Recipe for industrial redevelopment: Take empty grain elevators, add vision.

For years, Rick Smith C’83 worked in the shadow of a cluster of concrete grain elevators in Buffalo. But like many who grew up in the area, he never gave much thought to the hulking relics of an industrial past that had put New York’s second city on the map. Most of them had been abandoned and were deteriorating and splashed with graffiti.

Then one day Conagra Brands, the packaged-food manufacturer that owned three of the elevators, responded to Smith’s request for an easement to accommodate the expansion of his family business by inviting him to check out the elevators.

“The elevators turned out to be way cooler than I thought,” Smith says. “Standing under them, I really got a sense of their castle-like structures and how the river has shaped their geometries.”

Smith learned that the company was looking to unload its 12-acre site altogether. He bit, picking up the land and the elevators for $120,000. It was a great deal, but he didn’t quite know what to do with his new acquisition.

“I was mostly overwhelmed,” he says. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is a lot of stuff!’ The sheer scale, the height, the volume.” The elevators typically rise higher than 150 feet, and each one can hold more than a million bushels of storage.

Today, the chirp of birds hiding in native grasses and the lap-lap-lap of kayakers on the Buffalo River accompany the crunch of gravel underfoot as visitors arrive to enjoy anything from a performance to an art exhibit to a wedding. It’s all part of what the 56-year-old Smith has dubbed Silo City, which operates a thriving performing and visual-arts program and, increasingly, rents itself out for private functions. But that wasn’t originally the plan.

Smith and his partners first latched onto an idea of using the facility to make ethanol. The notion floundered when they discovered that the city’s infrastructure—its rail lines, its natural gas system—might not be up to the task. “Plus,” says Smith, “the neighborhood didn’t really want to become industrial again.”

In 2011, an enthusiastic group of preservationists and architects toured the complex and “confirmed what we had begun thinking,” Smith says. “The conference served as a catalyst to open up the elevators and get people in to see if they liked them.” The next Spring, Boom Days—an annual festival to shoo away winter that Smith and others had created a decade before—moved to Silo City, finding a permanent home.

Then came the artists, at Smith’s invitation. In 2012, a local theater company, Torn Space, staged Motion Picture, using the exterior of one grain elevator as a surface to project both video and light, telling the story of a soldier preparing for and engaging in battle. Other colorful productions have since followed.

Last summer, architecture students at the University of Buffalo created 10 small “reflection spaces” from which to contemplate the silos and their surrounding meadows. Other artists have shot videos and created temporary installations inside the silos themselves; poets and chamber musicians revel in their moodiness and their reverberations.

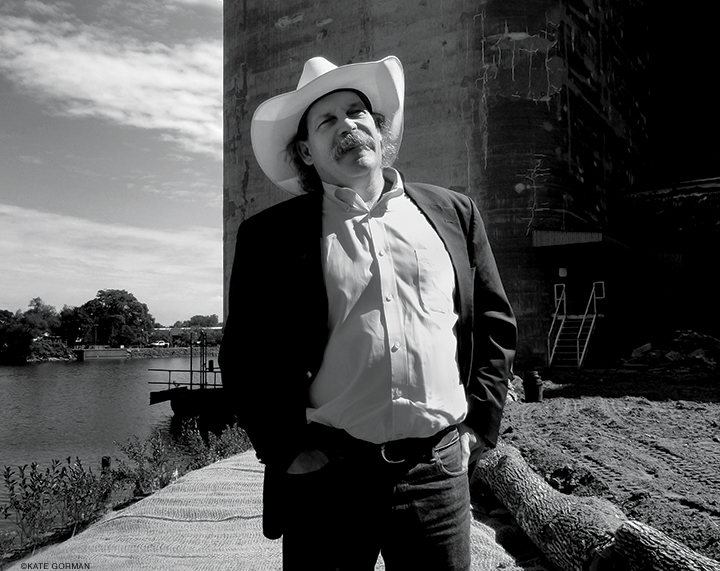

In a way, Smith and the elevators were made for each other, each asset-rich but difficult-to-peg, each in need of a boost. Born in Cleveland, he relocated with his family to Buffalo as a kid and stayed there until college. After graduating from Penn, where he majored in economics, Smith bounced around the globe, working for a safari outfit in South Africa, as a squash pro in Colorado, writing songs in Ireland, and then pursuing a career in music more seriously, putting out four CDs of what he terms “Americana, not country.” Whatever he is, Smith says, he’s not an urban cowboy, despite the 10-gallon hats and dusters he favors.

When family matters brought him back to Buffalo, Smith took the reins of Rigidized, the sheet-metal fabricator that his grandfather founded in 1940. The firm uses a patented process to roll three-dimensional textured patterns onto steel surfaces like elevator interiors, helicopter floors, even SEPTA doors.

“I wrote my final paper at Penn on the demise of the steel industry,” Smith says with a laugh, “and I ended up immersed in steel.”

Indeed, Bethlehem Steel and Lackawanna Iron and Steel once had large presences in Buffalo. But for more than a century now, those concrete silos have helped define the city.

When the Erie Canal opened in 1825 and eased the transport of Midwestern wheat to the Hudson River, Buffalo boomed. It began building grain elevators, which scooped grain from incoming ships and tossed it down into the cylindrical silos, where it was sorted for delivery throughout the East Coast and overseas. The first silo to be constructed by pouring concrete into slip forms was Buffalo’s American Elevator in 1906. Local designers also pioneered silo arrays, gifting Buffalo with an undulating, corrugated form that has proved iconic. During their heyday, more than 30 elevators lined the Buffalo riverfront. Today fewer than half survive, and only a handful are still used for their original purpose. (That waft of eau-de-Cheerios in the air comes from the Gold Medal flour that General Mills produces here.)

But increasingly, the empty ones are being repurposed. A beer garden has opened amidst the ruins of a grain elevator as part of Riverworks, a complex that offers silo-climbing, an indoor skating rink, a brewery, and a bar retrofitted into an existing grain silo. Elsewhere, another abandoned elevator plays host to a light show. Three miles south of downtown lies SolarCity, a gigantic solar-panel manufacturing operation recently acquired by Elon Musk C’97 W’97 that has become a linchpin of Governor Andrew Cuomo’s “Buffalo Billion” economic development initiative.

On weekends, kayakers zip around the waters of “Elevator Alley,” where six of the hulking concrete complexes cluster. It’s a striking sight for Smith.

“In the old days, we’d see a boat a summer,” he says. Silo City itself is constantly changing—this spring, it will unveil a new tapas bar in a rundown office on the property. “For the first time in 10 years, we’ll have running water,” Smith chuckles.

Still, he adds, he wants to take it slow … and easy. “I want to look around the site for opportunities, but without stepping too heavily. We want to keep growing, but most of all we want to help heal these old industrial grounds.”

—JoAnn Greco