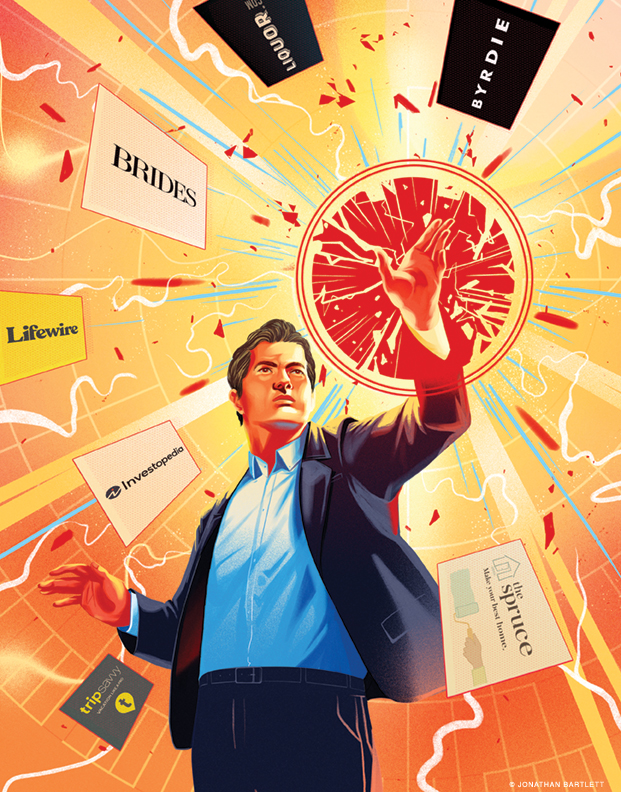

After putting the familiar but failing website About.com out of its misery, Dotdash CEO Neil Vogel has managed to craft a thriving group of websites from the company’s wreckage.

BY ALYSON KRUEGER | Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

One day in 2016 Neil Vogel W’92 marched into the executive offices of media company IAC and announced, “I want to blow the whole thing up.”

For three years, Vogel had been at the helm of the website About.com, which IAC—whose “family” of 150-plus brands and products also includes digital platforms like Vimeo, Tinder, and Angie’s List—had bought from the New York Times in 2012. Behind its red circle logo, About.com published a bewildering variety of “need-to-know” content. Readers went there to learn about everything from the symptoms of diabetes to how to perfectly barbecue chicken. While some of the information was undoubtedly valuable, the website itself was archaic, slow, and hampered with ads.

“It was this weird, broken, ad-supported thing that was just on the internet,” remembers Vogel. “I had a friend who called it ‘the back button’ because it was so outdated.”

By 2016, Vogel had already tried pretty much everything he could to restore About.com to relevance. He made it prettier, quicker, more user-friendly. He tried publishing more content with the potential to go viral. But the audience kept declining. He missed his target numbers for nine straight quarters. Every time, he would approach the head honchos at IAC, “and explain in great detail why our great ideas weren’t working,” he says. “The fact that we were still employed was unbelievable.”

People who work in digital media know the industry has few second acts. “Internet media companies rise and fall, and they don’t come back,” says Aaron Cohen, a veteran of multiple start-ups who teaches courses on digital media at New York University. “Yahoo is a good example. So is Myspace and Friendster. Companies have their moment, and then they fade.”

Still wanting to try to beat those odds, however, Vogel came up with a final plan—that is, blowing the whole thing up.

He would stop trying to resuscitate About.com. People didn’t want large, catchall sites anymore. Rather, he would save the strong content and divide it into websites that focused on one topic like health or tech. Each website would have a brand that he would develop from scratch. The name About.com would get thrown away. “The fact that he was willing to creatively destruct About.com, that was really unusual,” says Cohen. “The best asset About.com had was its name. It was a signature internet brand.”

While most digital media companies at the time were focusing on producing fun, newsy content to attract readers, Vogel decided his sites would focus on straightforward, service-oriented articles written by experts that readers would find helpful today or in 10 years. The websites would also load at “lightning speed” and have two-thirds fewer ads than competitors to improve user experience, thereby increasing the engagement and size of the audience—making it that much more attractive and valuable to advertisers.

“We are going to reinvent publishing on the internet,” he says, recalling his pitch to his bosses. “Oh, and by the way, I know I just missed numbers for nine straight quarters, but I need 30 million bucks to do it.”

“I don’t know if terrifying is the right word for that meeting,” says Mark Stein C’90 W’90, IAC’s executive vice president and chief strategy officer. “But we had to have confidence in him, that’s for sure.”

About.com was renamed Dotdash (the dot was taken from aboutdotcom, and the dash in Morse code is the letter A). Different brands such as The Spruce (home), Verywell (health), TripSavvy (travel), Investopedia (financial management), and more were launched under that umbrella name. The transition was rough—the company lost $20 million in 2016—but by 2019 it was making $40 million and getting hundreds of millions of readers a month.

While other digital media companies are getting smaller, Dotdash is expanding. In May 2019 it purchased Brides from Conde Nast, ending the magazine’s print edition, which had been losing readers steadily, and shifting to digital-only publication. “Those about to walk down the aisle these days are more likely to browse wedding sites or scroll through Instagram than run to a newsstand,” wrote the New York Times in an article about the acquisition. And while companies such as BuzzFeed and Vox Media went through massive layoffs last year, Dotdash has been ramping up hiring, with plans as of early in the year to add 1,500 people in 2020, bringing their total number of employees to around 1,950.

Most telling, says Max Willens, a senior reporter at the online-media trade publication Digiday, is that other brands are starting to mimic Dotdash’s strategies. “Folks in the media have noticed how much success Neil has had,” he says. “SEO and search strategy, what Dotdash focuses on, is the new hot thing again.”

As Willens puts it, 20 years ago search was the dominant audience acquisition strategy. That meant media companies got their audiences by showing up in search engines such as Yahoo and Google. To do that they had to not only write content that answered the questions people were asking; they also had to have the correct headlines, photos, and blurbs that people wanted to see. That’s how SEO, or search optimization strategy, was developed. SEO is the process of increasing traffic to a site by becoming more attractive to a search engine.

Around 10 years ago, however, there was a shift. As millions of people flocked to social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, and then Instagram, media companies thought that they could attract an audience by having ordinary people share their content among their networks. The idea behind this social strategy was that, if content was so attractive to people that they all shared it, it would go viral and generate more traffic.

Now, however, companies are realizing that a social strategy is fraught with challenges, Willens says. “On Facebook it can be difficult to tell what people will respond to, like what will go viral,” while analyzing search was more straightforward. “You can tell what kind of demand there is. You can just look at Google search trends, and you can tell the price for certain keywords if you are trying to buy an audience. You can tell how much interest there is around this stuff.” Which is why more companies, even ones that have traditionally relied on social, are turning to a search strategy, and the reason Vogel never left.

Of course, this kind of imitation also means Dotdash will have to try even harder to stay ahead of its competitors. “Netflix may be a good company, but now they have HBO Now, Disney+, Apple TV,” says Cohen, drawing an analogy to the streaming wars now heating up. “Their competitive landscape is changing even though they’ve arrived.”

“There is a real Philadelphia-ness to him,” says Cohen, describing Vogel’s personality. (The two crossed paths in the 1990s in digital media’s early days, and more recently Vogel spoke to Cohen’s class at NYU.)

In April Vogel joined the 10-member board of the Philadelphia Inquirer and was quoted as saying that he “essentially learned to read” from the paper’s sports section and remains a subscriber. He holds meetings in a conference room decorated with Eagles banners and pillows. After the Eagles’ 2018 Super Bowl victory over the New England Patriots, Philly-style cheesesteaks were delivered to Dotdash’s midtown Manhattan office for the entire staff—paid for by Tim Quinn, Dotdash’s CFO and a Pats fan, as part of a bet.

Vogel loved his city, but he felt stifled by the suburban public school he attended. “It wasn’t far off from The Breakfast Club,” he says. “If you were smart, you were one thing. If you liked sports, it was another. If you partied, it was that. It wasn’t all that appealing to me because I liked sports, but I also liked getting good grades.”

He applied Early Decision to Penn because one of his friends’ older brothers had gone there and wasn’t defined by a category. “I learned from him that you could like school and politics and drinking beer and sports and doing dumb things,” Vogel says. “I was like, ‘These are my people. I can be a whole person around them.’”

Vogel adjusted to Penn life quickly. He joined the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity, where he thrived as social chair. According to Andy Snyder W’92, a former roommate of Vogel’s who is now CEO of the investment management firm Cambridge Information Group, everyone wanted to be his friend. “He was somebody people wanted to be around, a fun guy,” he says. He also offers a (possibly facetious) theory about Vogel’s chosen career path. “He was always about 10 years behind us in maturity, which is probably why he was in touch with the wave of the internet sooner than us.”

The internet is still new enough that there are those like Vogel who have been around it since the beginning.

In the mid 1990s, after working 80-hour weeks for an investment bank, he joined Alloy, a company that was marketing apparel and accessories to teenagers through catalogs—and wanted to start using the internet. (It’s hard to imagine now, but that idea received pushback, says Vogel. “People were like, ‘No kid would buy anything online, because they don’t have credit cards.’”)

Vogel was in charge of business development. In the dot-com bubble, the company soared. “The world was going insane, and we went public in 1999,” he says. “We must have had less than 30 employees and were losing money and all of a sudden we had all this capital.” (Fortunately, Alloy executives invested that money in cash-flowing businesses, so they didn’t go bust like many others when the bubble burst in 2001.)

In 2003, Vogel took a spring and summer off. “I was cooked. I needed a break,” he says. “There were a lot of hours in banking, and a lot of hours at Alloy, and they all stacked up together.” He bought an old Ford Bronco and did everything and anything that sounded fun. “I lived at the beach for a couple of months,” he recalls. “I went mountain biking. I went to Europe. I was a photographer’s assistant for a month. I was open for any idea.”

At the end of the summer, he “got properly bored, which was the goal,” he adds. So when an old boss suggested, as his next media venture, to manage various awards shows, he said yes. His first purchase was the Telly Awards, a Kentucky-based awards program for local television shows and commercials. The program had a large network of nominees but had failed to stay relevant in the digital age. At the time, applications were all by mail-in ballot, and there were no online announcements of winners or online advertising associated with the awards. Vogel took it online, refreshed the branding, and increased the number of participants paying to enter. Soon his company, Recognition Media, owned eight different awards shows including Internet Week in London and New York.

“What we learned, the hook of the business, is that everyone needs measurement in their work product,” Vogel says. “If you are a real estate broker, you either sell houses or you don’t. But if you make television commercials or websites, you need third-party validation for your subjective work. To get this, people are able to spend their company’s money for tremendous personal gain.”

One of Vogel’s signature acquisitions was the Webby Awards, essentially the Oscars for the internet. In 2005, the first year Vogel ran it, Al Gore won the lifetime achievement award. Per award rules, the former vice president and 2000 Democratic presidential candidate had to give a five-word acceptance speech. His message, “Please Don’t Recount This Vote,” went viral “before anything went viral,” says Vogel. “A friend saw it on CNN in the airport in Israel. That really helped us, and the business went nuts.”

The following year, Prince won the same award and provided another viral moment. He showed up at the last minute, sang a song he made up, smashed a $15,000 guitar on stage, and then left. Vogel still cracks up as he remembers the late musician’s bodyguards trying to ensure the episode wouldn’t show up online: “We were like, ‘Yeah, OK, guys.’”

(While Vogel stepped down from his role as founder and CEO in 2013, he is still on the company’s board. That means no one at Dotdash can receive a Webby. “It’s killing me,” he says.)

When Joey Levin EAS’01 W’01, who is now the CEO of IAC and also knew Vogel from Penn, called to ask his thoughts on About.com shortly after IAC acquired the company, Vogel responded snarkily: “I don’t think about About.com.” Still, he promised Levin he would look into the brand.

Slowly Vogel started to see potential. Some 40 million people a month were still using the site. It published two million pieces of content, some of which was compelling. “I liked that the content helped people,” he says. “It wasn’t like, ‘Here are 10 ways you know you live in Chicago.’ It was useful stuff.”

He also realized the possibilities for advertising. “You knew someone was into barbecuing because they were reading about how to do it,” he says. This fact stood in contrast to other sites where, for example, you had to guess that someone might be looking for new makeup because they were reading about the best dressed celebrities at the Met Gala.

After multiple rounds of interviews—“I wouldn’t say it was easy to recruit him; he’s too smart of a person to make it completely easy,” Stein says—Vogel agreed to run About.com, figuring he couldn’t make it any worse. “The site was so bad, I was like, ‘OK, I’m not going to be the guy who messes it up,’” he says.

Digiday’s Willens says that one of the most challenging parts of Vogel’s eventual decision to abandon the About.com name is that it is very difficult to build new brands on the internet and get people to care about them. “It’s not something you can do overnight,” he says. But now, four years later, there are signs that Dotdash’s sites are thriving.

Verywell Health, a website that provides wellness information written by health professionals, was one of the first brands Dotdash launched out of the ashes of About.com in April 2016. In February the website launched its first “Champions of Wellness Awards” acknowledging health professionals in 100 different categories. “This is proof that the brand is working,” says Willens. “If no one knew what Verywell was, no one would care that they got an award or enter the nomination process.” High profile winners include actress Jameela Jamil for her work on “body positivity” and neurosurgeon and CNN chief medical correspondent Sanjay Gupta.

One of Dotdash’s largest brands is its home site, The Spruce. It attracts 30 million users each month and has 14,000 pieces of content, such as “The Surprising Places You’re Forgetting to Clean” and “Cheery Yellow Paint Colors for Any Room in Your Home.” A sign their brand is working, says Willens, is that they have started doing product licensing. Specifically, they launched 32 interior paints, made by KILZ, that were designed by The Spruce editors. “They had to offer demonstrable proof to a company like KILZ that people know what The Spruce is and that they trust it,” he says. “Would you buy something based on the recommendations from any random website?”

Of course, for these brands to succeed, the company has to drive readers to its websites.

Vogel explains there are three reasons people use the internet. One is social, to connect with others. That is where brands like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter thrive. The second, to get information they want to know: sports scores, celebrity gossip, news. The third category, in which Dotdash plays, is to secure need-to-know information. My iPhone screen cracked, what do I do? What do I wear to a funeral?

The company relies on Google and other search engines to lead people to its sites after they type a question. “They take great care to ensure their pages are built in a way that Google’s search algorithm likes,” says Willens. “Dotdash has an entire team to decide the best titles, how many images should be on a post, what advertisements should appear on the site and how they load.”

In some ways it’s an easier strategy than social, where companies lean on readers to share content. But there is also a downside, says Willens. “You are pinning your fortunes around the whim of one company, Google.” As the biggest name in search, Google can send companies scrambling to respond to periodic updates of the search algorithms that govern results—to avoid getting pushed down below the front page.

Vogel believes as long as his articles are clean, written by experts, and provide the information people want, there is no reason Google wouldn’t highlight them. It’s also telling that companies like BuzzFeed are starting to focus on search as well, says Willens. Business Insider, for example, has started writing how-to articles like how to set up a Roku player.

Cohen worries the company is missing an opportunity to grow by shying away from social strategies. “Dotdash wants to get its content in front of as many of the right people as it can,” he says. “And Instagram is an important source of distribution the same way Google is.” Currently there is a slim chance a reader will stumble upon an article produced by Dotdash if he or she is not looking for it.

He also worries about Dotdash’s vast challenge of keeping all of its need-to-know content updated. “It requires a lot to stay up to date in areas like savings, taxes, and accounting,” he says. “Dotdash has figured out a way to do it, but as they grow it’s going to be hard.”

“If the government puts out a new nutrition warning about jelly beans tomorrow, we have to find all of our jelly bean content across all of our verticals and update it right away,” says Vogel. But that is an age-old journalism problem, he adds. “If a political story breaks on Christmas Eve, the Washington Post has to deal with that also.”

The clearest indicator of Vogel’s success is that advertisers seem to approve. For eight straight quarters, 18 of the company’s top 20 advertisers have returned.

Vogel says that is because the company knows exactly what people are reading, so he can target ads to them. “If you are a gluten-free food company, and you want to advertise your new pasta, we can put it on all of our recipes for pasta and all our posts about celiac disease and all of our articles about health trends,” he says. “That is way better than putting it on a random website.”

Dotdash is currently on a buying spree, so it can offer more verticals for advertisements. In the past two years the company has scooped up Byrdie (beauty), Brides (weddings), Liquor.com (alcohol), Mydomain (lifestyle), Investopedia (finance), and TreeHugger (green living), among other brands.

Vogel’s plan is simple. Create more evergreen, need-to-know content in the categories Dotdash already has, as well as in new categories where Dotdash hasn’t yet ventured.

“Verywell is still 25 percent of the size of WebMD. The Spruce is one-fifth of the size of Allrecipes. Our brands are still so new; they need to grow,” says Vogel. “I know I sound really boring and really cliched. But make great stuff, and people will come, and you won’t have any problems.”

Alyson Krueger C’07 writes frequently for the Gazette.

Another untapped platform for dotdash might be teaching or education related. I could see articles like Verywell has on health being written about reading or math strategies or behavior strategies in the classroom for teachers. All research based but conversational as the dotdash articles are.