In 1988 James Martin W’82 jumped off the corporate fast track at General Electric to become a Jesuit priest. That meant two decades of study and service; taking vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience; and praying a lot—oh, and also living rent-free in midtown Manhattan (in the same building where he works!), writing bestselling books, and palling around with Stephen Colbert.

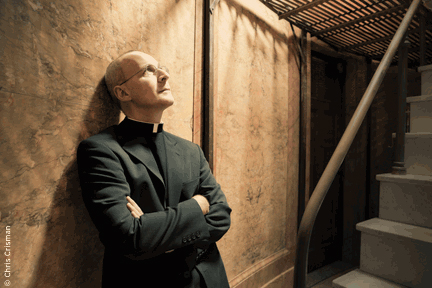

By Alyson Krueger | Photography by Chris Crisman C’03

With a full heart and a steady focus, Rev. James Martin, SJ, kneels beside the twin bed—immaculately made, with crisp white sheets—in his room at the Jesuit house, clasps his nervous hands, and prays: Please God, don’t let me screw up tonight on The Colbert Report. Okay, those weren’t his exact words. His exact words were a quote from the psalms: “Lord, open my lips and my mouth shall declare your praise.”

Martin has given up sex, material goods, and a very considerable amount of independence to become one of God’s spokesmen on Earth, but he still doubts whether the big man will listen to his pleas alone. So he turns to Facebook. “If you have a second,” he asks his then-2,651 friends, “pray that I don’t accidentally say anything (a) dumb, (b) offensive, (c) inarticulate, (d) inaccurate, or (e) heterodox tonight.”

He should have added: Prevent me from committing the unforgiveable sin of being funnier than Stephen Colbert. This is his sixth appearance on the show (his official title is The Chaplain of the Colbert Nation), and in the past he’s come close. Last time, he said shit on national television. (Colbert and his audience was amused; a few of his Jesuit superiors less so, even though it was bleeped.) On another night, he told Colbert he would make him a saint (who knew it was so easy?). And after winning an argument about whether Mother Teresa is in hell—um, not!—he shrugged and pointed out, “Well you did ask a Jesuit on the show.”

This time Martin is appearing to promote his ninth book, Between Heaven and Mirth: Why Joy, Humor, and Laughter Are at the Heart of the Spiritual Life. (He considered titling it, “Jesus, That’s Funny,” but that didn’t go over well at base camp.) There is little he can do to prepare for Colbert. He doesn’t need to go over the material: “If I don’t know it after 22 years, I’m in trouble,” he says. He doesn’t need to choose his outfit. Jesuit priests have a uniform: black suit, white clerical collar. He doesn’t even need to comb his hair. At 50, he’s mostly bald.

Still, when I meet Martin at the Jesuit house at 106 W. 56th Street—a nine-story building that also contains the offices of America, the national Catholic weekly magazine, where Martin is culture editor—to escort him to the show, he is nervous. I am five minutes early, but he is at the door waiting for me. “You dressed up for the show,” he says approvingly. “We look sort of similar.” We do. Priest garb, little black dress, same thing.

Staying true to his Jesuit vow of poverty, Martin declines the town car and driver Colbert provides for his guests, so we trudge the mile or so to the Colbert studio on 11th Avenue, where a line of ticket-holders is wrapped around the dreary corner. When we get into the lobby, Martin is no longer paying attention to me. A Colbert intern greets him excitedly, “Hello Father!” And the receptionist welcomes him as an old friend. “Your mother and sister are here,” she says, ushering him into the downstairs green room reserved for the featured guest. “Your sister baked.”

That is an understatement. Martin’s younger sister Carolyn, a Harvard grad and career consultant, made at least four tins of chocolate cupcakes, cookies with some type of marshmallow center, and sugar cookies for the production staff. “Is she trying to sweeten up Colbert, so he won’t be harsh on you?” I ask. After all, Colbert has a team of hysterical writers on his side, and well, you have no one, I suggest. That is not true, Martin informs me, breaking into a huge, boyish grin. “I have Jesus.”

Well then.

James Martin is not your regular priest. Oh sure, you can find him celebrating Mass on various Sundays at the imposing grand altar of the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola—founder of the Jesuits—at 84th and Park. But you are far more likely to spot Martin in his role as New York’s preeminent celebrity priest. Paid speaking engagements and sold-out lectures? Check. Book signings and The New York Times bestseller list? Check. Recognized in restaurants and on the street? Yep. Martin is so attuned to his celebrity that once when a female friend tried to hold his hand walking down Broadway, he pushed it away, cautioning her that he must not do such a thing with his collar on. Even when he takes a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, he posts regular dispatches to his Facebook page—including a report on the inflight movie (Bridesmaids) on his way to the Sea of Galilee. And then there is Colbert, his new BFF, who reached out to him after reading one of his Times opinion pieces on Mother Teresa and elevated Martin to basic-cable stardom.

Martin’s most regular outlet is his position as culture editor of America, which he describes as “the Atlantic” of the Catholic world. There he regularly opines on everything from gays in the priesthood (misunderstood) to the sainthood of Steve Jobs (probably not). When the Penn State scandal broke, he was invited to offer “a priest’s view” for The Washington Post. He also writes, on occasion, for the Times op-ed page. He does at least five interviews a week for outlets such as NPR, CNN, PBS, BBC, and The History Channel.

Of his nine books, two have been bestsellers. Martin estimates that his book sales and speaking engagements combined have brought in more than $500,000, all of which goes to the Jesuits, of course. Which is one reason that, except for his saying shit on the Colbert show, even the Church hierarchy—he is still giddy over a letter from the Superior General of the Jesuits praising his work—is cool with Martin.

As Father Martin will tell you, God works in mysterious ways. Why else would He have sent Jim Martin to the Wharton School of Business first? God, you clever dude! To create a priest with such excellent marketing skills.

Martin’s second book was a memoir he wrote while he was a priest-in-training called In Good Company. Published in 2000, it chronicled his journey from corporate America to the priesthood. Kathleen Norris, another bestselling author about Christianity, wrote of the book that, “The world of the Jesuits, which at first is unfamiliar if not downright mysterious, comes to seem a sane way of living in the world, while what we think of as the ‘normal’ world of corporate America is revealed as very strange indeed.”

Yes, 30 years ago, Martin was a fast-track executive at General Electric, in the hard-driving heyday of Winning author Jack Welch. Every morning his alarm would wake him at 7 a.m. “on-the-dot” so he could brush his teeth, comb his hair (back then he had hair), put on his Brooks Brothers uniform (he had a set of pin-stripes and a set of solids) and walk from his Upper East Side apartment to his glossy midtown office to arrive at 9 a.m. “on-the-dot.”

He didn’t love the work. He found he was neither interested in nor passionate about number-crunching and spreadsheet-assembling. But he enjoyed his colleagues and liked having a large sum of money to throw away on beers at P.J. Clarke’s and bottle service at The Pyramid Club, where one memorable night the “performance” consisted of a woman throwing raw chicken parts at the audience. More important, he was doing exactly what he was expected to do. Martin’s parents, a marketer for a pharmaceutical company and a substitute French teacher, had been “delighted” that he went to Wharton, says Martin. “It meant that I would have a secure financial future.”

Even as an undergrad, though, Martin showed signs of being interested in things other than money. He’d quiz his friends in the College about their liberal-arts classes, especially art and art history. He had 4 a.m. conversations about the existence of God and the meaning of life. He lived in an off-campus house on Spruce Streetwith 15 other students, which had its own theme song—Bruce Springsteen’s “Rosalita”—and put together lavish theme parties (Black & White, Art Deco, the Last Dance, and so on) that required a significant amount of creativity. (They also took time for the occasional staged photo—see opposite page.)

“I didn’t really know what I wanted to do,” Martin recalls of himself then. “Wharton, as the best undergraduate business school, seemed appealing. I thought I could at least do something with that, get into the business end. I used to say that all the time ‘the business end’ of writing, or the ‘business end’ of art. I used to enjoy painting and art—so I thought perhaps museum management. But I only had the vaguest idea of what I wanted to do.”

An important step on his road to the priesthood occurred during his time at Penn, after his friend Brad Almeda C’81 was killed in a car accident the summer after their junior year. Almeda, a communications student and wrestler whom one classmate calls “the Adonis,” had been Martin’s freshman year roommate in the Quad. Nubile coeds would find excuses to walk by their room, just to catch a glimpse of him—but what they usually got instead was a joke or two from Jim Martin. Martin was devastated by Almeda’s death. Back on campus a group of students, angry and confused, gathered to talk about how God could possibly do this. Martin was among the angriest. A quiet, devout girl named Jacque Braman W’82 (now Jacque Braman Follmer) offered a comment: “I just thank God for the time we had with him.” That moment changed the way Martin viewed religion. From that moment on he wanted God to be his buddy, not someone he feared.

It was this James Martin who became increasingly frustrated at General Electric. “It is one thing to want to change jobs,” he says. “But it’s another thing to feel like you are in a completely wrong place.” While his colleagues worked long hours trying to prove themselves and get promoted, Martin lacked the competitive drive to do well in this field. At GE he found a strict boss who made him do things he was not comfortable with—like tweak numbers in official records. In Good Company chronicles that corruption as well, which would, years later, lead to a Securities Exchange Commission investigation and a $50 million settlement. Ultimately, he switched to a human-resources job with the company in Connecticut, hoping it wouldn’t be as cutthroat. But Connecticut was cutthroat, too. Ultimately, six years of General Electric gave Martin anxiety-related stomach problems, so he decided to see a therapist (If GE is paying for it, why not, he reasoned). The therapist asked him, if he could do anything in the world, what would it be? “That’s easy,” Martin answered. “I would be a Jesuit priest.”

This announcement apparently came out of nowhere. Martin had never even hinted to those who knew him that anything was awry at GE, let alone that he fancied being a priest. And the reaction from his friends and family was anything but supportive, he recalls. When he told Chris Brown, one of his best friends at GE, that he was thinking of going into the priesthood, Brown replied, “You need to see a therapist.” When Martin said he already had one, his friend said, “Then you need to see another one.”

His parents, after he made a pilgrimage home to the Philadelphia suburb of Plymouth Meeting to tell them his intentions, basically said, “Are you nuts? What about all that Wharton education? Are you just going to waste it?” And it was more than that. Catholics are notorious, Martin notes, for worshipping priests—until their son decides to become one.

To hear Martin tell it, his big epiphany had come one night in 1986 when, exhausted from his day at GE, he was sitting on his sofa channel surfing. He happened to catch a PBS documentary on Thomas Merton, the 20th century Trappist monk, who lived in a monastery in (yes) Trappist, Kentucky, and spent much of his days and nights writing about spirituality and peace—two things that had eluded Jim Martin at GE. “Everything about that documentary seemed to offer me ‘another way,’” Martin explains.

Most important, Merton liked his life: “The look, at least in the photographs, showed a kind of happiness and contentment that was unknown to me.” Martin became convinced that this was God calling him to the priesthood.

It would have made total sense that if God was calling Jim Martin to the fold, he also knew what brand of priest he would be. Of course he’d be a Jesuit! The intellectual division. But in fact, finding the Jesuits (officially, the Society of Jesus) was a fluke. “I literally, literally did more research on what car to buy,” he insists.

Having moved to Connecticut when he took the HR job, Martin approached his local priest, Fr. Bill Donovan at the Church of St. Leo’s in Stamford, and confessed his desire to join the priesthood. Donovan advised him to check out the Jesuits, who lived and worked at Fairfield University “down the road.” After meeting with the Jesuit recruitment committee, reading four books (including one “sort of nutty book which tells all these tales about Jesuit intrigue”), and going on an eight-day retreat at the Campion Renewal Center in Weston, Massachusetts, he was sold.

Sold on the following: By signing up to be a Jesuit, Martin would have to commit to 11 years—11 years!—of study before he could be ordained as a priest and another 10 before final vows. And he thought Wharton was tough. There were two years of philosophy studies at Loyola University Chicago, and two theology degrees from Boston College. And service. Years and years and years of service. In East Africa, he helped refugees start small businesses and co-founded a handicraft shop, while staving off a two-month bout of mono, and feeling lonely, deserted, and scared for his life (the subject of his first book, This Our Exile: A Spiritual Journey with the Refugees of East Africa, originally published in 1999 and reissued last year.) In Kingston, Jamaica, he comforted dying men at a hospice, bathing and shaving them in their last days. In Boston, he worked at a homeless shelter and as a chaplain in a prison.

Through his training he lived in austere conditions. A Penn friend, Ellen Edelman Weber W’82, remembers that Martin passed up a Bruce Springsteen concert because he couldn’t afford to travel to the venue, let alone buy a ticket. “In the early days the poverty vow was very evident,” she says. “If we wanted him to do something with us … he couldn’t pay.” With a monthly allowance—or personalia, as the Jesuits call it—of $35 a month, he could barely afford a night out for a beer. (Today, his allowance is $300 a month.)

And there was excruciating introspection. During one early session with the Jesuit in charge of recruiting, the priest asked him question after question about his sexual preferences, fantasies, and even masturbation before saying, “Do you mind if I ask you a few personal questions?” Another time, about 15 years ago, he fell deeply in love with someone. It was a “pretty stormy time,” Martin admits, which required a deep evaluation. Did he really want to do this?

At every stage, despite the challenges, Martin answered yes. “I really was so happy,” he says of his priest-in-training years. “It was just amazing to go from a place where I thought, ‘What am I doing here?’ to be in a place where I said, ‘I can’t believe I’m here!’”

On November 1, 2009, in front of his close family, friends, and God, Father James Martin took his final vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, as a “fully professed” Jesuit. Before the ceremony he had a mix of emotions, “probably the same way a groom does.” Hmm. “Did you get a bachelor party at least?” I ask.

“Uh, definitely not.”

There are no lights on in all of Briarcliff Manor, New York—or at least it seems that way, in this sedate village near Rye, 25 minutes from the city, the kind of pristine suburb where some of Jim Martin’s old pals from GE built their dream homes before the recession hit. It’s so quiet and subdued, you can’t help but wonder if they’re all in foreclosure.

Then you see, up on a hill, the sparkling castle that is the Parish Church of St. Theresa, the patron saint of headache sufferers. And then there is light! Vivid colors beam from the stained-glass windows. The crowd is so large it takes three parking lots to accommodate all the cars; inside, it’s standing room only.

And there is laughter, already emanating from St. Theresa’s. Not polite chuckles meant kindly for your religious leader, but knee-slapping, tear-inducing laughter. Jim Martin is here, to speak about finding humor and joy in the Catholic Church. Who knew?

Father Martin, who arrived fashionably late, is telling a joke: A journalist visited Blessed Pope John XXIII and asked, “Your Holiness, how many people work in the Vatican?” John replied, “About half of them.”

Ba-da-boom.

The crowd roars. Without missing a beat Martin adds, “Oh and by the way, if you haven’t picked up my new book yet, they are for sale in the back.”

Later that night, after his fans in Rye have bombarded him for autographs, Jim Martin returns to his room at the Jesuit house with its modest twin bed and a crucifix hanging on the wall. Can you get a bigger bed? I ask. “Yes” he replies, “but it would just remind you more of chastity.”

Downstairs, in the sprawling kitchen, two full-time chefs make two meals a day and there is a pantry full of Raisin Bran, peanut butter, and coffee. Brother Frank Turnbull, one of Martin’s housemates, who has been a Jesuit for 50 years, says about their lifestyle, “You can’t beat it.”

The Jesuits even provide his living companions: 19 (much) older priests who are very accomplished—there are writers, architects, and former college presidents in the mix—but go to bed at 9 o’clock (“You’re not living so much with your brothers, but your fathers,” Martin cracks). When they aren’t in bed, they hang out in the sixth-floor sitting room, which sort of looks like a nursing home with bare walls and old padded armchairs. But there is an open bar! It is customary, between Mass and dinner, to repair to the sitting room for a couple of drinks.

There are some rules. When Martin needs to make any big purchases, he must go to the powers that be for approval. On one day recently he is particularly excited because he just got the OK to buy a new suit and when he went to Jos. A. Banks there was a buy-one, get-two-free deal. One of his old Penn friends, determined not to send him another crucifix for his ordination, sent him a gift certificate to Banana Republic. He was delighted to be able to buy pants without permission.

But in fact, the Jesuits provide almost every worldly good he could possibly need, and will for eternity—from his food to his socks to his toothpaste to his final resting place (he’ll be with his bros at the Jesuit cemetery in Weston, Massachusetts, at the same place he made his first retreat). Not to mention the sweet piece of real estate in midtown Manhattan that he calls home, and that is the envy of many of his friends who actually have to pay their own mortgages. It sort of takes the edge off the vow of poverty.

His Wharton classmate Weber points out that while many of their mutual friends lost money and opportunities in the economic crash, Martin was safeguarded. Both from money problems and the emotional toll. “It’s actually very freeing,” says Martin. “I don’t really think about money too much because I don’t really see it.”

And he couldn’t have an easier commute. On the second floor of the house is the headquarters of America, where Martin pens his columns. One controversial issue where there seems to be a fair amount of daylight between his views and the hierarchy’s position is homosexuality and the church. “Officially at least, the gay Catholic seems set up to a lead a lonely, loveless, secretive life,” Martin wrote on the magazine’s website (www.americamagazine.org). “Is this what God desires for the gay person?” After the Vatican issued a document banning gays from the priesthood, Martin clarified the implications in a comment to a New York Times reporter: “It’s a clear statement by the Vatican that gay men are not welcome in seminaries and religious orders.” Asked how he would respond to gay marriage if he were Pope (the current hierarchy, Martin says, will “not change its teaching one bit”) his response was, “No comment.”

Another subject he doesn’t shy away from is the Church’s sex-abuse scandal. The problem, says Martin, is not that the priesthood attracts weirdos. He points out that a lot of abuse takes place in schools and families. (“You would never say, what is it about marriage that attracts perverts, right?” he says.) But he feels strongly that the Church did not act fast enough to get rid of “these guys.” And it was not transparent. “A lot of decisions were made behind closed doors, and transparency and openness about finances and the operation of the Church is really essential.”

No one who reads Martin’s writing would be unsure of his views. “Any intelligent person would probably understand his deep feelings,” says Susan Melle, a former colleague at GE and practicing Catholic, but he still has to toe a careful line. A select few of his superiors (they are called censors, which is where the word comes from) approve everything he writes before it is published, especially his books, which are marked with the Latin phrase, imprimi potest, which means, “It can be printed.” Accepting this scrutiny, something he does as part of the vow of obedience, is one of the hardest parts of being a Jesuit, he says.

“You are such a big brand,” I tell Martin, a few days before the Colbert show. “You have all these books, you can do whatever you want.”

“Thanks to the Society of Jesus,” he interrupts. “I wasn’t doing this before I was in the Society of Jesus.”

“But you could have been.” Wharton-educated, naturally talented writer and speaker, Hel-LO!

“No I couldn’t have been. All the experiences I write about, all the stuff about prayer and spirituality and the saints and humor; I learned all that in the Society of Jesus. They made me who I am.”

Still, why doesn’t he just go off on his own now, become a big star, keep his profits, write without scrutiny, and have lots and lots of sex, which he admits he misses.

He pauses. Then:

“What would I be writing about—GE?” he finally says exasperatedly. “The only reason I wanted to communicate something is because I had something to communicate.”

Something he could never have communicated, apparently, without 21 years of Jesuit training.

Martin does not see his media appearances, book tours, or books and columns as any form of self-promotion. “It’s not about me,” he says. “It’s all to bring people to the books, which bring people to God.” It is the Catholic Church and the Jesuits that awoke his passions and enabled him to use his talents, he says. It’s “all in service of the greater glory of God,” he says, quoting the Jesuit motto.

And he thinks it’s good material. “For Pete’s sake, Christ has risen, after all!” and “You can’t make the Gospel unexciting, I mean you really have to try … It’s revolutionary. It’s radical.”

“Five, four, three, two … ”

The Colbert Report stage manager is ushering Martin in for his sixth appearance on the show, to promote his book about humor in the spiritual life. As he waits on stage, he waves to the crowd, shoots a wide grin, and then makes the Sign of the Cross. The crowd bursts out laughing, but for the Jesuit priest, this is no joke.

The morning after, Father Martin kneels beside his bed, and says his morning prayers. When he finishes the day’s Scripture readings, he closes his prayer book, and does what any good author would do after a “Colbert bump.”

He makes the sign of the cross, turns on his computer, and checks his Amazon ratings.

Alyson Krueger C’07 is a journalist living in New York.