Artist Gwyneth Leech C’81 started drawing on used paper cups as a distraction when she got “antsy,” but “then it began to really take over.” A few hundred cups later, she spent six weeks doing the same thing while sitting in a window in New York’s Fashion District in an exhibit called Hypergraphia.

Q&A by Molly Petrilla

Photography by Marianne Barcellona

On a stormy Monday morning at the end of February, Gwyneth Leech C’81 bought a cup of Irish tea to-go (milk, no sugar) and headed to a display window in New York City’s Fashion District. She spent the next hour or two drawing swirling, plantlike patterns on that and other paper takeout cups—all of which had at one time housed her morning coffee or afternoon tea—as passersby gawked or whispered or smiled or knocked on the glass to say hello.

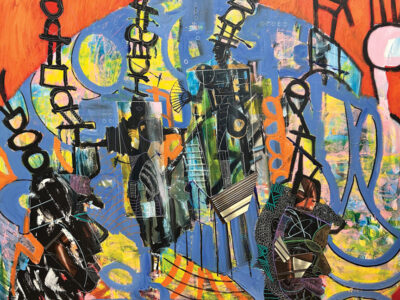

Then she came back the next day and did it all again, over and over until a full six weeks had passed. The doodles evolved, the drinks changed, but her canvas stayed the same: cups with a matte paper outside and waxy plastic inside. She started with about 250 pre-drawn cups strung up in the window around her and another 25 or so scattered at her feet. By the end of her window residency, she’d created another 100 cup drawings that joined the ones around her. She called the whole thing Hypergraphia, which means the overwhelming urge to write or draw.

“Partly, I wanted to see what 375 cups looks like,” she says, “but I also thought it was a nice-but-provocative way to bring people’s attention to our waste production; it made me think a lot about upcycling and recycling.”

An accomplished painter who has also worked with ceramics, video, and printmaking, Leech has exhibited her work around the world, including solo exhibitions in Edinburgh, Glasgow, London, Philadelphia, and New York City. In 2006, she began a series called Perfect Families, and since then has been painting portraits of alternative and mixed-race families she meets in New York City.

Inside her 13th-floor studio in the heart of the Fashion District, Leech shows me some of her favorite cups. They’re as diverse as you might imagine: cityscapes based on her soaring studio view; vines and other mesmerizing plantlike patterns; abstract shapes and designs of all sorts; a bright springtime landscape from her sister’s place in upstate New York. “For whatever reason, [the cups] are a useful form for me,” she says. “Shakespeare wrote sonnets. Bach wrote fugues. I draw on used paper coffee cups.”

What’s the story behind Hypergraphia? Had you been drawing on cups for a long time?

About three or four years ago, the places I go for various meetings all of a sudden switched from Styrofoam to paper cups. I tend to get very antsy [in meetings], and I have to draw. Instead of doodling in my notebook, I started doodling on these new matte paper cups. I began doing that very regularly, and eventually my artist friends said, ‘This is your artwork.’ So I started doing it in the studio as kind of a warm-up, and then it began to really take over. Last fall, I realized I had accumulated a significant body of cups, and I began to think about where and how I could show them.

Aside from the obvious cylindrical surface, what did cups offer you that’s different from, say, a traditional stretched canvas?

I like to work across a lot of forms and styles, and the cups suddenly gave me a consistent form and a way to do anything I pleased. I found when I was working on them, I gave myself full permission to do anything I wanted. They surprise me all the time because they’re so various. It really seems to be a bottomless well [of inspiration] for me. Anything that can help you generate so much imagery and tap into so many different kinds of ideas is a really useful form.

The work I’ve done on them is very unselfconscious. They’re like a 3-D sketchbook that you can stack, which is nice because I’m really attracted to sculpture and 3-D projects, but storage has always been a huge issue. The cups are great because I can pack all of them into a couple of IKEA bags.

New Yorkers have a reputation for always being in a hurry, almost to the point of having blinders on. Did people who passed by the window generally notice what you were doing and stop to watch you work?

I had this whole system of determining who was going to stop and who wasn’t. The smokers—they’re just looking for their doorway. The successful shoppers—ones who already have shopping bags—they’re happy, they’re probably going to stop and look. People on their way to lunch don’t look, but people on their way back to the office do.

The doorway for street sweepers was also right next door. They went in and out all day with their trashcans, and they used to linger outside and look at the installation evolving. We had a few conversations about what it all meant.

It must affect your work when people are watching or talking about it right in front of you.

I knew it wouldn’t be the kind of focused studio time that I have here, but it was an opportunity to see how people reacted to the work. That’s an unusual perspective that artists don’t often get. The work I did in the window was not self-conscious. It felt like a safe space—very quiet. People were out on the street, but there was an interesting feeling of distance and proximity at the same time.

So would you say there was a performance element to it?

Not really, because what I was doing was not self-conscious; it wasn’t studied. It was more like recreating a little piece of your studio so people can see your materials and your working process. I had a lot of my pens and inks and brushes from my studio, and an armchair from my home. I made myself very comfortable. If anything, it was a complete inversion of [performance artist] Marina Abramovic’s ascetic, disciplined, painful, endurance type of performance. I decided the artist would be comfortable, present, and not aloof.

On the whole, people were completely delighted [by what they saw]. Quite a few people came in through the door to ask me questions.

What did they want to know?

They were curious about the materials and how permanent the cups are. That’s another part of the project: I have a friend who’s an encaustic painter, and she helped me coat the cups in a bath of molten beeswax and damar resin to preserve the paper from moisture and oxygen and oils.

One of the remarks I heard a lot was, ‘Wow, that’s a lot of coffee. That’s really scary!’ I wanted to say, ‘It’s decaf! It’s decaf!’ I actually have a very low tolerance for caffeine. If I drank a giant-size coffee, my hands would shake so much that I wouldn’t even be able to draw.

Even if it wasn’t necessarily full-strength coffee, did these cups all come from hot drinks you’ve purchased?

Yes, and as part of this project, I gave myself full permission to go into any coffee bar that caught my eye around the city. I was looking for little start-up coffee bars—I tried to avoid places like Starbucks.

Occasionally, someone will offer me a cup and if I like it, I’ll take it and I might draw on it, but I always say, ‘I can’t take responsibility for your consumption! My own is bad enough!’ I have friends who say, ‘Just buy a travel mug. This is ridiculous.’ I’ve bought a few over the years, but I don’t like them for various reasons: they bump my nose, I don’t like the way they make the drink taste—that sort of thing.

Did you see a change or evolution in what you were creating over those six weeks in the window?

Before I went into the window, I’d been working on a series of paintings based on aerial views of New Jersey salt marshes. My head was really in that above-the-earth perspective, and a lot of the cups I’d been doing in the studio were more abstract. Once I was in the window, I got very into looking at the people walking by. What I was drawing started to get a lot more figurative. There was a definite shift that had to do with location and energy. Sometimes, the conversations I had there would also spark a cup image. One day, we were talking about pets and dogs, and suddenly a lot of dogs emerged on a cup.

What about its effect on you as an artist?

It’s all grist for the mill. For me, a project that had so much sociability built into it was extremely enjoyable. Artists generally work alone in the studio, but I do crave interaction and community. Over the last year in particular, I’ve done quite a few projects that involve being in public and working with people. The conversations I had while I was drawing seemed to be a big part of the window installation. I don’t know where I’ll go next with it; I might retreat for a while and just go back to the studio to regroup.

Molly Petrilla C’06 is a frequent contributor to the Gazette and writes the magazine’s arts blog.