The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery presents presidential wingmates.

Twenty-one-year-old Abigail Powers had just begun a full-time teaching career in upstate New York when she met 19-year-old Millard Fillmore, an older student who was barely able to read. Soon they were falling in love, and when Fillmore’s family relocated they kept up a correspondence. They eventually reunited and married in 1826, seven years after first meeting and more than two decades before Fillmore became the nation’s 13th president. During her time in the White House, Abigail continued her interest in lifelong learning, installing a reference library in the mansion and inviting authors like Charles Dickens and Washington Irving to visit. Less than a month after Fillmore left office, she died of pneumonia.

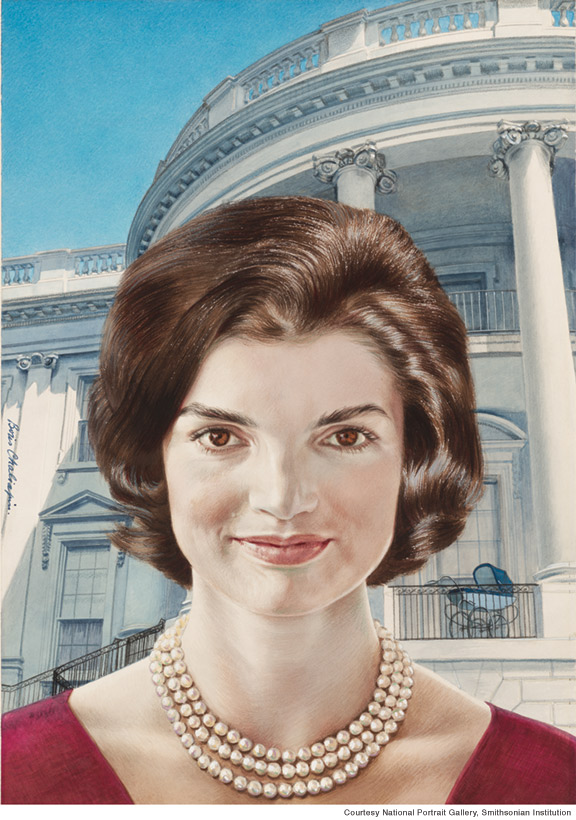

It’s a safe guess that most living Americans haven’t retained all that much historical knowledge about Fillmore, and it’s an even surer bet that we know less about his wife. The same could be true of women like fashionable Frances Cleveland, the young bride who joined the president while he was already in office and quickly became the Jackie Kennedy of her time. Or Helen Taft, the first presidential wife to ride with her husband during the inaugural parade. Or Caroline Harrison, who established the presidential china collection, initiated a restoration of the mansion, and most significantly, raised funds to create the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine on the condition that it open enrollment to women. Other first ladies, of course, have more decidedly etched themselves into the national memory, starting (almost) from day one when Abigail Adams implored her husband, John, to “remember the ladies.”

“This group is filled with bright, ambitious women,” says Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, the Class of 1940 Bicentennial Term Associate Professor of History of Art, who curated Every Eye Is Upon Me: First Ladies of the United States for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery (scheduled to be on exhibit through May 23 and available online at firstladies.si.edu). The exhibition’s title comes from a letter Julia Gardiner Tyler wrote to her mother after she became the first woman to marry a sitting president. Shaw adds, “I think it’s fair to say that many of them were smarter than their husbands.”

Shaw, whose research and teaching often emphasizes portraiture, says that she “wanted to focus on what made each of these women’s lives singular and to examine their portraits for hints at the way she presented herself.” As an example, she cites Ida McKinley, who suffered from terrible seizures. “In the miniature watercolor we have on exhibit, she’s in profile offering a view of her cropped hair,” says the historian. “It’s a style she wore on the recommendation of doctors who believed that long, heavy hair constrained the cranial nerves. And so she’s owning her disability. She’s basically saying, No, I don’t have a huge bun of hair back here. This is how I look. I was, like, wow, we can really get a sense of her strong attitude through this portrait.”

Another of the curator’s favorites is a reproduction of a sepia-toned, hand-tinted albumen silver print of Nell Arthur in which she wears a double-strand pearl necklace. Less than a year before her husband, Chester A. Arthur, was elected vice president, she died of pneumonia; after Arthur became president, he kept the photograph on his nightstand at the White House. “Some of these portraits are quite intimate,” Shaw observes. “There are so many great love stories and family memories associated with them.”

Other standouts are dramatically larger, including a trio of full-length depictions in oil. In one, Lucy Hayes stands regally draped in a crimson velvet gown. “It just blew me away when I saw it installed,” says Shaw. “It reminds you of how infrequently we see women portrayed so boldly.” The assemblage consists mainly of oils on canvas (including works by a few well-known names like Thomas Sully and Cecilia Beaux), but it also features photographs (including of Mary Todd Lincoln, since no verified painted portraits of her survive), watercolor miniatures on ivory, works on paper, and one marble bust. The latter is of Harriet Johnston, one of several women presented who were not spouses of a president; in this case Johnston served as first lady for her bachelor uncle James Buchanan.

The exhibition is the result of Shaw’s recent 18-month stint as senior historian and director of research, publications, and scholarly programs for the gallery. In addition to tracking down the 60 or so pieces (depicting 55 women) that appear in the show, Shaw also produced a companion book. Most of the works were drawn from the collection of the Portrait Gallery, but a dozen are on loan from the White House and several are from other libraries, including the National First Ladies Library in Canton, Ohio. “I was really surprised by how small it is,” Shaw says of that last. “It’s like a high school library. And when you think it’s for all of the first ladies—what a contrast to how each president gets his own huge, architect-designed library.” Even this small nod to the significance of first ladies didn’t exist, however, until Hillary Clinton helped bring the idea of a First Ladies National Historic Site to fruition. (See www.firstladies.org/libraryobjective.aspx for more.)

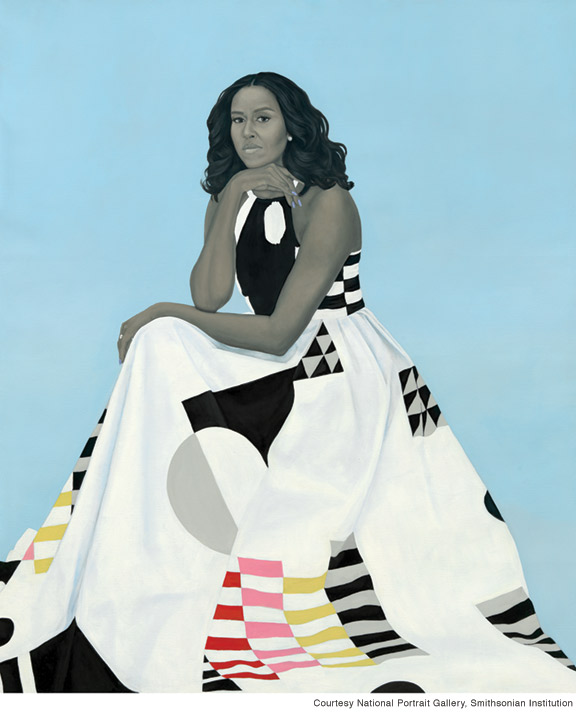

Incidentally, Clinton was the first presidential spouse to pose, in 2006, for a portrait commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery. (The National Portrait Gallery didn’t actually begin commissioning portraits until 1994, after George H. W. Bush left office.) It’s not surprising that when such recognition came, it began with Clinton, since no prior presidential spouse had been as involved in the day-to-day activities of the administration. But as one section of the exhibition notes, by the mid-20th century first ladies were clearly expected to advocate for issues they were passionate about.

Via her prolific writing and public speaking, Eleanor Roosevelt, depicted in a multi-portrait in poses that include thinking, writing, knitting, and removing her glasses, was the first presidential spouse to develop her own activist platforms. Later, Betty Ford (portrayed wearing a vivid blue top that echoes her cerulean eyes) gained attention for her advocacy for abortion rights and ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, and Nancy Reagan (adorned in her signature red) famously encouraged Americans to “Just Say No” to illegal drugs.

The gig continues to evolve. For instance, the current first lady, Jill Biden, is the first who has chosen to keep her day job (as a college professor). And as we inch closer to a first gentleman (see Douglas Emhoff, our first “second gentleman”), chances are we’ll be in for some more changes. “That individual will have to decide how he spends his unpaid labor and uses his bully pulpit, just as the women before him have,” says Shaw. “But I think the things we focus on will be different. We’ll be looking for other clues to his personality in a portrait—since not so much will be conveyed by appearance and clothing and hairstyles.”

—JoAnn Greco