Reflections on 70 years of avant-garde composition.

Composer George Crumb Hon’09 is sitting front row center while a professional pianist taps inside her Steinway with a xylophone mallet, rubs its strings with a drinking glass, and uses her fingers to pluck it like a harp. She moans and shouts and caws like a crow. She even pops on a red clown nose for a movement entitled “Clowns at Night.”

Margaret Leng Tan is performing “Metamorphoses (Book I),” one of Crumb’s newest works, as part of Zeitgeist: George Crumb at 90—a three-night concert festival at the Annenberg Center, dedicated to the Penn professor emeritus of the humanities who turned 90 on October 24.

Before Tan, who is famous both for interpreting avant-garde works and as “the queen of the toy piano,” took the stage that night, another pianist performed a much earlier piece Crumb wrote for solo piano: “Makrokosmos (Book I)” from 1972. Like Tan, he knocked and reached and plucked. Like Tan, he pressed his forearms across the keys. He moaned. He occasionally howled out words.

An active composer since he was a child, Crumb rose to prominence in the 1960s and 70s, winning both a Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1968 for “Echoes of Time and the River” and a Grammy in 2001 for “Star-Child,” which he composed in 1977. Musicians all over the world have tackled his work, and in 2003, David Bowie listed Crumb’s “Black Angels”(1972) as a life-changing listen.

“George is a composer of historic importance,” says James Primosch G’80, a music professor at Penn who co-curated the concert festival and also performed in it. “He represents a shift in American music, which at one time emphasized structure and intellectualism. George was part of a movement of composers that emphasized more expression and feeling—not without structure, but trying to strike a different balance.”

Primosch notes that experimentalists embrace Crumb for his unorthodox performance techniques, but he says traditionalists admire him, too, “because his music really is rooted in earlier music.”

“Along with his Penn colleagues George Rochberg G’49 and Richard Wernick,” Primosch says, “George helped open up a wider range of what seemed possible. His work gave people permission to explore possibilities that they might not have felt they could explore otherwise.”

The festival presented a dozen of Crumb’s works, ranging from pieces that he wrote at 18 years old to a 1998 series for guitar and percussion inspired by his family dogs. The final night concluded with “Black Angels,” which Crumb wrote for electric string quartet as a direct response to the Vietnam War. It opens with piercing shrieks from the instruments, which sound like a swarm of demented insects, and continues to surprise with gongs and vocals and pops and buzzes throughout its 13 movements.

“George’s music is about casting a spell,” Primosch says. “It’s ritualistic and otherworldly. There’s nothing mundane.”

Shortly after the festival celebrating 70-plus years of his compositions, Crumb spoke with Gazette contributor Molly Petrilla C’06 about his journey into composing, his mission to draw new sounds out of traditional Western instruments, and the 30 years he spent teaching at Penn. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

When you spoke with Jim [Primosch] on stage at the Annenberg festival, you mentioned that your brother was a virtuoso whistler. I’ve also read that your father was a clarinetist with the Charleston Symphony. Was everyone in your family musical?

Yes. My mother was a cellist. My brother, in addition to being quite an astounding whistler, also played the flute. We always had a lot of chamber music going on—arrangements of various pieces for the four of us.

We didn’t have much of a record collection because recordings were relatively expensive in those days, but my dad had a collection of scores. That got me into wanting to know how music was made, how it looked on the page, how composers had arrived at the effects they achieved. But I didn’t have any formal instruction in composition until I went to the University of Illinois and then later the University of Michigan.

Do you remember how old you were when you first started composing?

I think I was around 10 years old, which is very late compared with a lot of traditional composers—I’m talking about Mozart and people of that ilk.

What were your earliest pieces like?

They were little pieces for piano or clarinet and piano—instruments that I knew. I wrote a piece for orchestra when I was about 16 years old that was played by the local Charleston Symphony Orchestra, but there was no originality there whatsoever. I was imitating other composers. I was very much influenced by Chopin and Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms. I was reinventing music that had already been composed. I didn’t find my own way until later.

How did you get to that point?

I think it was when I went to the universities I mentioned. Those places had actual teachers of composition. I learned a lot about composers like Stravinsky and Bartók and Copland, but I didn’t write my most original music until I was just about 30 years old, I suppose. It’s a long time to wait, but I was a slow developer as far as my own language was concerned.

Is there a piece that you feel underscores that moment of coming into your own as a composer?

There are a couple. The first is a transitional piece, “Variazioni” [1959]. It was several more years before I really got my music down to more my own style. I think the first piece of that development was “Five Pieces for Piano” [1962], which I wrote when I was teaching at the University of Colorado.

You came to Penn a few years later, in 1965, and taught music composition and theory here until you retired in 1997. Why did you want to teach, and how did teaching at Penn affect your own work?

It’s partly an economic matter. In the early years, when you’re first finding yourself, you don’t make an awful lot of money from composition for this kind of music. I was offered jobs both at the University of Pennsylvania and Swarthmore. I chose the University of Pennsylvania because there were doctoral students I could work with.

Penn was a really exciting school for me. Most of my teaching was private sessions with composition students, and there were a lot of very excellent students in composition—there still are. Now and then I ran a special class concentrating on the music of certain composers that interested me very much. Several times I gave classes on Gustav Mahler, who is one of my favorite composers, and was and is an important influence on my music.

Occasionally a student I’ve had gives me an idea for something of my own. That’s one of the nicest things about teaching. We also had a teacher who brought in musicians from India. Some of the students were interested in taking up the sitar or the Indian drums and he would give classes in Indian music. His room was right across the hall from mine in the music department, and these sounds would come floating across to me. That was a very strong influence.

Can you talk about this idea you came to—which we saw in “Makrokosmos” and “Metamorphoses” at the concert festival—of turning a piano into more than the instrument we usually see and hear it as?

That developed gradually. There were earlier experiments in that direction: John Cage had developed what he called the prepared piano, where he would put pieces of metal or something against the strings. But still, his pieces involved playing on the keyboard. I was more interested in keeping the keyboard intact but expanding it to include all kinds of extra notes that could be produced inside the piano—like harp techniques plucking the strings, like percussive techniques striking the strings with percussion mallets. All of those things became part of my way of using the piano.

Then that carried over to other instruments. In “Black Angels,” I was interested in expanding the sound possibilities of our conventional Western instruments. I think it came partly from my early interest in the music of other cultures. They had different instruments in some cases and the music sometimes had different techniques. Sometimes I even ask the pianist to produce vocal effects or hum along or sing a little, which you won’t find in a Beethoven piano sonata, of course. But I’m sure Beethoven never heard any music from India, for example. It was kind of a revolution in our own time: Composers suddenly became interested in different ways of producing sound and expanding the range of sound.

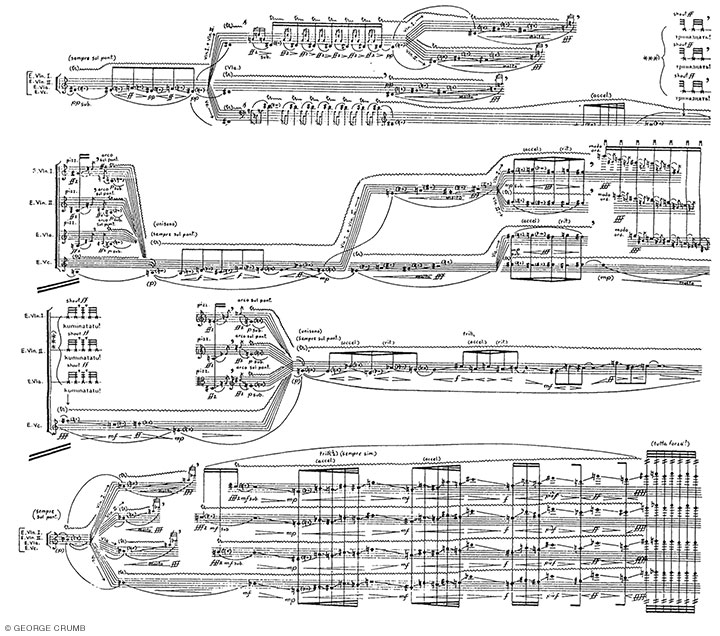

You’re also known for your hand-drawn scores—both the beauty of your calligraphy and the unusual shapes you form the staffs into: peace signs, swirls, crucifixes. And you’ve written entire pieces based on modern artworks. Do you have any training in visual art?

No, I don’t. I always loved to see music in a visual way, though. I always had the idea that music that sounds really exciting also looks exciting on the page.

How much of what performers do is written into your music, and how much is open to interpretation? This is a small example, but one that I’m stuck on from the concert festival: did you write in the music to put on a clown nose during “Clowns at Night”?

No, no. That was her own idea. But [my music is] pretty exact. I always describe in footnotes how a technique is to be executed. I think I was the first to use a drinking glass [to rub the strings]. It’s a way of bending the sound of a string or a group of strings. A lot of my scores are just loaded with footnotes to explain techniques or what’s involved in producing the sound that I want. A lot of young pianists don’t realize that you have to work at it pretty hard to master those techniques. You don’t just read the music and play the keys. It goes way beyond that.

You mentioned at the concert that you still read Beethoven scores every day to try to figure out how he did what he did. Which other composers have been some of your biggest influences and inspirations over the years?

Almost all the music of the past. Anytime I hear Beethoven or Schubert or Mozart—these are the greatest composers there ever were. Of course you can’t just imitate them, but I do quote them sometimes. I’ve quoted passages from Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” sonata. I’ve used a quote from Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, remembering my father playing the clarinet in our house. It’s usually not more than a couple of bars.

I think a lot of the very old music can still have an immense influence on our thinking, even though what we do won’t sound like old music. Some things change, but certain structural principles or musical gestures or even motifs can be an influence. I’ve learned so much from Debussy and Mahler, who haven’t been around for more than a century.

Looking back, is there a moment or an accolade that you feel represents the highest high of your career so far?

The most exciting performances were two works that dumbfounded me because of the incredible reception they had on the very premiere. One was “Ancient Voices of Children” [1970], which premiered in Washington, DC. That was recorded right away and went around the world. It spread my music more than anything else, together with one other work from that same year: “Black Angels.” There was an incredible reception to that piece, too. I never wrote a piece quite like that. It was breaking boundaries in every bar, practically, both in the way the sound was produced and in the musical ideas themselves. That was a breakthrough year for me. I suppose my career since then has been following up on the general stylistic direction and territory I discovered for myself in that year.

What do you know about composing now, at age 90, that you wish you could go back and tell yourself at 20 or 30 years old?

The main thing is to make it into an individual style of your own, even if there’s a strong influence. I don’t think any composer wants to be known as somebody who used another composer’s music but didn’t do it as well as the other composer did. You can be influenced, but you have to find your own way.

Can you talk about what you’re working on right now?

I just finished a work, so usually I need a little time to set myself up for the next project. But I hope I still have some ideas left in me. At age 90, you’re not quite as imaginative as you might be at an earlier age, but I’d still like to do some things. I don’t like the idea of retiring from composition. Some composers kind of fade away in their production at a certain age. They feel like they’ve done everything they have to do. I don’t feel that quite yet. Maybe I will next year, but so far, I don’t.