Mixing up-to-the-minute marketing techniques, tried-and-true entertainment formulas, and engaging young stars and stories, Disney Channels Worldwide President Richard Ross C’83 is helping ensure that the company remains supreme in the kid-entertainment universe.

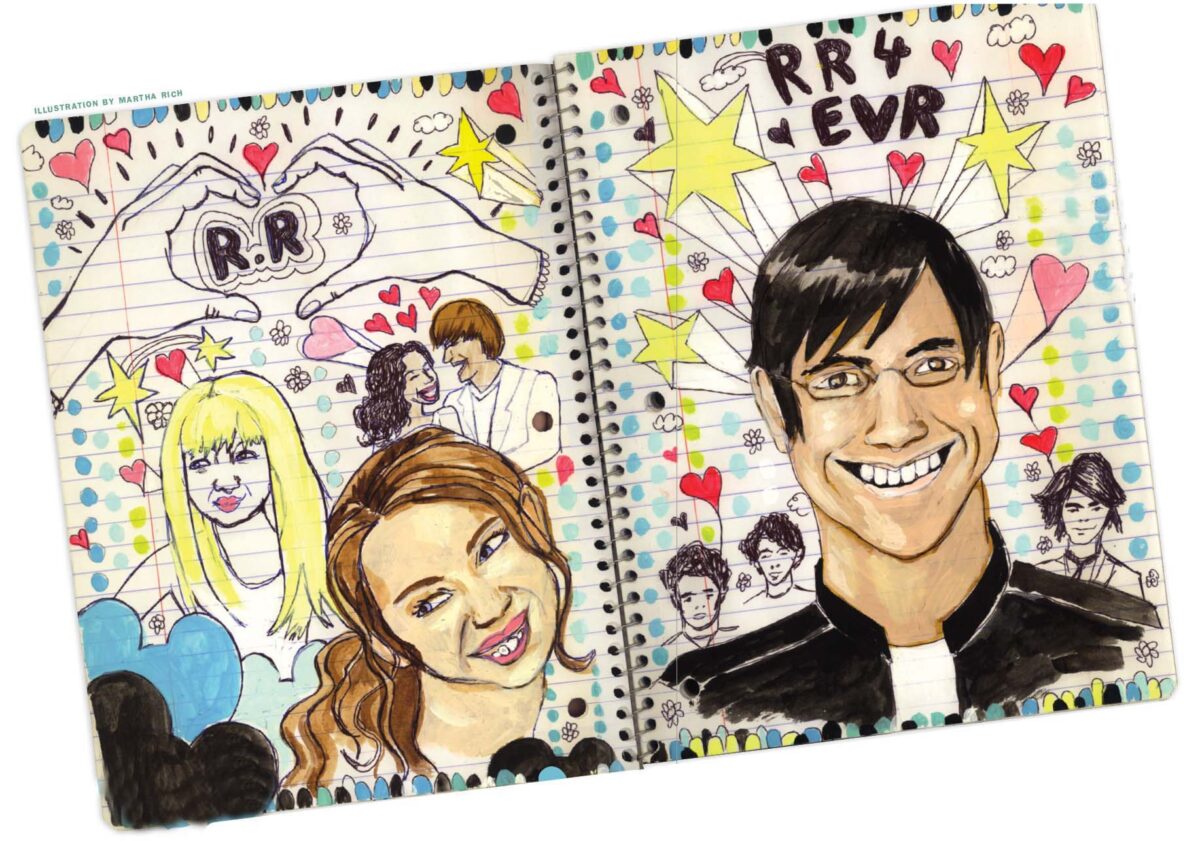

By Robert Strauss | Illustration by Martha Rich

Sidebar | Living in Disney (Channel) World

In her popular Disney Channel cable television show, Hannah Montana (if you live anywhere in the vicinity of a nine-year-old girl, you have surely seen it), Miley Cyrus plays a teenager with two identities—one as a famous rock star and the other as the daughter of a single father just trying to make it through what passes on TV for a normal life. Miley Stewart (Cyrus’s regular-girl identity) and her wacky older brother Jackson live in a Malibu beach house with their widowed father, played by Cyrus’s real-life father Billy Ray Cyrus, previously best known for his 1990s-era country music hit “Achy Breaky Heart.” The show’s comedy is a cheerful mix of teen misunderstandings and I Love Lucy slapstick revolving around Miley’s halfhearted efforts to keep her identities separate, with plenty of time left over for “Hannah” to perform her latest hit.

Since premiering on the Disney Channel in March 2006, the series has become a consistent top-rated show (a new episode was the most watched cable show in primetime for the week ending July 5). It’s also spawned hit albums, sold-out live shows and a concert film, a successful theatrical film release this past spring, and an avalanche of branded merchandise—everything from dolls to dried fruit.

Hannah Montana is just the latest example of the Walt Disney Company’s uncanny ability over much of the past century—from the dawn of sound film to the Internet age—to anticipate what kids and teenagers will watch and get enthused by. Having set the standard in theatrical movies and broadcast television, the company has in recent years worked its magic in the burgeoning cable-TV universe, packaging enduring formulas in up-to-the-minute wrapping, and supplying a steady stream of new faces to replace inevitably aging favorites.

For readers of a certain age, the show’s twinning device may recall the 1961 movie The Parent Trap, starring Hayley Mills (or its 1998 remake with a pre-tabloid Lindsay Lohan) in the dual role of sisters separated as infants and raised by their divorced parents, unaware of each other’s existence until they meet at summer camp, switch identities to get a taste of each other’s lives, and eventually engineer their parents’ reunion.

Going back even further, the essential DNA of Disney’s 1950 dreams-come-true classic Cinderella is faintly recognizable in Hannah Montana—though the differences are more telling. No housework, for one thing, and the dream-come-true isn’t a royal marriage anymore but personal empowerment in a life that combines worldwide fame with hometown friends (the “best of both worlds,” as the show’s infectious theme song puts it).

“Disney always seems to find the next star, the next thing. They have found young stars who are almost preternaturally magnetic to young adolescents or old elementary schoolers,” says Jonathan Storm, longtime TV critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer. “In TV, because they throw so many wads of wet paper to the wall, some will stick. But to get such a run as Disney, and now the Disney Channel, has had, that guy Ross must be doing something right.”

“That guy Ross” is Richard Ross C’83, president of Disney Channels Worldwide since April 2004, and an executive with the company since 1996. In his current role, Ross oversees 94 channels available in 163 countries in 32 languages, along with their associated websites, as well as Radio Disney, which is available on 50 stations, satellite radio, iTunes, and mobile phones.

One of those channels, Playhouse Disney, caters to the traditional audience of very young children, introducing the preschool set to the familiar cast of Disney characters in shows like Mickey Mouse Clubhouse and offering newer animated fare like Little Einsteins (four kids and their rocket ship, whose adventures promote art and music appreciation) and Handy Manny, which spotlights Latino culture. But where Ross has really made his mark is at the flagship Disney Channel, aimed at a somewhat older demographic of kids aged 6-14. During his tenure, the channel’s core audience of “tween” girls (ages 9-14) has ruled large swathes of pop culture, generating top-grossing albums, movies, and TV shows, while consuming an astonishing array of associated merchandise featuring their favorites.

Besides the Hannah Montana phenomenon, Ross has launched the Jonas Brothers—boy-band heartthrobs Kevin, Joe, and Nick, with their own concert movie and Disney Channel TV series—and, above all, has shepherded the megahit franchise High School Musical, now at three movies and counting.

Ross presides over something that is both a legacy and a modern marketing-entertainment phenomenon. Disney has immediate name recognition for parents and children, and the Disney Channel is both its primary source of programming and main arm of promotion. The relationship between the two functions is seamless.

Commercial breaks are mostly ads for its own upcoming TV series and original movies, as well as Disney theatrical-film releases, music, theme park visits, and other spin-off products and merchandise. The stars frequently appear in on-air promos, public service announcements, and a variety of between-show interview segments designed to give viewers an “inside look” and promote a sense of community, as if the casts of the various shows and the audience are one big family. This idea is reinforced by the Disney Channel website, where fans can watch more promotions, see video clips and TV episodes, participate in surveys and contests, play games, download photos and screensavers, and send emails that stream on the screen.

To heighten the close-knit atmosphere even further, the Disney Channel also does occasional “mashups” of shows, in which various casts spill into each other’s universes. In one that premiered over the summer Miley and her friends from Hannah Montana find themselves on a cruise ship, the S.S. Tipton, the setting for a series called Suite Life on Deck, starring twins Cole and Dylan Sprouse (itself a spinoff from an earlier long-running show where the boys wreaked comic havoc in a posh hotel). Also along for the ride are the cast of The Wizards of Waverly Place, a kind of comic takeoff on Harry Potter that premiered in 2007, led by teenaged Selena Gomez. A video clip running on the Disney Channel website in advance of the show’s July 17 premiere had the actors enthusing over the opportunity to spend quality time with each other. “We all talk about how we’re all family and how we’re all friends, but you never get to see that,” says Miley in a typical comment. “So I think it’s cool that we get to share what we love together.”

Disney also grooms its stars as assiduously as any old-time studio. Also airing this summer was Princess Protection Program, co-starring Gomez and another rising star, Demi Lovato. (The two are BFFs—“best friends forever”—off-screen as well, according to any number of fan magazines and websites.) Lovato first came to fame in the 2008 Disney Channel movie Camp Rock, which also featured the Jonas Brothers. She has her own Disney Channel TV series, too, titled Sonny With a Chance. A Wizards of Waverly Place movie premiered over the summer as well, and Camp Rock II is scheduled for 2010.

But while Disney may be relentless in promoting its products and stars, it’s also true that much of the Disney Channel’s programming, particularly under Ross, has won praise for being among the best there is, especially for the hard-to-please market of young teens.

Even some adult critics can recognize its charms. While notices for High School Musical 3, for example, were mixed, Salon reviewer Stephanie Zacharek wrote that the film “offers simple, buoyant pleasures,” and asked, “Why wouldn’t kids like this?” She singled out for praise the “splashy, effervescent musical numbers,” reminiscent of the old Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland putting-on-a-show musicals, and allowed that the songs, while not particularly memorable, were no worse “than the faux-rock toodling of Rent.”

“Disney has hit it right,” says Derek Baine, an analyst for SNL Kagan, an entertainment research firm. “Ross has managed to find stars who kids relate to and vehicles, particularly High School Musical, that resonate with them. And he has found a way—through merchandising and music and sequels—to make the most out of the stars who are inevitably only around for a few years before moving on.”

Ross became focused on the entertainment business at just about the same age as the audience to which he now caters. He says he was never really a performer as a kid growing up in Eastchester, New York, just north of Manhattan. Instead, he was an entertainment industry fanatic, at age 12 asking his parents for a subscription to Daily Variety rather than Sports Illustrated like his friends. Watching TV while he did his homework, he paid attention to production values in between the canned laughs.

“He was always in the know about a lot of things in entertainment—more than anyone else,” says Marcia Goldstein C’83, who grew up with Ross in Eastchester and also was a classmate at Penn. “It seemed clear to all of us early on that that was where he was headed.”

Though his general aversion to performing continued at Penn, one exception was giving campus tours. “That was a great outlet,” Ross recalls. “You could tell stories. I loved getting to know everything about the school, so not only was I an expert, but I could be comfortable talking about it.”

At the same time, Ross displayed a budding entrepreneurial streak. In those pre-laptop days, he was among the few on campus who could speed-type—and was savvy enough to recognize a market opportunity. “He saw there was a service in West Philadelphia called Kirk, which typed papers for students, so he started one called Spock,” says another college friend, Wendy Cohen C’83. “He is one of the funniest people on Earth, so even when he was going to make a little money, he wanted to do it in a fun way.”

Ross majored in international relations, but he always had his eye on the entertainment industry as a career path. In what he calls a perfect example of “Jewish geography,” his mother knew someone from her summer camp who had a connection with the William Morris Agency in New York, which helped him land a summer internship there while he was at Penn. (“This was back in the day when the Xerox machines were the size of RVs and there was something called the secretarial pool,” Ross says.) It was the stereotypical start in the entertainment business, and Ross played his role as rising young man earnestly, taking on whatever job was necessary to learn all parts of the business and returning for several summers, even after enrolling at Fordham Law School following his graduation from Penn.

“I really only went to law school because I got out during a recession, and it seemed like a way to do something positive while waiting to get a job,” he explains. “My PhD, though, was working at William Morris. I learned just by being able to meet so many people there.”

After finishing law school in 1986, he got in on the ground floor of what was then still a new concept—a kid’s TV network, Nickelodeon. Early on there, he met a young executive named Anne Sweeney, who became his mentor. She didn’t exactly give him free rein, he says, but pushed him to be creative in business. For instance, he took a feature that could have been a dull sidelight—Nick News, moderated by former NBC reporter and newscaster Linda Ellerbee—and made it a lively, engaging syndicated show, one that not only impressed parents and educators but also attracted children.

Ross followed Sweeney to FX, one of the Fox networks, and then to Disney/ABC in 1996, when she was named president of the Disney Channel. His first job was as senior vice president overseeing programming and production. Later he was promoted to general manager and executive vice president, and then to Disney Channel president, succeeding Sweeney in the position. He took over Disney Channels Worldwide when she was promoted from that post to become co-chair of Disney Media Networks and president of the Disney/ABC Television Group in April 2004.

“There are several things that contribute to Rich’s success: his tremendous creativity, his constant curiosity, and his ability to imagine what could be,” says Sweeney. “But I think the key is his passion for what he does. It’s one of the first things I noticed when we originally worked together, and one of the many reasons hiring him immediately was a priority for me at Disney Channel.”

Though Ross didn’t set out to work in kids’ entertainment—he is in a long-term relationship but has no children of his own—he soon came to love it.

“Kids are incredibly authentic,” Ross says. “For one thing, they have a real understanding about television. They know what they like, and they say so right off. They don’t waste time with things they don’t like. So it is incredibly challenging, but really rewarding at the same time, to come up with something that really attracts the audience.”

When Ross joined Disney, the company’s cable operation was in the unusual position of having to play catch-up. Competitors like his former employer Nickelodeon and the Cartoon Network were stealing Disney’s animation thunder with series like Rugrats, Ren and Stimpy, The Powerpuff Girls, and Dexter’s Laboratory, and Nickelodeon had also created a kids’ comedy niche with the sketch-comedy show All That and programs that dumped green slime on performers—which remains a network signature.

The Disney Channel jumped in where those channels and other sources of children’s programming like Fox (whose shows tended to be boy- and action-oriented) and PBS (younger fare like Sesame Street and Barney) left an opening—with teenaged and pre-teen girls. The channel scored early successes with shows like Lizzie McGuire and That’s So Raven—starring Hilary Duff and former Cosby Show cast member Raven-Symoné, respectively—that were built around the travails of a teenaged girl and her friends, her generally befuddled parents, and her annoying younger brother, presaging the coming madness over Hannah Montana.

Under Ross, the Disney Channel has been the first or second highest-rated basic cable network for all viewers for the past three years; it’s been number one in primetime viewing among 6- to 11-year-olds for six years and 9- to 11-year-olds for eight years. Ross also was responsible for a string of successful TV movies produced for the Disney Channel, which have scored the highest ratings with those age groups for eight years running. High School Musical 2’s premiere in August 2007 was at the time the highest rated telecast in cable history with 18.6 million viewers.

Ross was also quick to sense the breakout potential of the original High School Musical. He had decided to check in on the production of a made-for-Disney-Channel movie being filmed in Salt Lake City, just one of a number that had been green-lighted. He loved everything about it—the actors, the writing, the music, the message—and called Sweeney to tell her he thought that it might be the next big Disney thing.

That was an understatement. Mostly through word of mouth, the tale of East High basketball-star Troy Bolton (Zac Efron)—who falls for brainiac Gabriella Montez (Vanessa Hudgens) and realizes his own performing ambitions when they are pushed into a fateful karaoke duet, overcomes his own fears and defies his basketball coach/dad to co-star with her in the school musical, and along the way leads the school’s various cliques to recognize that “we’re all in this together” and “we’re different in a good way”—became the biggest kid-hit of the decade. More than 255 million people have seen it worldwide.

If word of mouth provided the initial wind at HSM’s back, Ross lost no time in unleashing the Disney marketing machine to set it flying. It became the top TV movie in 16 different markets—from Chile to Norway to Taiwan. Its soundtrack was the best-selling album of 2006, and there was a best-selling junior novel as well. A High School Musical concert tour sold out in 42 dates in North America, and then went on to a five-country Latin American tour. Its DVD sales quintupled that market for Disney, which used to get about $15 million annually, but chalked up $72 million in 2006. Within a year, more than 2,000 schools had performed a version of High School Musical licensed by Disney. There was a High School Musical: The Ice Tourby the following September, and three global touring companies of the show, not to mention doll, DVD, poster, and other paraphernalia sales.

It’s fair to say that Walt would have been proud.

“Once Disney has something like this,” says Baine, the SNL Kagan analyst, “they can run with it farther and faster than anyone. In this case, it is hard sometimes to know that it was Ross who found the reason to do it, to know which property was worth doing it for.”

Ross says that he was merely reverting to an old Disney formula: find a really good show and then find likable stars to play in it. Having virtually ceded the younger group of children to his competitors, he had a smaller spread of ages to which to appeal. Still, he didn’t want to circumscribe that group too narrowly, so picking a high-school type play let him get both the kids already in high school and those who were old enough to have high school aspirations.

“We were not as successful in pre-school television, so then it meant targeting older kids,” he explains. “Our core was the older tween audience, say ages 10 to 14. So then you aim for a 14-year-old, but try to have an entry point for someone, say, six to eight, if possible.

“I just think that a seven-year-old can watch High School Musical, but it will be more understood by someone 11 or older. You just have to recognize what kinds of entertainment will do that,” he adds. “And you have to nurture people who can do it for you.”

In the case of High School Musical and, indeed, Hannah Montana, it is also using those people a second and third time around. With the core audience clamoring for more—but aging rather rapidly—and the actors not getting any younger, either, that means getting back on the project fast. High School Musical 2—the gang spends summer vacation putting on a show at a resort—came out within a year of the first (295 million viewers worldwide). High School Musical 3: Senior Year, which was produced for theatrical release first rather than TV, premiered 18 months after that.

The response provided no hint that the franchise is losing steam. Released last October, in the first downstroke of the recession, the film took in $42 million in its opening weekend—setting a new record for musicals and G-rated movies—and went on to earn $252 million worldwide in theaters. The soundtrack reportedly sold nearly 300,000 copies in its first week on sale in the U.S., and has notched 1.3 million sales in the U.S. and more than 2.3 million worldwide. More than 3 million DVDs have been sold. A fourth installment, with a new cast, tentatively titled High School Musical 4: East Meets West and introducing East High’s crosstown rivals, the West High Knights, is reportedly in the works to air in 2010.

Hannah Montana’s initial success as a series spun off a live concert-tour by Miley Cyrus—you may recall news reports about desperate parents offering thousands of dollars to scalpers or on eBay, or making up tragic stories to score contest tickets. It was soon turned into a movie, Hannah Montana/Miley Cyrus: Best of Both Worlds Concert Tour, released in February 2008, that grossed $71 million worldwide, despite appearing in fewer than 700 theaters. This past spring, Cyrus starred in a scripted Hannah Montana movie, which took the star back to her Tennessee roots, which brought in a reported $79 million in the U.S. and another $64 million internationally.

“It is not really genius but hard work and persistence that makes someone like Rich Ross make it at a place like Disney,” says Stacey Snider C’82, chief executive officer of the Hollywood studio DreamWorks. “He has learned over time what works with young talent and how to get it before young audiences. It isn’t just High School Musical, but a run of good programming in just the right places. There aren’t many like him.”

Back in February, Ross and Disney embarked on a new effort to work some of that magic on TV’s most elusive audience—boys—with a new cable channel and website, DisneyXD.

The general thought in Hollywood is that girls will watch Hannah Montana on TV, check out her outfits on the computer, listen to Miley Cyrus singing on the iPod and have an Entertainment Weekly story about her open in front of them, all at the same time. Boys, so the theory goes, are one-trick animals. If you don’t get them on the tube, then you’d better have a video game ready or they are off doing something else.

It’s not that boys don’t watch the Disney Channel—the audience is actually 40 percent male—but there’s no doubt that girls drive the focus of programming. Ross would like a High School Musical for boys, essentially, maybe something like a TV Pirates of the Caribbean, which went from a Disney theme park ride to a movie to a merchandising profit center. But he wants to avoid the fate of Fox in the 1990s, which started the Boyz Channel and its companion Girlz Channel, both of which failed and were castigated for intentionally segregating the sexes. Ross sees Disney XD as the more action-oriented, and perhaps gaming-oriented channel, which would appeal more to boys but not exclude girls. Its shows include Zeke and Luther, about a pair of would-be skateboarding stars; Aaron Stone, about a teenager who is recruited to be the real-life version of his favorite video-game hero; and the animated series Phineas and Ferb, which focuses on the antics of two brothers and their meddling older sister, and which also airs on the Disney Channel.

Besides serving the boys’ and girls’ entertainment needs, Ross wants to get, at least in a small way, adults to watch as well. “It was always that I believed there should be two lines of humor—at least in the movies—to attract adults,” says Ross. “What we have been able to deliver is that we have families in our shows and movies. High School Musical, whatever it has become, I thought it succeeded because it had a powerful story line. It was about a kid trying to live up to his father’s expectations, and then the story of a father trying to become proud of the kid who has taken his own path. We were able to deliver a father-son relationship with a message: that the best thing is to help your kid live out his own dream. That is what Disney tries to do—have it all in that way.”

Though he is approaching 50, Ross does not think he wants to leave children’s programming just as he seems to be perfecting it. He knows that by his own formula, he needs to keep shopping for the next Miley, the next Jonas Brothers.

“I like that our actors are the same age as their characters. Miley is a teenager, just like Hannah,” he says. “I hate it when someone 25 is playing some 17-year-old. The kids want to relate to someone really their age, someone who may be sometimes a celebrity, but also someone with their issues.”

There are practical reasons at work here. For example, it was rumored that Zac Efron was looking for $10 million to return as Troy Bolton in a fourth HSM movie. Also, as they age, teen stars may lose their status as role models, as the example of Lindsay Lohan, say, demonstrates. Both Efron’s co-star Vanessa Hudgens and Miley Cyrus have had public relations flaps over behavior that seemed to contradict their wholesome images—Hudgens over revealing pictures sent from her cellphone that wound up on the Internet and Cyrus over a photo spread in Vanity Fair that was deemed too suggestive—though neither controversy seemed to cause any lasting damage. But beyond those considerations, there is the question of believability and identification with the audience.

“The key is this: Can the teen viewer say, ‘I am just like…’” Ross says. “There are literally a record number of kids trying out for drama and theater in high school. I believe it is because they have seen High School Musical and said, ‘I am just like…’ To believe good entertainment can inspire that is why I am in this business.”

Ironically, Ross’s mom, who helped him get that first important internship at William Morris, was never a fan of his watching so much TV when he was young.

“But my Dad was. He never feared that I wouldn’t do my homework,” says Ross. “We formed a bond over TV. Pink Panther and Scooby-Doo, whatever it was.

“To this day, my dad watches our stuff, and that is the best confirmation of all,” he says. “It is wonderful when a teenager at heart can just relax with what you have worked so hard to do.”

Robert Strauss is a lecturer in the English Department and a writer in Philadelphia.

SIDEBAR

Living in Disney(Channel)World

We’re in the car and the question comes before I even turn on the ignition.

“Daddy, can we listen to something?”

Lately, the something has been Hannah Montana, recutting the grooves in my brain previously etched by High School Musical during the drive to and from my daughter Lily’s preschool. Many days I wake up with “Bop to the Top”—a Latin-flavored paean to showbiz competitiveness by HSM’s sister and brother act Sharpay and Ryan—or Hannah’s girl-power anthem “I Got Nerve” playing in my head.

Both CDs are actually vintage items in today’s whirlwind entertainment universe, inherited from Lily’s big sister Sarah, now 12, who got them in the first flush of hysteria over HSM and Hannah Montana, all of three or four years ago. By that time, she was a veteran Disney Channel fan. She watched all the shows—I could list them—but her great love was Lizzie McGuire. Hilary Duff played the title character, a generally normal teenager, as I recall, except for having a cartoon alter ego. Somewhere in the house we have several of her CDs, along with VHS tapes (tapes!) of the TV show and of the Lizzie McGuire Movie (which bears a weird resemblance to Hannah Montana’s regular girl/teen idol premise: On a school field trip to Rome, Lizzie is mistaken for an Italian pop star, who looks just like her!).

By the time High School Musical and Hannah Montana really got going as entertainment phenomena, Sarah was already beginning to drift away a bit, drawn by edgier, alluringly inappropriate fare like Ugly Betty, America’s Top Model, and The Bachelorette available on the grown-up channels. What that meant was that she still watched the Disney shows a gazillion times, but generally kept quiet about it, and beyond the music and DVDs, didn’t ask for much other stuff. Lily is making up for that, though.

Sarah, who sings and acts herself, was still very eager to see the third High School Musical movie, and she got Lily excited about it, too. We all went on its opening weekend last fall, doing our part to ensure the film’s record-breaking debut. And that’s when it began. After we got home, we dug out the original version DVD and watched it (and watched it, and watched it). Things snowballed from there.

In addition to the HSM 3 DVD, a partial list of merchandise purchased for Lily since then would include an HSM wall clock, lunchbox, pink zippered “hoodie,” sheets and pillowcases, bathrobe and pajamas, and a couple of different styles of HSM-branded underwear. She has Hannah Montanaunderwear, too.

When we were buying Lily supplies to go to kindergarten this fall, she split the difference, choosing a High School Musical backpack and a new Hannah Montana guitar-shaped lunchbox. And for her fifth birthday in July, her aunts and grandmother added Sharpay’s pink Mustang convertible and “Fabulous Fashion Closet,” an East High Wildcats cheerleader outfit, and a working microphone that lets you sing along with two songs from HSM 3. Sarah got Lily the soundtrack CD, which has given us something new to listen to in the car while we wait for High School Musical 4 to come out.

Judging by Rich Ross’s comments in the accompanying story, Lily may be a little young to graduate from Playhouse Disney to the Disney Channel. She still watches those younger shows—although, actually, she’s more of a PBS Kids fan—and I don’t know how much she gets of the stories. But she’s darned cute singing along to the songs. And truth be told, I’ve had worse things playing in my head when I wake up.—J.P.