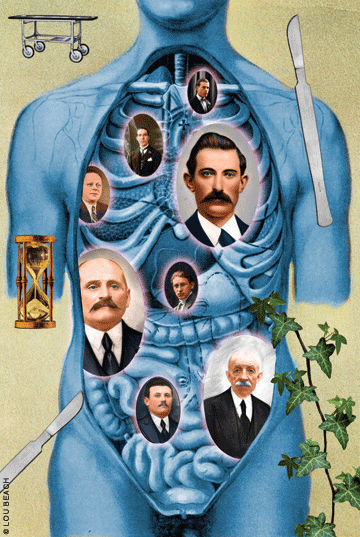

Dissecting the psyche along with the flesh.

By Joshua Fischer

The smell was the first thing we noticed, a pungent cocktail of death and preservative. It hit us as we walked down the hallway on our way to the anatomy lab for the first time. It was a warm, sunny September morning, and 92 of us, first-year medical students all, filed in slowly. Outside it was beautiful, but down here in the lab there were neither windows nor sunlight nor any of the sounds of late summer. Instead, a sterile white light painted the room, and a musty stink filled the air.

Each group of four students stood around their assigned dissection table, waiting awkwardly for direction. Shortly, one of the course leaders approached and called several of us around her. She unzipped the body bag on a neighboring table and, after a few introductory words, made an incision in the cadaver’s arm with her scalpel. An oily goop leaked out from the visible layer of thick, yellow fat beneath the skin. I felt my stomach lurch. The instructor proceeded to stick her gloved hand directly into the fatty mass and pull up a large chunk of flesh, an act that was accompanied by an audible peeling sound as the connective tissue beneath gave way. A few words of encouragement followed, and then we were instructed to return to our own cadavers to begin the day’s dissection.

We had been warned that we would experience strong emotional responses to our cadavers, but assured that these would quickly dissipate. Sure enough, within half an hour we were engrossed in the task at hand, and most of my feelings of timidity vanished. I cut and skinned with nary a second thought, and during our break heartily ate a burrito with one of my lab partners. Just once during that first day I looked for a moment at the outline of my cadaver’s hands, still wrapped in bandages and plastic, and had the realization thrust upon me that this was an actual human being. I thought of those hands cooking a meal, holding a lover, hugging a child, and felt a startling connection to the dead man that lay before me. I imagined a life to accompany the body. I conjured an image of a young man in army uniform, storming a beach at Normandy; a dapper fellow in a 1950s trench coat and fedora hat behind the wheel of a large Buick; a kindly senior citizen surrounded by his grandchildren. I wondered if any of these images corresponded to the actual course of events.

I slept uneasily that night.

The following week a surprise waited as we entered the laboratory for our second dissection: a poster on the wall announcing the age and cause of death for each cadaver. I eagerly approached and scanned the sheet for cadaver number 12. Age: 91. Cause of death: pneumonia. An added bonus came in the discovery that our cadaver’s lungs were filled with black patches, a sign of a lifelong smoking habit. Here was another small fact about my cadaver’s life, and I revised my imagination accordingly. Now, the young GI huddled in a trench smoking a Lucky Strike in the moments before a battle. A smoke dangled from the mouth of the hat-wearing, Buick-driving man, who was beginning to resemble Humphrey Bogart.

By the time our third lab session rolled around, I had become fully engrossed in the daily grind of medical school. Every day brought an almost crushing number of new facts to learn, and my curiosity about my cadaver’s life faded to the back of my mind. I hacked away at skin, connective tissue, and gobs of oozing fat without reservation or disgust—or any other emotion—while my lab partners and I traded jokes and trivial small talk. I began to feel that I was really on my way to becoming a physician. After all, if I could so quickly get used to my cadaver, then surely the other things that seemed daunting about medicine—the sights and smells of horrific wounds, the intense emotions of patients in fear and pain, the specter of death—could also come to seem routine.

Then something truly shocking happened.

One night, as my wife and I were making love, I looked down at the soft skin of her arms and breasts. Suddenly, I could see everything: the cords of the brachial plexus running through her armpit; the arteries coursing through her chest wall; the separated heads of her biceps muscle. The person whom I loved most in the world had in an instant been reduced to a tangled mess of meat. I closed my eyes and clung tightly to the warmth of her body. When I opened them, the moment had passed, but the lesson had not. I understood that my medical education had already begun to change the way in which I perceive the world around me.

For once, I was grateful for the rapid pace of medical education. I threw myself wholeheartedly into studying for an upcoming biochemistry exam and, as my mind became flooded with the details of various metabolic pathways, I found it easy to ignore the emotions that this jarring event had roused inside of me. My next several forays into the anatomy lab were uneventful, and I became content to chalk the experience up to one of life’s odd moments. But there was to be one final episode, several weeks later, to remind me that my evolution from mere mortal to unflappable physician would never, despite the best efforts of the system, be fully complete.

All semester long, we dissected from the neck down. Our cadaver’s heads were kept tightly bandaged and covered in plastic. This was partly to save the head and neck for our future neuro-anatomy course, but also, I suspect, to provide an emotionally easier experience for us students. Thus, as we came to know the inner workings of every aspect of our cadaver’s bodies, the forms of their faces remained hidden from us.

One night, in a dream, I was standing over my cadaver. The plastic bag had been removed from his head, and all that separated his identity from me was the bandage on his face. I hesitated for a moment, aware that what I wanted more than anything was to leave the room, but knowing that I wouldn’t. I felt a chill shimmer down my spine as I saw my own hand reach outward, against my will, to take hold of the bandage, and slowly begin unraveling it. Gradually, the bandage gave way to the decomposing flesh below, and I knew even before I had finished what my investigation would reveal.

The face of my father stared back at me. His early death had been an important catalyst in my later decision to attend medical school. His face had become that of my cadaver, whose skin and fat and organs I had so thoughtlessly helped to hack out, and which lay now in a large, messy pile around the dissection table.

I awoke with a start, sitting bolt upright in bed.

It was an unseasonably warm autumn night, and through my open bedroom window, I felt a refreshing breeze touch my face. Outside I could hear the sound of a bird fluttering overhead. I looked over at my wife. She was sleeping peacefully, her body curled up beneath our blanket. Her stomach moved rhythmically as she took light, sweet, breaths, and I looked on with a sense of peace and reassurance as I saw the outline of her young, pretty face in the moonlight. Inside of me, I felt a sense of love well up, so intense that it was almost palpable. I leaned over and gently, so as not to wake her, kissed her on the forehead, lingering just for a moment to feel the warmth of her life pressed against my lips.

Joshua Fischer GEng’05 is a second-year medical student at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.