As a scholarly paper, “The Paradox of Declining Female Happiness” doesn’t claim to offer any easy answers. But it certainly raises some interesting questions.

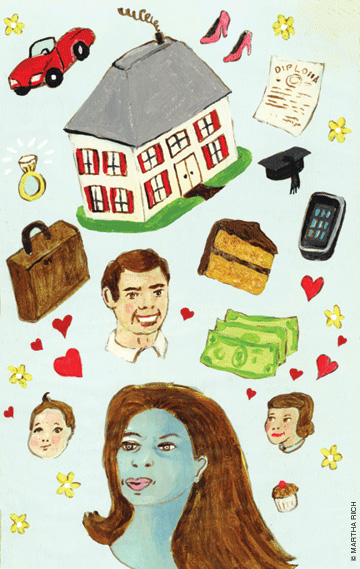

Written by Betsey Stevenson, assistant professor of business and public policy, and Justin Wolfers, associate professor of business and public policy, the paper examines a conundrum: that over the past 35 years, despite undeniable gains in a broad range of categories, “women in the United States have become less happy, both absolutely and relative to men.” Women’s relative subjective well-being, they add, “has fallen over a period in which most objective measures point to robust improvements in their opportunities.”

Even more puzzling is that the decline “is ubiquitous, and holds for both working and stay-at-home mothers, for those married and divorced, for the old and the young, and across the education distribution.”

Stevenson and Wolfers, who are not only colleagues but longstanding romantic partners who recently had their first child, have written on the subject of happiness before. Among their findings was the not-so-paradoxical phenomenon that in the U.S. and elsewhere, richer people are, on average, happier than poorer.

“But if you look in the U.S., what we’ve found is over the last 35 years, despite having gotten wealthier, the population hasn’t gotten any happier,” says Stevenson. “We found when we dug into it that actually men have gotten a little bit more happy; it’s the women who’ve gotten less happy. And that made us wonder what’s causing this.

“Economists would say that an increase in choices, opportunities, and rights should make you better off,” she adds. “And therefore what we would have expected to see is women getting happier. If the rights of women that have been gained over the last 35 years have come at the expense of men, we would have expected to see women becoming happier relative to men. Instead what we saw was the exact opposite.”

Forget the easy explanations. “Ross Douthat at The New York Times wrote an op-ed column that this is all about the rise in single-parenthood,” Stevenson notes, an argument that “doesn’t make any sense, given that these declines are found among married people, among single people, among people with kids, among people without kids, among young teenage girls, among older women.”

Nor does it have to do with the decline in the U.S. marriage rate, or changes in the divorce rate (which, contrary to popular perception, has fallen over the past three decades). “We don’t see this happening more in divorced people than among married people. Or among never-married people,” Stevenson says. “We’re unable to find any statistically significant differences among these groups.”

While men may well be the beneficiaries of the women’s movement, the “second-shift” theory—that women are unhappy because they’re burned out by the dual pressures of a professional career and family responsibilities—is not borne out by the data, Stevenson and Wolfers write.

“The decreases in happiness arising due to the ‘second shift’ should impact working mothers more than others,” they note. “Similarly, declines in happiness stemming from the challenges of single-parenthood should have greater impact on non-white women and white women with less education. Yet, we find no evidence of such differential changes in reported well-being.”

While women of all education groups have become less happy over time, the study notes, the declines in happiness have been “steepest among those with some college.”

At this point, you have to wonder: How important is happiness, anyway?

“That’s a really important question,” Stevenson says. “I would urge caution before we start jumping on the bandwagon of using happiness as a metric for evaluating public policies.”

A case in point lies in the comparison between 12th-grade girls and boys. The data “suggest that young men have become increasingly happy, while young women have become slightly less happy,” the paper notes. Yet by many metrics, girls are more successful in school these days—judging by the rising numbers of female college students, graduation rates, class rank, and other markers.

“It’s certainly a puzzle,” says Stevenson. “We see girls outpacing boys at rates that are close to two-to-one” across a range of academic measures. “It looks like the boys are happy to not have pressure on them.

“The question is, are they really better off?” she asks. “Is the good life to not feel that you have to achieve on all these different levels? And I think that it’s really an open question.

“I found the teenage-girl stuff the most fascinating stuff we looked at, because they gave a very clear message. What they think is important now spans community, family, and professional work obligations and achievements, and what they’re crowding out is time for fun—time for leisure, time for themselves.” As she and Wolfers note in their paper, even the proportion of young women reporting satisfaction with “friends and people you spend time with” has declined substantially.

“This is a refrain we hear all the time when we’re looking at a woman in her mid-30s to mid-40s who’s balancing career and kids, and she’s harried,” Stevenson adds. “But I found it really striking that this is also what’s happening among 17-year-old girls, who feel they need to compete, compete, compete. It may be that we have a very competitive society, so when girls start to achieve, this is the cost; it could be that happiness just isn’t a very good holistic measure; or it could be that girls are not in a good equilibrium right now, and they have to figure out that balance, which they haven’t done yet.”

Equally striking is that the girls “were really elevating this third thing: being a leader in their community—this idea that there is something besides your insular family and your professional life, there’s also the broader community and your obligation to that. And when I talk to female MBA students, I hear the same thing from them. They feel an obligation to give back somehow, to have a positive influence in the community.”

A number of similar trends are evident across the industrialized nations of Europe and Japan, but there are significant differences, says Stevenson. “Europeans have gotten happier as they’ve gotten richer, and the Americans haven’t, and it’s interesting to see that there has been an even more negative effect for women, particularly at a time when women are expected to be happier, because life has improved for them.”

Though she and Wolfers “would love to look at developing countries,” she says, so far they have lacked access to the kind of consistently collected data available from industrialized nations. But that will soon change. For the past several years, Gallup has been polling people in 140 countries about their subjective well-being. “In another five or six years we’re going to have a decade’s worth of trends across almost every country in the world, and I think we’ll be able to say a lot more at that point.”

Stay tuned.

—S.H.