A pair of history profs teams up with Getty Images to create a public-facing, photography-oriented window into Black history.

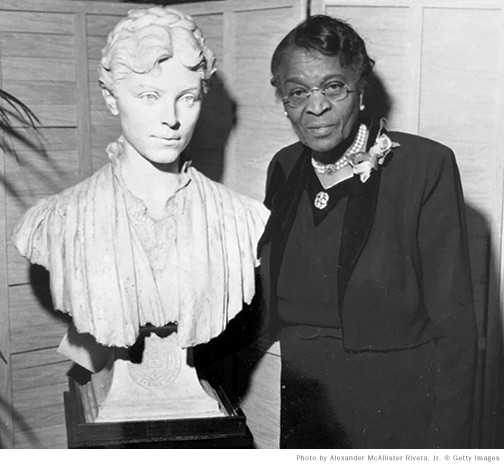

As the school year wound down this past spring, visitors to the fledgling website Picturing Black History encountered a black-and-white image with obvious resonance in the season of graduation ceremonies. Yet there was nothing immediately obvious about the photograph itself, in which a distinguished African American woman posed in a dark dress and white pearls next to a cream-colored bust of a younger woman dressed with equal elegance.

Yet as Wayne State University classicist Michele Valerie Ronnick observed in a short companion essay, “the image is packed with meaning.”

Shot in the early 1950s by the photojournalist and civil rights activist Alexander McAllister Rivera Jr., it depicted educator Charlotte Hawkins Brown marking the 50th anniversary of the Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial Institute (AFPMI), a North Carolina school she founded and named in honor of the former Wellesley College president whose bust graced the heart of campus.

Brown, the story goes, had been working as a high school babysitter when Palmer glimpsed her pushing a stroller with one hand while holding a volume by the Roman poet Virgil in the other. Palmer, who had been among the first women admitted to the University of Michigan, recognized a “kindred spirit.” She supported Brown’s post-secondary studies at the Salem State Normal Institute, where Brown trained to become a teacher. The relationship would bear many fruits, not the least of which was the AFPMI, “one of the only schools in North Carolina to offer a college preparatory program based upon a liberal arts curriculum” in the early 20th century.

This was one of that era’s many instances of “interracial sisterhood,” Ronnick suggested, in which “African American women educators were assisted in a similar way by white women philanthropists.” Perhaps the most recognizable example was Harriet E. Giles and Sophie B. Packard’s Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary. After receiving support from Laura Spelman Rockefeller, “it was renamed in honor of Mrs. Rockefeller’s father, abolitionist Harvey Buel Spelman. Spelman College is today the oldest private liberal arts college for Black women in the US.”

Rivera’s photograph, in Ronnick’s gloss, “is a portrait of American art, American ingenuity, and American success.” Everyone involved in it—including the sculptor who produced Palmer’s likeness, Evelyn Beatrice Longman—“came from humble backgrounds and rose through various vicissitudes on their own talent,” she elaborated. “It is also a visual representation of a successful Black and white alliance that was able to bring significant and lasting educational opportunity to North Carolina in the era of Jim Crow.”

The photo and accompanying essay are also emblematic of Picturing Black History, which Nicholas Breyfogle Gr’98 and Steven Conn Gr’94 launched in late 2020 as a spin-off from the online magazine Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective [“Profiles,” Sep|Oct 2009].

“There’s been an ongoing discussion among historians for two generations about the extent to which Black history is or isn’t centered in larger US narratives,” says Conn, a professor at Miami University of Ohio, noting the reductive effects of cordoning off “Black history” into a ritualized thematic month every February. With Picturing Black History—a partnership between Getty Images and Origins (which is supported by The Ohio State University, where Breyfogle is a history professor)—they aim to wield a wider lens.

“There are standard stories that we know, that we’re taught in schools—civil rights, slavery, and that sort thing,” says Breyfogle. “But there’s a lot more to Black history in America than just those stories.”

Though neither professor specializes in African or African American history, in their editorial roles at Origins both felt an urgency to expand their public-facing history offerings in that direction after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police triggered nationwide demonstrations and civil unrest.

The partnership with Getty, whose archive contains 80 million photographs, also gives the project a distinct art-history flavor. As editors, Breyfogle and Conn can let contributors—mostly but not exclusively historians—wander through the collections without limitation, but the written commentaries are supposed to engage with chosen images as visual art in their own right, not mere adornment for the text.

“That’s a really great strategy,” says Conn, “because it also distinguishes us from a lot of what’s out there from historians, who tend to use images as purely illustration—something that fills up the page but you’re not really supposed to look at too hard.”

The result is an idiosyncratic assortment that has the capacity to surprise even when the subject matter is well known. An entire generation of schoolchildren has encountered the story of Ruby Bridges, for example, filtered through photos depicting the six-year-old being escorted by US Marshals past angry protestors to desegregate an elementary school in Louisiana. But for one PBH essay, poet Chet’la Sebree presents a lesser-known image of a slightly knock-kneed Bridges beaming in an unguarded moment at the threshold of a family home—a portrait that any parent would die for, depicting not an icon but a little girl lit by the pure spark of a love-filled childhood. “I see not the brave girl marching among men paid to protect her,” writes Sebree. “I see a jovial one.”

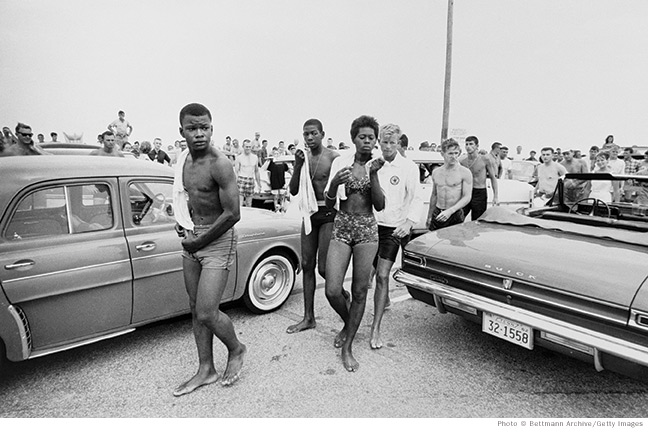

As new photos and essays are added roughly every other week, the subject matter widens: swimsuit-clad civil rights activists from Atlanta’s Morehouse College striding barefoot through a parking lot in 1960 trying to desegregate a public beach near Savannah, Georgia; queer Black people “who felt alienated from the Black church” and sought freedom of expression in late-1970s disco clubs; a mindboggling aerial photo showing smoke rising from 61 West Philadelphia rowhomes after police dropped a bomb from a helicopter in an attempt to dislodge members of the MOVE organization in 1985.

Several thematic clusters reflect the Getty Archive’s particular strengths, most notably in depictions of military service. One essay takes its cues from photos of Charles Young—circa 1884 as a West Point cadet, and in 1921 on his final mission in Nigeria. Born into slavery, Young rose to become one of the US Army’s “most senior and accomplished officers” by the time the US entered World War I—whereupon he was “forcibly retired” in 1917 because military leaders “did not want any Black officer in command of white soldiers,” which his rank and experience would have made inevitable. After riding his horse 497 miles from his Ohio home to Washington in protest, Young was reinstated—but not until five days before the German Armstice ended the war.

Another entry shows the “Buffalo Soldiers” of the 92nd Infantry Division, a “colored” unit under white leadership, clearing mines in the rubble of liberated Italian towns during World War II. Still another explores the efforts of Mary McLeod Bethune to enhance opportunities for Black women to engage in military service and defense-industry work during World War II as part of the “Double V Campaign,” which “strategically linked the need to eliminate the evils of Jim Crow with the need to end fascism across the world.”

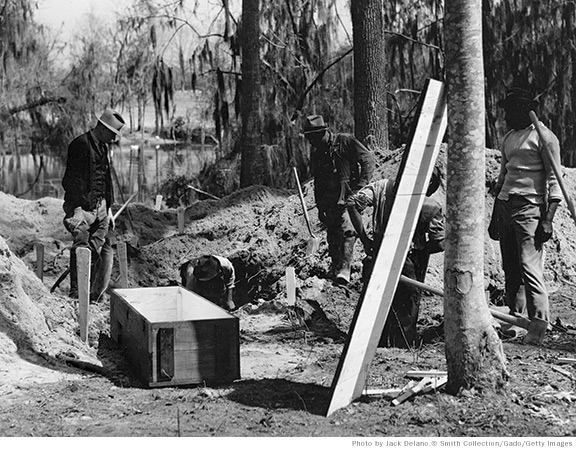

Some entries are narrow indeed. Examining South Carolina’s Santee-Cooper navigation and hydroelectric project—which was the nation’s largest New Deal-era land-clearance endeavor—through the removal or flooding of 9,000 graves, predominantly holding the remains of enslaved Africans and their descendants, may strike some viewers as a peculiar way to approach a staggering public-works undertaking marked by quite complex racial and environmental politics among the living. Yet the shadow-streaked image of men digging in that malarial swampland has a haunting power—and Picturing Black History is most engaging when it errs on the side of eccentricity rather than familiarity.

“I have been stunned repeatedly,” says Conn, “thinking about all these episodes and moments where there was a camera, and that some photographer was there to document this. I find that kind of remarkable. It’s made me rethink what photographers really do. We sort take it for granted.”

Looking ahead, Breyfogle says they want to lean further into the stories of the men and women who captured these moments on film. “One of the things we’re going to start doing more is essays from photographers … to really explore what the photographer was thinking, how he set up his photos, what he was trying to get, so that we can see these historical moments both from the photos and words, but also through the ideas and approaches of the photographers themselves.” —TP