Class of ’64 | For most of her life, Ruth Lande Shuman CW’64 has had two grand, overarching passions.

One is for helping troubled and underprivileged teenagers. The other is color—part of an aesthetic that has taken many forms: from studying art and architecture at Penn, to the beginnings of a master’s degree in art history (which she abandoned because it “felt too elitist”), to helping to develop the Big Apple Circus, to earning a master’s degree in industrial design at Pratt, to undertaking an independent study on the psychological effects of color.

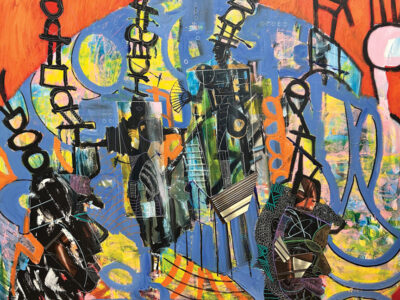

Marrying those two passions, so to speak, would seem an impossible dream. But in fact, Shuman has created a program that has helped thousands of kids in struggling schools in New York by organizing them and teaching them to paint—by coating their own schools and community centers in warm, vibrant, uplifting colors. The program is Publicolor, and it bills itself—with good reason—as a “catalyst for change.”

Having discovered through her independent study that color has “enormous power to change attitudes and energy level,” and being concerned about the rising high-school dropout rate and how that could affect the country, Shuman had an idea: “We could just go into these low-performing schools that look like prisons—depressing and even hostile environments—organize students, teachers, and using beautiful colors, change the way the school looks and feels. It could have a huge impact on teacher and student attendance.”

To a jaded outsider, that might sound wildly idealistic, even naïve. In fact, she was onto something big.

First stop back in 1995 was Junior High School 99 in East Harlem. Drawing on 350 volunteers from the school’s faculty and student body and their sponsor, the Estée Lauder Companies, they painted nearly 40,000 square feet of halls and stairwells.

“The results were enormous,” Shuman recalls.

Next was Central High School in Newark, where Shuman “changed the paradigm and made the program much more student-centric,” transforming it into an after-school program. She admits that she knew “nothing about schools or programs” at that point, but she quickly learned.

“Teachers told me that the program was keeping kids from dropping out,” she says. “It also created a sense of community in a building that had been ravaged. There had been a huge riot between the African Americans and the Haitians. I made a deliberate effort to bring together every ethnic group, and there was not one intercultural incident. It was really powerful.”

Since then, Shuman and the swelling ranks of students and volunteers who comprise Publicolor have painted some 50 schools and an equal number of neighborhood facilities. While students get to choose from a palette of 16 colors, she and the school in question have the final say.

“I tell the kids, ‘The school is our client. We’ve got to listen to the client and help the client be more productive,’” she says. “And they understand.”

Publicolor also offers the Color Club, a three-year apprenticeship program that, according to Publicolor’s literature, “helps hone the newly learned marketable painting skills, fosters good work habits, and through weekly career-education workshops, helps our youngsters envision a productive life.” That includes things like helping older kids find part-time jobs, identifying possible colleges they can apply to, helping them fill out applications and access financial aid—even organizing a multi-campus tour.

“We’ve very much become the students’ second family,” says Shuman. “We’ll be in their life for a very long time.”

By teaching kids how to paint, she points out, “we’re also teaching them phenomenally good work habits that are totally transferable to homework as well as the world of work. It fills you with confidence and success and you go on to the next project.”

They also learn the value of things like teamwork and taking initiative and responsibility for work, as well as showing up on time and with a good attitude.

“We’ve noticed that underperforming schools are places of low expectations,” Shuman adds, “and I discovered that wherever you set the bar, young people will meet you there. So why not set it high?”

The effects have been substantial. A 1999 study by Columbia University’s Center for Arts Education confirmed that schools involved in the Publicolor program showed a significant improvement in student behavior and discipline, which led to fewer student suspensions and improved attendance—by teachers as well as students.

In a lot of inner-city communities, Shuman notes, there is a “pervading sense of hopelessness,” which translates into “very few leaders.”

“I want our kids to be leaders,” she says emphatically. “I want them to have hope, vision, direction, focus, determination. So we’re really creating leaders now. We have 66 kids in the Colors Program. They come to us once a week on Saturdays and paint in schools, and also in nearby community facilities. We always paint a community facility near the school to revitalize the neighborhood and encourage residents to paint with us.”

Those include health clinics, senior centers, homeless shelters, centers for abused women and children, and Head Start facilities—not to mention the local police precinct, usually with the help of the police themselves.

“Many precinct houses look horrendous,” Shuman explains. “There’s a major disconnect between the precinct house and the expectation of courtesy, professionalism, and respect that we expect from police. We can really change attitudes and performance. It’s definitely affecting police-community relations in a positive way.”

Shuman wants to expand the Publicolor program to other cities, and is mindful of the need to oversee that process carefully. Recently, the program has expanded into the realm of animal shelters.

“We thought that if we made these places beautiful destinations, two things would happen: it would affect the mood and attendance and retention of staff, and people would enjoy coming to these facilities—and stay longer and feel good and leave with a pet!” she says. “And so far, the results are bearing this out. At one place, I got a letter from the director of operations, who said that within the first two months, adoption rates skyrocketed!”

Shuman and Publicolor have received a slew of awards, the most prominent being the President’s Service Award in 2000, given by the Points of Light Foundation and presented by President Bill Clinton. And she’s gained even more from the learning experience.

“It’s been such an eye-opener for me,” she says. “I’ve learned so much about the indignities and pressures of poverty. And I feel so good when we go into a health clinic that feels so sad and neglected, and we leave it looking so good and beautiful. The message is so clear: clients are valued and respected. That’s a message that isn’t being felt frequently enough in our underserved communities.”—S.H.