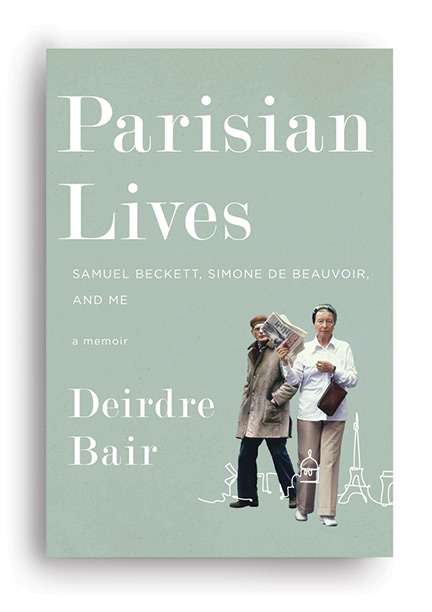

Simone de Beauvoir, and Me

By Deirdre Bair CW ’57

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 368 pages, $28.95

Deirdre Bair explores the tortuous process that produced biographies of two literary giants.

By Julia M. Klein

If you were ever tempted to write a biography, Deirdre Bair CW ’57’s revealing look behind the curtain would surely give you pause. Broken appointments, shifting memories, academic backbiting, freeloading sources, financial exigencies, and the vagaries of the publishing world were just a few of the hurdles Bair confronted while trying to pin down the two towering literary figures portrayed in her first biographies.

Published in 1978, Samuel Beckett: A Biography won Bair a National Book Award. She followed up—12 years later—with Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. These magisterial volumes launched a distinguished career that would encompass biographies of Carl Jung, Anaïs Nin, Saul Steinberg, and, most recently, Al Capone.

Now, aided by both the perspective of time and voluminous contemporaneous records, Bair is offering reflections on the nuts-and-bolts challenges of her initial biographical forays. In Parisian Lives: Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir, and Me, Bair, a onetime journalist and later a comparative literature professor at Penn, accomplishes several goals. Taking us into the cafés of Paris, the bars of Dublin, and Beauvoir’s comically cluttered living room, she gives us an unvarnished look at her sources. Detailing her errors and missteps, she shows how she found her vocation. And she leads us through her gradual feminist awakening in the face of the persistent sexism and condescension that dogged her, and other accomplished women, during the 1970s dawn of the women’s movement. The result is a detail-oriented, bracingly candid “bio-memoir.”

Bair’s projects were complicated, if also enriched, by the fact that both her subjects were alive and in a position to help or hinder her. Beckett promised to do neither, and she insists that he always kept his word. But she also suggests that the Anglo-Irish novelist and playwright was both a help and a hindrance. His receptivity encouraged his family and friends to cooperate. And his periodic rages—which subsided as unpredictably as they flared—were impediments, arousing anxiety about future interviews and copyright permissions.

As Bair recounts, her relationship with Beckett started inauspiciously, when he failed to keep their first Paris appointment and left her no word about why. This was, of course, in the days before cell phones and email, when someone who went missing could be all but impossible to track down. As it turned out, Beckett had become ill and fled to Tunisia to recuperate. But he did return, “bundled against the weather in a sheepskin jacket and heavy white Irish-knit sweater with a high turtleneck collar,” before Bair’s visit ended. “So you are the one who is going to reveal me for the charlatan that I am,” he memorably declared. And so a collaboration (of sorts) began.

Bair’s interactions with the Nobel laureate, who had been the subject of her Columbia University doctoral dissertation, were at once formal and constrained. Their numerous conversations weren’t explicitly off the record, but he nevertheless refused to allow her to tape-record or take notes (“No pencils! No paper!” he told her. “We are two friends talking.”)—terms that an experienced biographer might have more vigorously contested. Instead, the seemingly inexhaustible Bair would rush off after each meeting and try to reproduce everything they had discussed.

Beckett’s friends, for all the juiciness of their recollections, could be particularly infuriating. On one occasion, the Irish poet John Montague brought his wife and toddler, uninvited, to Bair’s Connecticut home. Commuting to New York, he demanded daily transportation to and from the train station and proposed to stay for several weeks. When Bair finally gathered the courage to evict the interlopers, they left behind a huge mess and an equally sizable transatlantic phone bill—and then told friends that Bair had tried to seduce the poet.

Bair’s first meeting with Beauvoir had an anxiety-producing prologue as well: the French writer known for her 1949 feminist treatise The Second Sex and her lifelong relationship with the existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre had given her an old, inoperative phone number. To reach her, Bair had to hand-deliver a letter to a Parisian neighbor of hers. When they finally connected, Bair’s impression was of a “very tiny woman” with brilliant blue eyes, wearing a turban and “a shabby old red bathrobe over a nightdress.” Beauvoir’s skin had a distinctive yellow cast, betokening cirrhosis of the liver.

Beauvoir announced that she would tell Bair “all the things you need to know,” suggesting that she would control the biography’s content. But, when Bair stood up to her, she backed off. This time the biographer was able to tape, as well as take prodigious notes, and their interviews, conducted in a mix of French and English, veered toward friendship. Bair sought to maintain her objectivity by declining to accompany Beauvoir to various parties and dinners, relaxing her wariness only if the event seemed helpful for the book.

By her own admission, Bair was wildly naïve about the art of biography at the outset. But she brought to the pursuit a background as both a journalist and a scholar. The seed of her first biography was her belief that literary criticism had neglected the importance of Beckett’s Irish heritage. Among her discoveries, from a cache of letters, was the tortured nature of his relationship with his mother, which precipitated his flight to Paris. In Beauvoir’s case, Bair was inspired by the (possibly faulty) notion that this was one woman who had somehow managed to have it all: a great love and a fulfilling career. Bair would end up noting the pain Beauvoir experienced in reaction to Sartre’s compulsive entanglements with young women.

Married herself, with two children, Bair dutifully juggled family responsibilities, filling the freezer with food before departing for Paris or elsewhere. (She describes her husband, a museum administrator, as mostly supportive; their marriage ended in divorce after more than four decades, an event not covered in Parisian Lives.) Bair also felt a responsibility to earn money to finance her reporting trips and contribute to family expenses. For a while, she alternated between low-level, short-term academic posts and reliance on grants and fellowships. Ultimately, she was hired to a tenure-track position at Penn, becoming an associate professor in the English department. Disgruntled by academic politics, she eventually left to pursue a full-time writing career.

The Beckett biography excited attacks from presumably envious male scholars whom Bair disdainfully dubs “the Becketteers.” Most shockingly, she was met by the repeated insinuation that she must have slept with Beckett in order to have garnered his cooperation. That was not the only sexist hurdle she encountered. “I spent many exhausting evenings,” she writes, “trying to move out of the reach of one after another drunken Irish poet, actor, playwright, journalist, or professor.” She says she grew accustomed to repelling sexual advances from sources, managing to convert many of them into friends. As she gained self-assurance, she also finally fired her astonishingly unhelpful literary agent, Carl Brandt, and found another, Elaine Markson, more firmly in her corner.

Parisian Lives makes clear how meticulous Bair was, pursuing hundreds of interviews and cross-checking every story with three or more sources before including it. Even as her skills improved and she grew more adept at discerning manipulations and untruths, her indefatigability seems never to have waned. Her memoir is disarmingly frank about all the difficulties involved in biography. But it also turns out to be a wonderful primer for anyone determined to pursue that art.

Julia Klein writes frequently for the Gazette.