europe. Written by a “peasant in rags” named Pierre-André Gargaz, who had appeared at Franklin’s door after walking from the south of France, the treatise contained a proposal for a central governing council—comprised of representatives of all the nations of Europe—that would adjudicate international disputes.

The egalitarian attitude that Franklin displayed by welcoming Gargaz into his house and agreeing to print the pamphlets “was so fundamentally different, not only from the French aristocrats of the day but even from the Americans,” said Cohn. (Thomas Jefferson, to whom Gargaz also sent a copy, basically blew him off.) “He could see through the rags and focus on the genius of the peasant.”

While Franklin was a “fervent champion of freedom of the press, his view of that liberty was one that carried a heavy dose of responsibility,” Cohn noted. But he also was not above pulling the wool over enemy eyes. In 1782, when he was negotiating with the British to end the war, he printed an “elaborate hoax” in the form of a fake “supplement” to the Boston Independent Chronicle that was distributed in London. It listed various atrocities allegedly committed by British soldiers in America, noted Cohn, and its sole purpose “was to influence British public opinion.”

After Cohn’s talk, the celebrators braved the bitter January cold to lay a wreath on Franklin’s grave at Fifth and Arch streets. Earlier in his life, he had written a wry epitaph (not used on the tombstone) that read:

The body of

B. Franklin, Printer

Like the Cover of an old Book

Its Contents torn out

And Stript of its Lettering & Gilding

Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be lost

For it will as he believ’d

Appear once more

In a new and more elegant Edition

Corrected and improved

By the Author.

“It is because he never lost sight of this identity that Franklin is still revered today by American printers, who consider him their patron saint,” noted Cohn. “Of all Franklin’s many identities, this one is the most fundamental.”

—S.H.