Philadelphia’s NBA franchise has been losing games and fans for most of the last decade. This fall a group of alumni investors led by Joshua Harris W’86 bought the team and have big plans for turning around this troubled asset. Is that crazy?

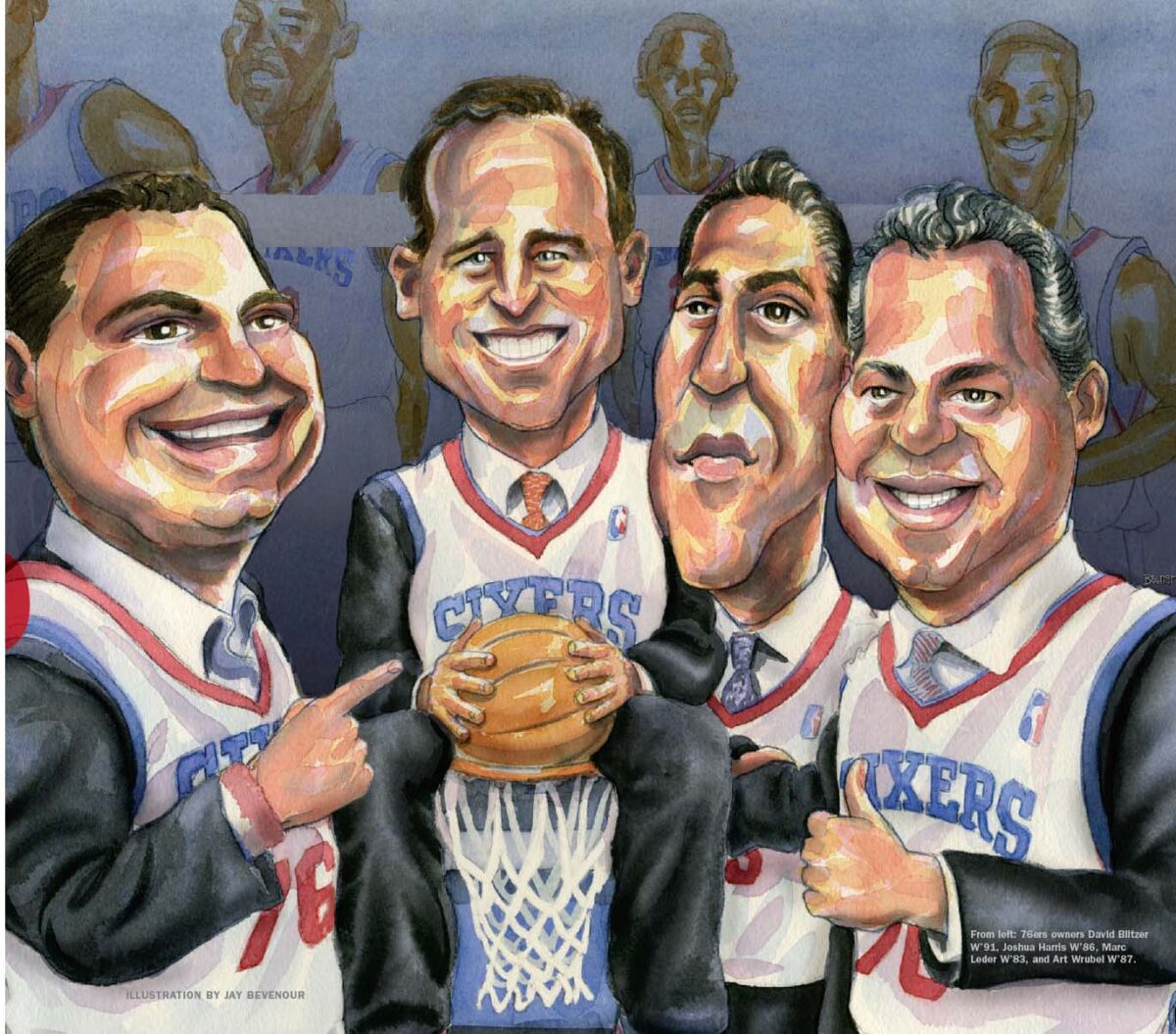

By Dave Zeitlin |Illustration by Jay Bevenour

Save for one older gentleman checking out, it’s a quiet Saturday morning inside the lobby of the Four Seasons Hotel. Cool jazz accompanies the rhythmic drip-drop of a soothing waterfall. There are few other noticeable sounds, not even from outside on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, where cars have yet to emerge from their Friday night slumber.

Upstairs in his suite, Joshua Harris W’86 sits at a long table. A half-eaten bowl of oatmeal and a nearly finished cup of coffee indicate he’s been awake for a bit. Perhaps it was hard for him to sleep. Twelve hours earlier, the Philadelphia 76ers played their first home game of the 2011-12 season, and the rousing fanfare from that night contrasted considerably with the tranquil scene at the hotel the following morning.

“It was,” Harris says with a smile, “a very, very memorable night.”

The game itself was a blowout as the Sixers clobbered the visiting Detroit Pistons by 23 points to continue their strong start to the NBA season. More importantly, the Wells Fargo Center—the team’s home arena—was filled nearly to capacity with fans on hand to see the return of some of the franchise’s legends who were honored before the game, enjoy some of the arena’s new fan-friendly features such as “dollar dog night,” and watch a likable team filled with no superstars but a bevy of promising youngsters.

For a franchise that has seen its popularity and relevance dim in recent years, the game almost seemed like a new dawn. Many fans, for the first time in a long time, were hopeful. And Harris was a big reason for that.

Less than three months earlier, in the midst of a lockout that threatened to cancel the NBA season, Harris and a group of other investors that included fellow Penn alumni David Blitzer W’91, Art Wrubel W’87, and Marc Leder W’83 officially purchased Philadelphia’s NBA franchise from Comcast-Spectacor. (At the time of publication, another Penn graduate, Tony Ignaczak W’86, was also possibly becoming a partial owner, pending league approval.)

Since then, Harris—the team’s managing owner—and his partners have wasted little time trying to restore interest in the once-proud franchise. They hired a new CEO in former travel executive Adam Aron (he didn’t go to Penn but his son does), whose hyperactivity on Twitter engages fans on a whole new level. They started a website called NewSixersOwner.com, where Sixers supporters can offer their feedback on ways to improve the organization. And they slashed ticket prices, added new promotions and improved concessions, all in the hopes of creating a superior game-day atmosphere. Those moves, combined with the confidence the new owners placed in veteran head coach Doug Collins and his cast of young players, created a noticeable basketball buzz in the city, which built to a crescendo for the team’s home opener on January 6.

“We introduced a lot of fan-friendly things at the arena—everything from dollar dogs to giveaways to videos,” says Harris, a New York-based leveraged buyout specialist who says owning the Sixers will basically be his night job. “We’ve tried to engage the city. It was really amazing to see the building nearly full.

“It was almost like going to a party.”

During the game, Harris tried his best to greet many of the partygoers, leaving his owners’ suite to walk around the concourse. A lot of people high-fived him and everybody told him he was doing a great job. Well, almost everybody.

“One thing that stood out is someone told me we ran out of hot dogs, and he was mad at me,” Harris says. “He said, ‘If you’re gonna sell dollar dogs, you’ve got to make sure you don’t run out.’ I said I’d talk to some people about it, and I thanked him for his input.”

The new managing owner of the Philadelphia 76ers laughs, remembering what the semi-disgruntled fan told him next.

“But then he said, ‘Other than that, you’re doing good.’”

Welcome back to Philly, Mr. Harris

Even before he hears the entire question—So, what did your friends and family say about buying the 76ers?—Blitzer spits out his answer: “Are you guys crazy?”

Harris heard the exact same thing from others.

“I talked to a lot of people about it and they said, ‘Are you crazy? You don’t need to do this’” Harris recalls. “And it’s true. Philly fans are well-known as being very passionate.”

By the way Harris says the word passionate, you can tell he’s referring to the love-hate relationship Philadelphia sports fans are notorious for having with their local teams’ players, coaches—and owners. They’ll love you when you win, but they hold you very much accountable if you lose. How he would handle that criticism was certainly a concern.

“I wouldn’t say I was surprised, because I know he likes to take on big challenges and he has incredible stamina,” says Dan Schlager C’86, one of Harris’ old fraternity buddies. “I was more just concerned about whatever negative comments come with being in the public eye.”

There were other concerns, too. For one, the Sixers have not had a winning season since 2004-05, and their average attendance dipped from around 20,000 per game in 2000-01 (when they went to the NBA championship) to under 15,000 last year, one of the lowest in the league. And the outlook for the NBA itself wasn’t too promising, either, with the league’s owners bickering with players over the division of revenue and other issues, which led to a work stoppage that lasted until December and delayed the start of the season.

But as the co-founder of Apollo Global Management, a publicly traded firm that invests in distressed properties, Harris has a history of turning around troubled assets. And he’s always been smart about it, helping transform Apollo from what was once “10 people in a room” into a giant in the investment industry, while achieving the kind of personal wealth he never dreamed possible. In Forbes’ 2011 billionaire rankings, Harris was reported to have a net worth of $1.5 billion.

“People that really know Josh know he’s a thoughtful investor,” says Ignaczak, the president of the private equity firm Quad-C and one of Harris’ best friends since college. “He only gets involved with things he thinks he can have an impact on and be successful at. So I don’t think there was much skepticism among his friends and the people that know him well.”

Like Harris, Blitzer, who serves as co-managing owner, established a successful career in private equity, getting a job at the investment-and-advisory firm Blackstone right after graduating magna cum laude from Wharton in 1991. He’s remained there ever since. “I was ready to go to Penn if they would take me, and I was ready to go Blackstone if they would take me,” he said. “And they both did.”

It was while working in London a couple of years ago—where he established Blackstone’s corporate private-equity investment efforts in Europe—that Blitzer remembers sitting with Harris in an English pub and first talking about buying the Sixers. At the time, it was more of a hypothetical based on his own love for basketball and some rumblings that he’d heard that the team could be on the market. But about a year later, when they found out Comcast-Spectacor was hiring a banker and indeed putting the Sixers up for sale, hypothetical turned into reality.

“It went from a funny conversation in a bar to, ‘They’re really selling this team, and we can really do this,’” Blitzer says.

Blitzer admits Comcast-Spectacor—which also owns the NHL’s Philadelphia Flyers and the Wells Fargo Center—was originally skeptical that a group of private investors led by him and Harris would be able to meet their demands on price. Carving out the 76ers from the rest of Comcast-Spectacor’s entities was also a difficult process that “took significant amounts of time, detail, and focus from everybody,” Blitzer says. But after long and grueling negotiations, the Harris/Blitzer group signed the deal for a reported $280 million early last summer. After completing another long process to get NBA approval, the transaction closed in mid-October, with the NBA lockout in full swing.

“That was a very important issue that added complexity to the whole thing,” Harris says of the lockout. “It wasn’t good, but we factored it into our thinking as to how we created the deal.”

Perhaps the smoothest part of the acquisition was how easy it was to find fellow investors. Initially, Harris brought along one of his best friends from Penn in Wrubel, while Blitzer brought along sports agent Jason Levien. Leder—who graduated from Penn three years before Harris but later got to know him through his friend and Apollo co-founder Marc Rowan W’84 WG’85—told Harris he would like to coinvest as soon as he read about the possible sale in the papers. Other investors flocked in, too, and by the time the sale was finalized, the group included, among others, GSI Commerce CEO Michael Rubin, and Philly-born Hollywood star Will Smith.

“We didn’t ever have to solicit any investors,” Harris says. “They literally came to us.”

Each investor, of course, had his own reason for wanting to buy a stake of the team. But, it seems, there was one motive that linked them all: the confidence they had in Harris, a man who’s never backed down from a challenge.

Like many college freshmen, Harris plastered his dorm room wall with pictures. Only his were a little different than most. “He cut 40 pounds with pictures of burgers and pizza and spaghetti on his wall,” says Schlager, who met Harris the first week of college and later pledged the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity with him. “That shows tremendous willpower right there.”

Harris cut weight because he wrestled in the 118-pound weight class on Penn’s varsity wrestling team, where he remembers his record being slightly below .500. He ended up quitting the squad after his first season because he said staying at such a low weight put “too much of a dent in my college life.” But his determination and competitiveness poked through in other ways. Like when he and Schlager wrestled in the fraternity house and, according to Schlager, “absolutely destroyed rooms.” Or the couple times a week they played pickup hoops at Hutchinson Gym. “He’s not the best ballhandler,” says Schlager, who today runs a conservation investment company in Colorado. “But if you feed him on the wing, he can hit the layup.”

Harris showed a similar kind of drive away from the gym, and it was that work ethic, his friends say, that launched a career that began at the now-defunct investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert and continued at Apollo after Drexel folded (with a stint at Harvard Business School in between). “I think the biggest thing I learned from him is how hard he works and how he’ll do whatever it takes to learn something and be successful at it,” Schlager says. Ignaczak, who was also in SAE with Harris, agrees with that assessment, saying, “My first impression—and lasting impression—was that he was so focused and such a hard-worker.”

Like Schlager and Ignaczak, Wrubel first met Harris during his undergraduate days at Penn and has remained great friends with him ever since. They work out together. They play tennis against each other. They go on ski trips. “I spend as much time with him,” Wrubel says, “as I do with my own family.”

And as both climbed their way up through the investment world, Wrubel marveled at the way his best friend handled his business. “He’s a bright guy, but there are a lot of bright guys,” says Wrubel, a portfolio manager at real-estate-focused hedge fund Wesley Capital. “What separates Josh is his tenacity. He’s a very, very tenacious guy. I think the combination of being tenacious and thoughtful is unique.”

Harris’ best qualities were on full display last November when he ran the Philadelphia Marathon. He says it was his way of connecting with the city—finishing the race in a personal best time of three hours, 48 minutes, and 10 seconds was an added bonus. Yet it was hardly surprising. Whether running on city streets or running a business, raising his five children with his wife Marjorie or keeping old friends connected by planning vacations, Harris’ endurance has always been remarkable. Or, as Ignaczak puts it, “Josh can handle anything.”

But even though he put himself in the spotlight by running in the marathon, Harris doesn’t plan on making the story about him very often. He’s not going to become a notorious referee-criticizer like eccentric Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, or rappel from the rafters like former Sixers head honcho Pat Croce. As thoughtful as he is with his business acquisitions, that’s how thoughtful he is when talking to the media. Sometimes, he appears guarded, and perhaps even reluctant to admit that he grew up rooting for the Washington Bullets and is a “reformed Yankees fan,” instead focusing on how his freshman year at Penn coincided with the 76ers’ 1982-83 championship season. And he’s never loud or boisterous, even when the microphone is in front of him and the cameras trained on him.

“I think I’m sort of a lowkey person,” Harris admits. “It’s something I’m working on.”

Well, in some ways he’s lowkey. When it comes to watching the Sixers, Harris admits he’s turned into a “turbo-charged fan” who watches every minute of every game and “takes the losses really hard.” That makes sense, of course, because losing is not something he’s used to.

Says Wrubel, “He’s just a winner, man.”

Wrubel is breathless just thinking about the day: October 18. That’s when he and the rest of the new Sixers owners were unveiled at a Palestra press conference. And although the day itself was mostly a blur, Wrubel remembers thinking one thing throughout: How did this happen?

“I have a suit on, I’m standing center court at the Palestra and saw all sorts of Penn people and all sorts of Sixers things,” Wrubel recalls. “And I thought, ‘Oh my God, we own the Philadelphia 76ers.’ When it hit me, it was the most humbling thing of all time.”

For Wrubel, this was more than just a business transaction. It was the culmination of a lifelong addiction to basketball. A self-admitted NBA junkie, Wrubel owned the entire basketball-card collection for the 1971-72, 1972-73, 1973-74 seasons. He idolized players like Walt Frazier, Bernard King, Andrew Toney, and Julius “Dr. J” Erving. And, perhaps most important to Philly fans, he loved the Sixers and hated the Boston Celtics.

“Everyone has their own thing,” says Wrubel, who grew up in Connecticut. “For me, I’m a giant basketball fan.”

Wrubel’s hoops obsession never waned into adulthood. Today, he says he can recite the starting lineup for every team in the league and can talk about the sport’s nuances “until I bore somebody.” So owning the same team where Dr. J once soared has a coolness and panache to it, he says, beyond what the financial opportunities may offer. And being a superfan-turned-owner has already proved advantageous. At an early-season viewing party, Wrubel met a 50-something-year-old Philadelphian who introduced himself as “the guy with the worst seats in the entire Wells Fargo Center.” At the home opener, Wrubel ran into the same fan on the escalator and invited him down to sit courtside with him, in part because of his appreciation for the dedicated fans who sit in the nosebleeds.

As insignificant as giving better seats to one person for one game may seem in the big picture, it’s those kinds of little things that the owners have pushed since taking over. At the 76ers-Knicks game at Madison Square Garden on January 11, Leder sat with Aron, who he said tweeted with fans literally the entire night. And they’ve listened to their fans’ demands. At the urging of many, for instance, the owners decided to replace “Hip Hop,” the acrobatic rabbit team mascot who tended to scare children more than excite them. (The official release announcing the non-beloved rabbit’s departure noted he got married and moved away to start a family.)

Why is it so important to push fan interaction to a whole new level?

“Because we are fans,” Blitzer says. “Put yourself in the same position. As a fan of both the Sixers and sports in general, the experience overall is extremely important to us. Frankly, one of the first orders of business was to really push on social media and push on fan engagement.”

When it comes to being a fan, Blitzer is one of the few people who might be able to compete with Wrubel’s passion. Growing up in New Jersey, he played almost every sport available but, like many, quickly realized he was never going to make it as an athlete beyond high school. Instead, he devoured the local pro-sports scene, going to Stanley Cup finals games for the Rangers and World Series games for the Yankees in the 1970s. He remembers attending his first basketball game when he was about seven years old to see the New Jersey Nets, then of the American Basketball Association. But like Wrubel and the other owners, he always appreciated individual basketball players more than teams, admitting he was a “complete Dr. J disciple.”

As he got older, Blitzer tried to understand more about the business of sports and wrote a thesis at Penn about free agency and the labor market in sports. So when he “got lucky enough to be in a position where he could invest in the Philadelphia 76ers,” he says, it was a perfect merger of his lifelong passion with his business acumen. And even if some people asked if he was crazy, perhaps the person that knows him best understood just how much the acquisition made sense.

“I actually went to my mom for approval,” Blitzer says. “And she’s sort of a conservative person. But she just chuckled and said, ‘You know, if you ever told me you’d do something as crazy as this, this would actually be the one thing that wouldn’t shock me. You’ve wanted to invest in a sports franchise since you were five years old.’”

Steve Bilsky W’71, the former standout point guard at Penn and the school’s current athletic director, can be spotted at the Palestra just about every time his alma mater plays a men’s basketball game. But going to the Wells Fargo Center is another story.

“In terms of teams, I would put the Eagles and the Phillies and the Flyers ahead of the Sixers,” Bilsky says. “Now I’m thinking of going to a Sixers game as soon as I can.”

Why the change of heart? Well, for starters, the way this particular 76ers team is constructed is satisfying for people like Bilsky who enjoy “watching good basketball rather than a bunch of dunks and superstars.” And, of course, the Penn connection is one that has the athletic director very hopeful about the direction of the city’s NBA franchise.

Even before the new ownership group took control, Bilsky got the chance to speak with Harris and Aron, and was immediately impressed with their desire to reach out to Penn. The Sixers owners have since followed through on that commitment by holding the introductory press conference—and later an open practice—at the Palestra.

“Those things are not accidental,” Bilsky says. “It wasn’t like they were looking for a place to have the press conference. They wanted to make a statement by having it at the Palestra—both by reaching out to the community and reestablishing their Penn ties.”

Vince Curran EAS’92 W’92, a former player and current radio commentator for the Quakers, has become very friendly with some of the new owners, particularly Wrubel. And he’s seen firsthand the connection they’re trying to foster with their alma mater.

“The thing that strikes me about the new Sixers ownership group is that they are loyal Penn people through and through,” Curran says. “It was very important for them to reconnect to the University when they came back to town. They’re going to be active here. To have loyal Penn people like that around that great organization, and combine that with our great institution, I think it’s going to be a win-win for everybody.”

At this point, it’s not entirely determined in what ways the Sixers-Penn relationship will develop. Bilsky said the Penn band may play at an upcoming Sixers game, and Curran noted that job opportunities and internship programs could pop up for Penn students and graduates. But most of the owners admit they’re still in early stages of talks with the University.

Whatever the case may be, it doesn’t seem likely that the owners will ever lose sight of their Penn ties. For some, the school has been in their blood since they were born. Harris and Wrubel’s fathers went to Penn. So did Blitzer’s two older siblings. Pending owner Ignaczak’s son was recently accepted here. And since graduating, they’ve remained involved with their alma mater as Harris, Wrubel, and Ignaczak all serve on the Wharton Undergraduate Executive Board and Leder on the Huntsman Program Advisory Board.

“I think Penn does a great job building relationships with their students while we attend school, and even more so once we graduate,” says Leder, who left a job at Lehman Brothers in 1995 to start the private investment firm Sun Capital Partners, Inc. with former classmate Rodger Krouse W’83. “It feels like a large, extended family. I have a lot of friends who went to school in Boston or Washington or LA, and they graduate and move to wherever they’re going to live and they don’t give their school or city another thought.”

Wrubel, who called going to Penn “the single most transformative thing I ever did,” says that the “whole notion of coming back and giving back to the area was really cool.” And it’s only gotten cooler for them to see the Sixers get off to their best start in nearly a decade and ascend to first place in the Eastern Conference.

From here, the goals for the new ownership group are clear. They want the Sixers to continue their on-court success and for fans to pack the arena as they once did. They want the team to be a perennial championship contender as they once were. And, yes, they want their investments to be profitable in the long run.

But there is more to it than that. When asked what they hoped to get out of it, all of them talked about having fun with old classmates—in the shadow of the school that shaped them—and cheering on their new favorite team with their families. In that regard, they’ve already enjoyed many goosebump moments. Here’s one:

At the home opener, Wrubel sat with his 10-year-old daughter Ava (“a nutball about basketball,” he says) at the scorers’ table. Ava was wearing a Jrue Holiday jersey. Holiday, perhaps the best player on the Sixers, approached the scorers’ table from the bench, saw the young girl in the jersey and winked at her. When it was time for him to check into the game, he bent over and put his hand behind his back, like he was ready to take a relay baton. Ava slapped his hand. Holiday sprinted into the game. Ava’s smile stretched to the rafters. So did her father’s.

“I never thought any of this would happen to me,” Wrubel says. “Here I am, a partner in an ownership group that owns the Philadelphia 76ers, with a lot of my friends. I feel like a little kid.”

Dave Zeitlin C’03 contributes frequently to the Gazette and oversees the magazine’s sports blog.