Thomas Jefferson thought every generation should change the nation’s fundamental law. A new book imagines how that might have played out.

“The earth belongs … to the living, the dead have neither powers nor rights over it.” So proclaimed Thomas Jefferson, who believed that each generation of Americans ought to write its own constitution. The United States has instead, by and large, followed the counsel of James Madison, who argued that the nation’s longevity would be best secured by limiting opportunities to change its founding document. Yet the Jeffersonian impulse has echoed down the decades, firing the imaginations of citizens frustrated by the perceived limitations of a code designed to respond to the world as it was in 1787.

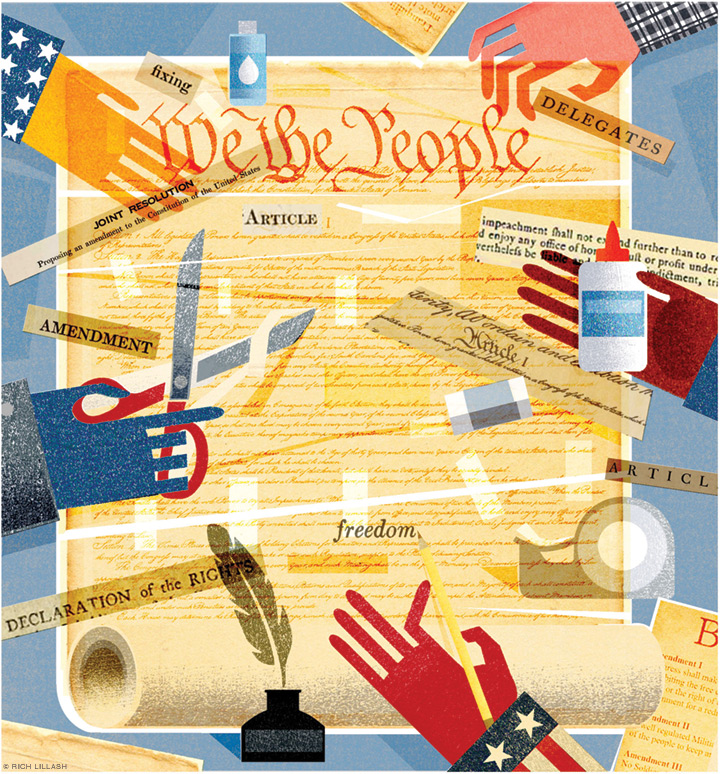

In A Constitution for the Living: Imagining How Five Generations of Americans Would Rewrite the Nation’s Fundamental Law (Stanford University Press, 2021), Beau Breslin G’93 Gr’96 mines America’s rich history of policy debate and disagreement to speculate about how things might have turned out if Jefferson’s view had prevailed. Would a Constitutional Convention of 1825 have wrought radical changes to the original template? What about 1863, or 1953? Breslin, a professor of political science at Skidmore College, uses this conceit to shed an unusual light on some of the country’s most momentous turning points—as well as some points of contention that have faded in our collective historical memory. Along the way, he offers readers fresh reasons to revere the 1787 Constitution, question the sacrosanct status it has acquired, learn from the experimentalism that has marked individual state constitutions, and ask the question: How much does any constitution really matter, anyway?

Breslin spoke with Gazette senior editor Trey Popp in October. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

If Americans had indeed rewritten the Constitution roughly every other generation, which iteration do you think would have changed the nation’s evolution the most, and why?

I think 1863 would have been a dramatic change to the Constitution. It might have fundamentally changed the direction of the country—because there’s no guarantee that Lincoln wins the election if the Constitution changes in 1863. That said, I’d say right now, 2022, would get the most radical change in the Constitution. You see reform proposals for constitutional change now that have never been embraced or thought about prior to this time.

What kind of reform proposals are you thinking about?

Eliminating the Electoral College. Doing things to reform the undemocratic Senate. And there are ideas like having a single eight-year term for the president, or a single six-year term that includes a confirmation election that would allow the president to stay on for an additional two years. If we had a convention today, there’s no chance that there wouldn’t be some kind of constitutional right to environmental protection. And what about mandatory income for all—that’s a reform being discussed. That type of change would never have come up before the 21st century.

You’ve listed things that might reasonably be considered to belong on a liberal wish list. Are there ideas you notice percolating on the right that might make for a lively 2022 Constitutional Convention?

Yes and no. Conservatives generally think, more so than liberals, that the Constitution is pretty solid as is. But there might be room for reserving greater power for the states. There would be moves toward balanced budget clauses in the Constitution from the right. I could imagine, on the far-right, a move toward protecting an unborn fetus, in the Constitution, as a person. So there are rights that the right would advocate for. But if you survey Americans, those on the right are pretty comfortable with our current Constitution and those on the left are a little frustrated with it.

Yet I also think that in a convention, there’s a bias toward the status quo—get enough people in a room, and you’ll see less change to the Constitution than those on the left would like.

You write that the Constitution has to accept some of the blame for the current state of American politics, and for America’s tribal mentality. How is the Constitution to blame?

One of the ways in which the Constitution has fostered our current state of tribalism is because of its brevity. It’s only about 4,500 words. That’s one of its great virtues, but because it’s so brief—especially Article II—you have the prospect of a demagogue-type president coming up out of nowhere. There are very few guardrails when it comes to Article II and the president’s power. And that was by design. The original framers in 1787 recognized that George Washington would set the precedent for the way in which someone doesn’t become a monarch or a demagogue. And Washington did that well. But by not having, for example, limitations on the expressed powers of the presidency, you have the possibility of an imperial presidency. The reality is that the presidency is the most powerful of the branches, and the least constrained.

Do you think changing those elements of the Constitution would be worthwhile, or could it introduce another set of problems?

This is where it gets tricky. On the one hand, yes, one’s first instinct is to say: we need to expand Article II to limit the power of the presidency in certain areas. But having broad authority, especially in the international sphere, has served us pretty well for last 245 years. Now some people might disagree because we’ve been the international policeman. But ultimately, we are an economically stable, safe, protected country—part of which is due to the fact that we are surrounded by oceans, but partly because we give flexibility to the executive branch to work through challenges on the international front. So creating those guardrails could have unintended consequences.

You spend a fair amount of time writing about state constitutions in this book. Why?

There’s been incredible experimentation in constitution-making at the state level. We’ve kind of put the brakes on that but before 1960, states were revising their constitutions on a regular basis. And there was really interesting experimentation. Not just obvious things, like Nebraska’s unicameral legislature. But expressions of rights and liberties that I think would help a 2022 Constitutional Convention.

A curious feature of this book is that even as you imagine successive revisions to the Constitution, broader historical developments continue to unfurl much as they did in actuality. So even though your 1863 Constitution tries to address regional factionalism and civil rights, you have the Convention of 1903 wrestling with the Black Codes and Plessy v. Ferguson. Did you frame each chapter this way purely to situate readers within a recognizable context? Or is there a deeper point here: do you think that the impact of any constitution is ultimately pretty modest—that constitutions essentially react to historical forces more than they shape them?

Both. From a practical perspective, anytime you do speculative history, you run the risk that what you imagine is just not credible. And imagining the effect of constitutions on historical moments was something beyond my capacity. But I do think we overinflate the importance of constitutions. Constitutions matter. They make a difference. But most Americans don’t even know what’s in ours—so I think assuming it has a day-to-day impact on American society is probably a little exaggerated.

Historically, I’m not sure we’d be in any different of a spot in 2021 if we lived in a Jeffersonian world. Because I’m not sure we’d have made radical changes. We probably would have relied heavily on the 1787 Constitution as our guidepost for every successive constitution. So I doubt we’d have a parliamentary system, or a unicameral legislature, or a dramatically different selection process for federal court judges. I’m not sure in 2021 our polity would look dramatically different than it does now.

That begs the question: Why have a constitution at all? Great Britain doesn’t have one, and they’ve managed OK.

I’ve spent my career writing about two questions: What are constitutions? And do they matter? The 1787 Constitution changed the world fundamentally for the better. Was it flawed? Yes. But I have deep reverence for the way in which it changed the world. It’s the most enduring national written constitution in history. And all but three countries—the UK, Israel, and New Zealand—have written constitutions. A big majority of countries in the world have bought into the idea of a written constitution as a difference-maker. And our constitution is the model for that. I think the only reason why the UK and New Zealand work the way they work is because of a longstanding tradition, but I would never suggest to any new country that they don’t start with a written constitution. Because it makes a difference.