The CNN correspondent whose head fills most of the TV screen may have nothing new to report from Iraq, but there is real news on another topic in the text crawling beneath him. The viewer is thus forced to read words and images at the same time.

The news media is one realm where word and image interact in interesting ways, but it’s important to note that their relationship has been debated since antiquity, says Dr. Catriona MacLeod, associate professor of German.

Continuing that tradition, word and image will be examined from a variety of angles during the 2005-2006 Penn Humanities Forum, for which MacLeod serves as co-topic director with Dr. Liliane Weissberg, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor in the Arts and Sciences and professor of German and comparative literature.

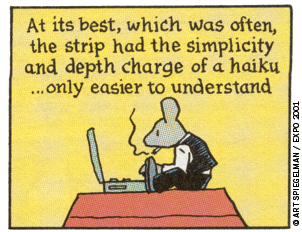

Kicking off the forum will be a public talk on September 27 by Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novelist Art Spiegelman. (The talk comes at the end of a conference for the International Association of Word and Image Studies, organized by MacLeod.)

Spiegelman’s best-known work, Maus, portrays the Holocaust in comic-book form, using cats to represent the Nazis and mice to represent their victims. “For a lot of people it’s an audacious thing to do—to talk about the Holocaust in a form that you might associate with a children’s or humorous popular genre,” MacLeod says. “In fact it raises dark questions about the Holocaust.”

Over the coming academic year, scholars will examine the tattoo, the X-ray, and the Sumerian tablet; the use of photography in novels; Medieval musical notation; and visual evidence in the courtroom.

“We have quite a rich program,” Weissberg says. “It’s an ideal topic to bring together the humanities faculty and move beyond the humanities.”

The topic has plenty of history, with word and image shifting in primacy. “In the Renaissance there was the notion of paragone, a competition between words and images,” MacLeod says. “Quite often in today’s culture we feel we’re saturated with images. Yet there have been other times when the image has been incredibly suspect. You only have to look to periods like the Reformation and the long history of iconoclasm. One good example of that is the smashing of the Buddhas by the Taliban government in Afghanistan a few years ago.” During the Romantic period, words and images came together in various art forms.

Today, she says, “there are many moments in popular culture and the high arts where you find the juxtaposition of word and image intended to be provocative and challenging.”

The word-and-image topic “seems to have struck a chord,” judging by the unusually large number of applicants for fellowships sponsored by the humanities forum this year, Weissberg notes. Perhaps “this is a time when people are particularly eager to rethink it—maybe because of digitalization, maybe because of the question of the future of the book, maybe because of the question of where the modern art world will go from here, and maybe because of politics and the restriction of making images in a certain way in certain religions.” The word-image relationship “touches people very much as we think about what is happening now in the world.”

—S.F.