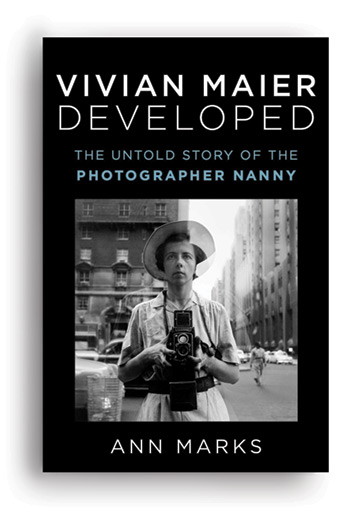

Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny

By Ann Marks W’80 WG’81

Atria Books, 2021, $40

A new biography probes the mysterious life of reclusive photographer Vivian Maier.

Ann Marks W’80 WG’81 loves movies. But her real passion is solving mysteries. In early 2014 her two obsessions met like a match head hitting a strike pad. The resulting collision ignited a seven-year odyssey that has illuminated the secret life of the late Vivian Maier, a nanny and recluse, who may rank among history’s greatest photographers.

It began when the former chief marketing officer of Dow Jones watched Finding Vivian Maier, an Oscar-nominated documentary directed by John Maloof and Charlie Siskel.

In 2007, two years before Maier’s death, Maloof paid $250 for some of the contents of her storage locker, which had been sold at a foreclosure auction. He came away with 200 boxes containing eight tons of materials. Newspapers accounted for the bulk of the trove, but the cartons also held 140,000 images—photos, negatives, and unprocessed rolls of film—that Maier created between 1950 and 1999 but had never showed to anyone.

“I couldn’t get it out of my head,” Marks recalls. “There were so many puzzles in Vivian’s life, and I couldn’t believe Maloof couldn’t untangle her mysteries.” The film was remarkable for more than Maier’s photography. “Everyone interviewed in the movie said contradictory things about her.”

That night she Googled Maier’s name. “I became a little obsessed. I got caught up with everything anybody had written or said about her,” Marks says. Soon she contacted Maloof to ask if she could help him investigate Maier’s background. Much was at stake. Maloof, who later bought most of the storage unit’s contents from others, had stumbled upon a treasure. But there was a catch. No one knew if Maier had an heir. Until that could be determined, a legal—and financial—cloud encumbered her estate.

Marks was baffled. Why hadn’t Maier ever showed her work? Why was next to nothing known about her family? Why hadn’t she become a professional photographer? What had made her a hoarder? Had she suffered from mental illness?

These questions became the catalyst for Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny, Marks’ first foray into biography, which was published this December by Altria Books.

To research the book, Marks looked at every last image in Maloof’s cartons, and sifted the other contents. She interviewed 30 people who knew Maier either as a child in France, as a young adult in New York, or from Chicago, where Maier spent the last 53 years of her life. She dove into physical and online archives, ranging from 1940s Manhattan phone books to turn-of-the-century marriage records.

“Vivian just kept revealing and revealing herself. I could have really gone on forever. I looked at every record. I reached into one of her coat pockets and found a two-page photo journal she made in January 1954 that was all crumpled up. I just kept going. I found all kinds of people who knew her—who had not been found before. That was all new, and now we can understand why she got into photography and her motivations,” says Marks. “There were some big revelations, and it ended up that a lot of conclusions people had made about Vivian were just wrong.”

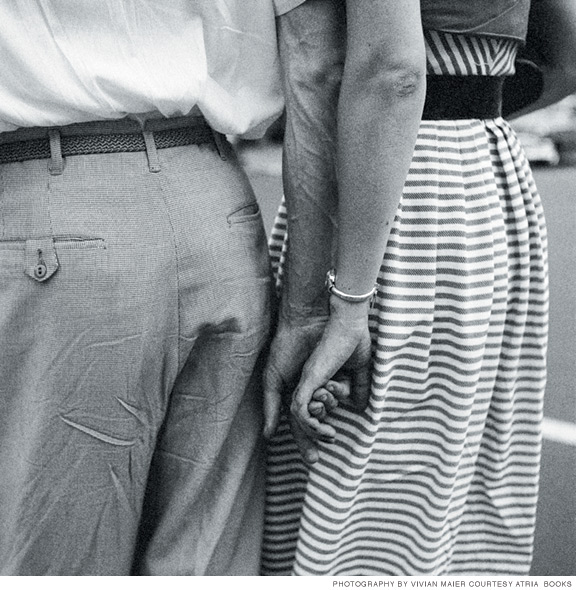

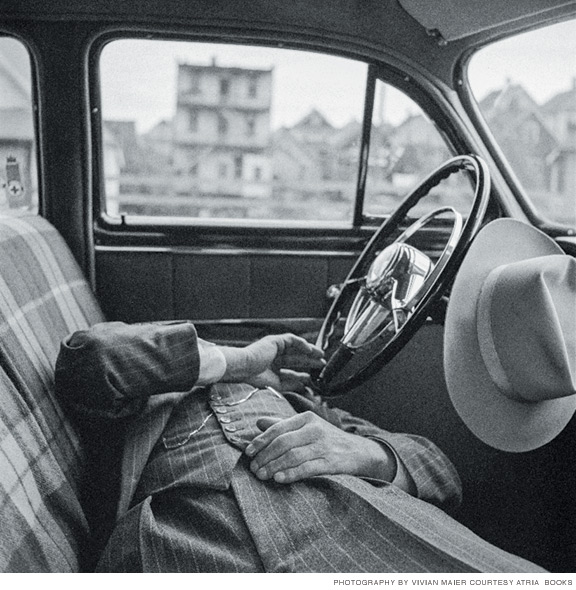

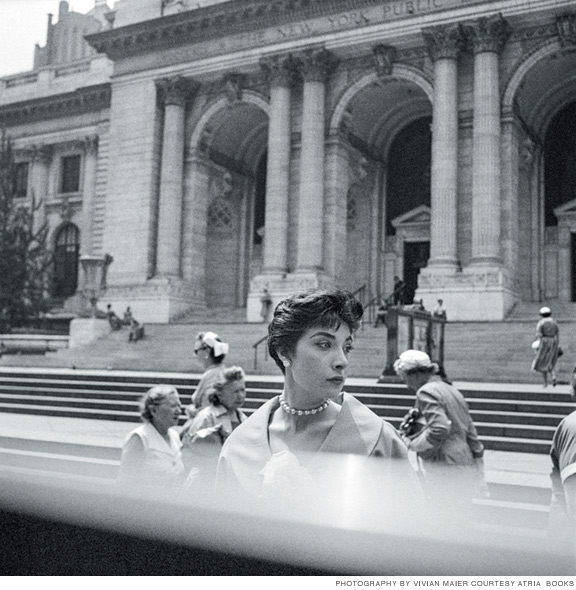

Zero. That’s the number of Maier’s photographs that were shown publicly when she was alive. From 1951 to 1996, Maier worked as a live-in caretaker for children (and infirm adults), first in the New York City area and then in Chicago. With a Rolleiflex, Leica, or Robot Star camera around her neck, Maier took her young charges on urban expeditions or made solo treks, often to seedy areas.

Nothing escaped her attention. She returned again and again to certain themes—geometric cityscapes, bums, movie stars, self-portraits (600 in all), hats, hands, snow puddles, shadows, solitary leaves, landscapes, clotheslines, mannequins, newspaper headlines, strip club marquees, mirrors, nuns, brides, cops, presidential candidates, trash cans, sleepers, American Indians, mixed-race families—recording images that sometimes revealed droll incongruities but more often exposed melancholy moments that revealed her profound compassion for the human condition.

Today, 13 years after her death at age 83, Maier is increasingly recognized as one of the finest photographers in history. Museums and galleries from Denmark to Des Moines, and Bulgaria to Brazil, have shown her work to record audiences. “As one the greatest masters of her medium, Vivian Maier finds herself in that exceedingly rare class of great 20th-century street photographers like Helen Levitt, Garry Winogrand, Joel Meyerowitz, and Lee Friedlander,” says Jim Ganz, the senior curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

She passed through the lives of her families the way Churchill described Russia—as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” Once, when neighborhood children were casting a play, they asked her what role she’d like. “I’m the mystery woman,” Maier replied.

The willowy nanny had a distinctive look. She wore floppy hats, oversized men’s coats, brown size-12 men’s shoes, and skirts paired with feminine Liberty of London blouses sporting Peter Pan collars. Often stone-faced, she referred to herself using the royal “we.” To a cousin who grew up with her, Maier seemed like “an extraterrestrial.”

Marks contacted her former charges, many of whom had strong memories. “She would see a subject, open her camera, focus it, and she’d snap it. It was just bam! It was fast. She went from walking to focus to shoot in under a second. The subject wouldn’t even have time to react,” recalls Inger Raymond, who said her nanny had odd reactions to men. “I would bet money she was brutalized in some way—attacked or molested.”

Marks describes herself as “analytical and very fact-based: I like to look at the facts of a situation and then determine people’s motivations.” That proved a productive way to approach the mysterious Maier, whose family and childhood were all but unknown. Marks, who oversaw market research and circulation for the Wall Street Journal and Barron’s during her corporate career, believed the key to unlocking Maier’s history—and solving the riddle of a possible heir—lay in learning about her utterly unknown brother Carl.

“I hypothesized that he had been incapacitated through either illness or incarceration … I spent months sifting through asylum, hospital, and inmate files on instinct alone,” Marks writes. “After peeling back layers of data” in New York’s state archives, she chanced upon a 1936 reference to a “Karl Maier” in a Coxsackie reformatory.

“There were hundreds of Karl, Carl, and Charles Maiers in the tri-state area—but when I was apprised of the inmate’s birthday, a chill traveled down my spine,” she recalls. When Marks visited the archives, a volunteer handed her a three-inch thick folder that held the story of the Maier family told from the perspectives of Carl, his parents, both grandmothers, and the reformatory.

“It was a biographer’s dream. It told the whole family story. It had words in their own handwriting, and their personalities came out. It was just unbelievable that it exists,” says Marks, who found no evidence Carl fathered a child.

Illegitimacy, bigamy, parental rejection, violence, alcohol, drugs, and mental illness ravaged Vivian Maier’s early years. She was a survivor. A year after her birth, her unstable mother separated from her father, a violent alcoholic. Carl, a drug addict, suffered from schizophrenia and lived for many years in an institution. Vivian’s parents and adult relatives treated her like “wallpaper,” according to Marks.

Marks spared no effort finding people who had known Maier as an adult. It took her a year to find her New York City neighbors, the Randazzos. Maier took 24 pictures of them in 1951—but the 1940 census showed 700 New York City families with that name.

After scrutinizing high-rises in backgrounds of rooftop photos of the Randazzos, Marks examined old photos of the city, searched Google Earth, and pored over OldNYC.com, which maps every Manhattan street with vintage photos. The website revealed a landmark in the image, a clue that led to others, including a 1930 census record of a Randazzo family on East 63rd Street, one block from Maier’s home.

After sifting through obituaries, Marks found 80-year-old Anna Randazzo Cronin in Queens. Cronin remembered Maier’s distaste for physical affection, the way she recoiled from hugs.

In a feat of investigatory magic, Marks located a child Maier nannied during the mid-1950s in Manhattan. Though she knew the family’s name—McMillan—and their approximate address—between 360 and 390 First Avenue—the trail went cold from there. For leads, Marks scrutinized photos of their apartment’s interior. She saw nothing.

Then she lasered in on a photo of a little girl with a toy telephone. When she enlarged the label in the center of its rotary dial, minuscule letters appeared: SARAH. Armed with the first name, Marks found a Sarah McMillan with homes in Manhattan and Hopewell Junction, New York.

Maier had taken photos of the family’s upstate Christmas tree expedition. Google Earth revealed a home near Sarah’s that matched one of the exposures. Sarah had passed away, but her sister Mary—whom Marks tracked down in New Mexico—said Maier refused to share her photos with her parents: an early sign, perhaps, of her hoarding disorder.

Marks’ research proved that as a young adult in New York, Maier had wanted to be a professional photographer. She shared her work with others and tried to sell it. “She had a mental illness, and she was hoarding photographs, and it became progressive as it always does,” says Marks. “The biggest revelation I found is we shouldn’t assume Vivian didn’t want to show her work. If she wanted to share her photographs, she couldn’t share them. She just couldn’t have let her photos go. It had nothing to do with her real desires.”

In Marks’ view, Maier’s illness kept her a camera’s distance from other human beings.

“Photography was everything to her. It was a way she could express herself the way other people express themselves through relationships,” says Marks. “If you can’t have your own experiences, photos allow you to possess those yourself.”

Maier lived a heroic life, according to Marks. “After all she went through, she never let herself be a victim. Most of the time she was really happy, upbeat, and cared about her children. She lived the life she wanted to live. She was proud of her work,” says Marks. “She knew she was good.”

—George Spencer