It’s been almost a quarter of a century since the last freight train rumbled along the High Line. Built in the 1930s, its elevated tracks were designed to keep trains off the streets of Manhattan and send them directly to the city’s factories, where they would unload raw materials and load the finished goods. Now, the hulking, 1.45-mile structure slices across the West Side landscape like an industrial dream gone to seed, from 34th Street near the Hudson River through West Chelsea to Gansevoort Street in the Meat Packing District.

For years, Joshua David C’84 lived in the shadow of the High Line without really noticing it. He was a freelance writer then, and it wasn’t until he began working on an article about his own West Chelsea neighborhood that the abandoned structure began to register in his consciousness.

“It was one-and-a-half miles long, seven acres waiting to be used, just an amazing environment that nobody had ever really seen,” David recalls. “It caught my interest and made me want to move forward with the project.”

That “project” involved converting the High Line into a long, thin, elevated city park, and in 1999 David and Robert Hammond took the first big step toward making it happen. They co-founded the Friends of the High Line (FHL), a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to the “preservation and reuse” of the old structure, which is owned by CSX Transportation.

David and Hammond knew they had their work cut out for them. A group called the Chelsea Property Owners, which owns the real estate beneath the structure and believes that their property values would rise if the High Line were demolished, had won a Conditional Demolition Order from the federal Surface Transportation Board in 1992. Since then, the wrecking ball had moved even closer.

“When Robert and I and the Friends of the High Line entered the stage, there was already a fair amount of legal history on the structure,” says David. “The movement was pretty much in motion to tear it down. The Giuliani administration supported tearing it down, and nobody was standing up for it.

“We started with a list of priorities that included creating open space, historic preservation, great design, community-based planning, and economic development,” he explained this past February to a group of Penn Praxis students, who were hoping to apply some of his experience to a similar project in Philadelphia. (That would be the Reading Viaduct, a half-mile stretch of abandoned raised tracks that runs northeast from the old Reading Terminal.) “The idea that a structure like this, turned into a public open space, could become the spine of a vibrant urban district is very important to our work.”

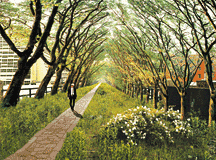

Both the High Line and the Reading Viaduct have a highly successful model to draw on: the Promenade Plantée in Paris—a former railroad viaduct that was transformed into a city park in the early 1990s. According to the FHL’s website (www.thehighline.org), the Promenade Plantée “has helped to revitalize the 12th arrondissement” and “acted as a catalyst for economic development.”

To examine the economic feasibility of the High Line project, the FHL commissioned the consulting firm of Hamilton Rabinovitz & Alschuler, which found that converting the High Line to public space was not only technically and legally feasible but also “economically rational.” In other words, future revenues generated by converting the High Line into a public park would be equal to or greater than the cost of creating it.

“Parks and open space add value to adjoining areas, and by adding value, they increase revenues generated in the adjoining areas,” explains David. “The leading example is Central Park. It created such massive new revenues from property taxes around the park that it very quickly paid back the investment. Central Park is an unusual case, but our study looked at a number of other small pocket and linear parks that increased property values at significant rates.

“We also looked at the value created by defining a new, marketable neighborhood in New York City,” he adds. “We’re essentially saying that the properties around the High Line would be more valuable through identification with that public space. That theory has begun to play out already.”

In March 2002 the FHT won a significant victory when the New York State Supreme Court ruled that the city had acted illegally in signing a demolition agreement. (That ruling was later overturned, though the FHT has filed a notice to appeal the decision that reversed their original victory.) Later that year the City of New York formally endorsed the High Line project and petitioned the federal government to transform the High Line into an elevated walkway.

Two months ago, the FHL and the city formally kicked off the process for choosing a design team that will create a master plan for the High Line’s conversion to public open space. The winning design team will be announced during the summer.

“Structures like the High Line and the Reading Viaduct have a lot of memory associated with them,” David adds. “They’re monumental bones of railroads, the grand railroads of our past that form a really integral part of the memory of our cities.”

—S.H.