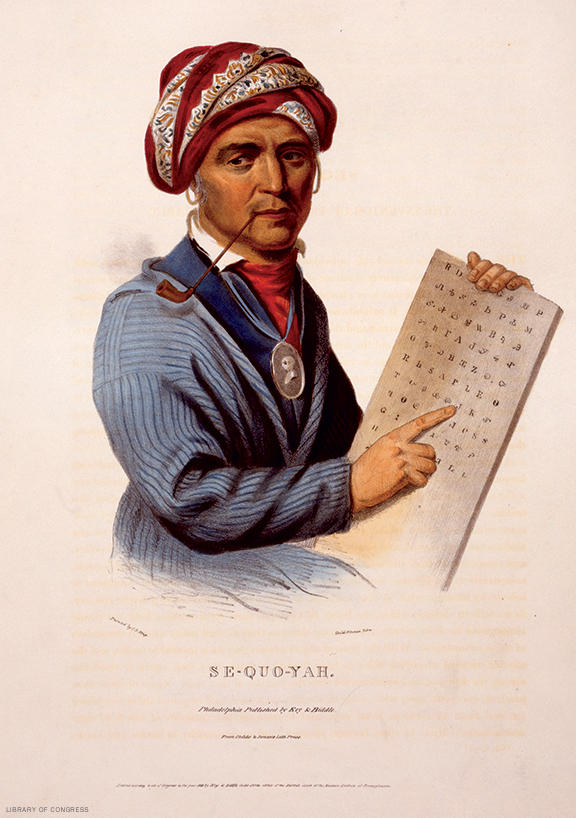

Sequoyah, inventor of the Cherokee alphabet.

Gathering at Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society in October, panelists ritually thanked the Lenni Lenape—in a dazzling variety of Native American tongues—for sharing their ancestral lands. At this groundbreaking conference, “Translating Across Time and Space,” respect was the dominant tone. But at least one speaker sounded a cautionary note, grounded in the difficult history of colonial conquest and language suppression.

“Our languages are alive,” declared Elder Bruce Starlight, a Tsuut’ina Nation language teacher. Addressing about 80 scholars, archivists, and others, he stressed the need for academics to involve community members in their language-related projects: “We are the experts—not you guys. And, so, the knowledge keepers need to be equally recognized. Without us, you’ve got no study.”

The conference focused on strategies for revitalizing endangered Native American languages, as well as bridging the gaps in power and perspective between Native Americans and academic experts. Talks explored topics such as digital tools for language instruction, the relationship between language and landscape, and collaborations among archives, universities, public schools, and Native American communities.

Organized by the APS’s Center for Native American and Indigenous Research, it was co-sponsored by the Penn Humanities Forum, whose topic this year is “Translation.” Patrick Spero G’04 Gr’09, the APS librarian, says the impromptu collaboration was a happy coincidence.

Bethany Wiggin, topic director of this year’s humanities forum, says she learned of the impending conference through the McNeil Center for Early American Studies and asked to join forces. One of her contributions was suggesting the keynoter, Winona LaDuke, a prominent Native American activist and writer.

Addressing conferees, students, and others at the Penn Museum, LaDuke spoke via Skype from the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in North Dakota, where she was participating in protests against the planned Dakota Access Pipeline. LaDukesaid that she often asked herself, “What would Sitting Bull do?” She argued that the pipeline posed a danger to both Native American sacred sites and the environment. “Indigenous people have been treated very poorly for the past 50 years in this state,” she said, “and that is still continuing to be true …. This is a moment of reckoning.”

Wiggin says that LaDuke’s address, while not explicitly about translation, reflected the notion that environmental justice and health are “part of thinking about cultural renewal and revitalization.”

The Native American languages conference was an early highlight of the 2016-17 Penn Humanities Forum on Translation, a cornucopia of public events.

Wiggin, associate professor and graduate chair in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and director of the Penn Program in the Environmental Humanities, has written two books on translation. So the topic was a natural fit for her.

“For a long time,” she says, “translation was viewed as being derivative, lacking creativity, sort of mechanical.” The forum, she says, attempts to demonstrate that translation “actually involves pretty profound creative processes” in its own right. Wiggin says she defined translation broadly, seeking out scholars whose work has used translation as a metaphor.

Among upcoming forum events is a four-film series, “Translation Trouble,” in collaboration with the Cinema Studies program and International House Philadelphia. The 1978 documentary Koko: A Talking Gorilla, screening February 15, questions the ethics of teaching human sign language to apes. Windtalkers, on March 1, is a 2002 World War II epic, directed by John Woo, on the role of Navajo Indians as “code talkers” for the US military.

At the Native American languages gathering, community leaders, scholars, and archivists—categories that frequently overlapped—discussed everything from the colonial past to the more hopeful present. For the most part, they embraced the idea that, instead of servingmainly as a repository for dead languages, “archives can promote cultural and linguistic renewal,” as Wiggin put it, by making their materials available to communities.

But Justin D. Spence, an assistant professor of Native American Studies at the University of California-Davis, says that access to archives has been hampered by geographical, financial, and other constraints.

“That’s something we’re trying to correct through modern technologies and techniques,” said Spero. The APS “hosts images for viewing on the web,” he added, and also shares its digitized collections in other ways.

Another takeaway from the conference was a startling finding about the relationship between language use and the health of Native American communities. In a paper on indigenous communities and digital technologies,Mark Turin, chair of the First Nations and Endangered Languages Program at the University of British Columbia, mentioned the conclusions of a 2007 study of aboriginal language communities in Canada led by Darcy Hallett. Hallett, now an associate professor of psychology at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, discovered that “youth suicide rates effectively dropped to zero in those few communities in which at least half the band members reported a conversational knowledge of their own ‘Native’ language.”

Kayla Begay, a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe in northern California, and assistant professor of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University, said that the finding confirmed what many Native Americans have long believed: “Our overall health and wellness can be helped by returning to our culture and language. We’ve always known it. We’ve felt it.”

Begay works as a consultant on language programs in both Hoopa, which has fewer than 10 fluent speakers, and the related language of Wailaki, which has none. Hoopa is being taught to preschoolers in a Head Start program, as well as to high school students, by trained teachers assisted by the fluent speakers and archival documentation. Begay said that her generation’s goal is “to bring these languages back into our home again, and speak them to our children, and have our children be bilingual. That’s when we know we’ve done something for our language.”

At the conference, “we’re talking a lot about how languages are documented and put into archives here. But the language itself—you can think of it as an archive,” she said. “The languages themselves are a wealth of knowledge about how our people view the world, interact with the world, interact with each other. And that’s of value to our people still. It’s a matter of survival still.”

—Julia M. Klein