A five-year conservation program is restoring Penn’s extensive—and long-neglected—collection of bronze outdoor sculptures to their former glory “to be seen, enjoyed, and inspire anew.”

By Carolyn R. Guss

“I have been the more particular

in this description of my journey that you may compare such unlikely beginnings

with the figure I have since made there.” So wrote Benjamin Franklin

to his son, words that appear at the base of a bronze monument on the

Penn campus that depicts the University’s Founder as a lad just starting

out, with his rucksack, wide-legged gait, and walking stick. He strides

ahead, clear-eyed and resolute, a young man leaving his boyhood behind.

It is as much a tribute to youth as to Franklin — and a fitting inspiration

to students just setting out on their own life paths. At least the Class

of 1904 thought so, when they dedicated the sculpture and its surrounding

plaza on the occasion of their 10th Reunion.

Unfortunately, the figure of Benjamin Franklin in

1723 “made there” by sculptor R. Tait McKenzie did not

age as gracefully as its real-life counterpart. Standing outside Weightman

Hall for 80-odd years, it was dirty and green — and quite crusty, albeit

in a different fashion than the man who inspired it. It needed a bath

— and some good old-fashioned TLC (something the pleasure-loving, flesh-and-blood

Franklin would have readily endorsed).

Recently, young Ben got his bath and more, thanks to

a donor from Harvard (of all places) and a five-year program at Penn to

clean and conserve the University’s bronze outdoor sculptures, which entered

its fourth year in July. Spearheaded by Jacqueline Jacovini, GFA’84,

associate curator of Penn’s art collection and herself a sculptor, the

project began tentatively in 1992 with an informal survey of sculptures

on campus conducted by Jacovini and interested volunteers, under the direction

of the Washington, D.C.-based Save Outdoor Sculpture! (SOS!), a national

organization jointly administered by the Smithsonian Institution and the

National Institute for Conservation of Cultural Property (now Heritage

Preservation). Following the survey, Jacovini talked with local experts

on bronze — Philadelphia is home to many, she notes — about the potential

for the project, and obtained recommendations on conservators. In 1994

the selected contractor, Norton Art Conservation, Inc., of Lafayette Hill,

Pa., formally reviewed 19 outdoor bronze sculptures and monuments on the

immediate Penn campus and, together with Jacovini, assessed the current

condition of and work needed for each.

A bust of Charles Lennig, a major benefactor of the University in the late 19th century, created in 1900 by John J. Boyle a year after the artist sculpted the stately seated Franklin in front of College Hall, served as a convincing test case. (This bust, which usually stands behind College Hall, has been temporarily removed during construction of the Perelman Quad.) Jacovini used the Lennig piece, conserved in 1995, to demonstrate to Penn administrators the significance of the project and the impact bronze conservation would have campus-wide. “It was truly before-and-after, night-and-day — and it was amazing,” she explains. “Here you had this powdery, chalky, greenish-white, ghoulish-looking bust that all of a sudden came to life. I had never noticed before how beautifully sculpted it was.” Others noticed too, such that the project got the go-ahead and a dedicated fund was set up within the University to provide for a five-year program of conservation and maintenance.

In the case of the youthful Franklin sculpture, Albert H. Gordon, an alumnus of Harvard University’s Class of 1923, was attending Penn’s Heptagonals in 1997 when he found the sculpture’s condition “atrocious,” and was appalled that the monument had fallen into such disrepair. Despite his having “never agreed with” Franklin or his philosophies, recalls Audrey B. Schnur, C’89, director of major gifts for athletics, Gordon decided to fund conservation and restoration of the monument and its surrounding plaza in honor of his friend, Gerald H. McGinley, W’52, a former Mungerman and long-time Penn supporter and winner of a 1998 Alumni Award of Merit.

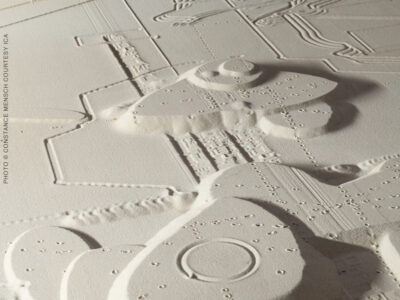

The process of conserving each sculpture evolves as a collaboration between the conservation team and the curator. Virginia Naudé, chief sculpture conservator for Norton Art Conservation, the firm she founded in 1987, begins by examining the work and drawing up a proposal detailing needs and costs that is then reviewed by Jacovini, and results in a formal contract. First on the list is a pressurized water and detergent washing, to remove surface grime, bird guano, and other superficial elements. Some sculptures receive a follow-up cleaning in which an air shower of walnut shells finely ground into a powder (a technique first devised to clean aircraft and fine machinery) is sprayed onto the bronze surface at 35 pounds pressure per square inch, a process that lifts superficial corrosion products (such as Lennig’s powdery white-green) and other chemical residues. Any specific concerns regarding the sculpture’s individual problems are also addressed, including removal of graffiti, any necessary structural repairs, and sometimes reinforcement of lead fillings in seams formed during the casting and fabrication processes. Finally, a protective coating of wax is applied, often by heating the bronze surface and applying the wax — which is absorbed by the metal, thus darkening the bronze. Alternatively, the substance can be applied to the cooled metal, which preserves the current color, as was the case with the imposing King Solomon, a 1963 work by Alexander Archipenko (gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey Loria), which did not require the intensity of cleaning and conservation as some of the older bronzes.

One of the few pieces that required what Naudé refers to as a restoration is the engaging Pan with Sundial, which resides in relative obscurity outside Van Pelt Library. Presented to the University in 1938 by Mrs. William Stansfield, “in loving memory” of her husband, C’02, the sundial’s gnomon (the raised piece that casts the shadow)was lost somewhere along the way, rendering it non-functional. Jacovini’s decision to have the gnomon, as an integral part of the sculpture, replaced resulted in a bit of research and, ultimately, some guesswork in the design detail, as old photographs of the piece depicted the gnomon from every angle.

To keep things interesting, the project’s span has overlaIpped the ongoing University construction. Two large sculptures had to be moved off-campus for cleaning and conservation, although each has since been restored to its original location on campus.

The majestic seated figure of Edgar Fahs Smith, provost of the University from 1911 to 1920, sits outside Smith Walk, near the Roy & Diana Vagelos Laboratories of the Institute for Science and Advanced Technology. This was also done by R. Tait McKenzie, a doctor of medicine as well as a sculptor, who was director of physical culture at the University for many years. It was sculpted in 1925 (10 years after McKenzie’s young Franklin) and donated by John C. Bell, C’1884. Smith is as dignified as young Franklin is ebullient. One can’t help noticing the feet of each man, prominent in both sculptures: Franklin striding, letting no grass grow; Smith rooted among his books and oak leaves, left brogue trampling a gargoyle of ignorance.

Nineteenth-century chemist John Harrison was vigorously immortalized a century after his death by sculptor Lawrence Tenney Stevens in a powerful standing figure donated by Harrison’s grandson, Thomas Skelton Harrison, in 1934. Located in a courtyard between 33rd and 34th Streets and Spruce Street and Locust Walk, the newly conserved Harrison would probably have delighted in the chemical process that cleaned each finger and curl.

The most challenging — and expensive — piece conserved to date, because of its size and many components, is the War Memorial, a commanding monument within a plaza that stands on Smith Walk at 33rd Street. A collaboration between sculptor Charles Rudy and architect Grant Simon, this tribute to Penn’s “sons who died in the service of their country, 1740-1950,” was presented to the University by the Hon. Walter H. Annenberg, W’31, Hon’66, in 1952. The monument is comprised of five oversize bronze figures (three male, two female) encircling a steel flag pole, a massive black granite base, and a surrounding limestone and brick wall — all of which needed attention. Enter the Class of 1943 which, in celebration of its 55th anniversary, has largely funded the memorial’s restoration in memory of classmate Frederick C. Murphy, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor after having been killed in the line of duty in Germany in 1945 [“Alumni Profiles,” Nov/Dec 1998].

Along with the requisite cleaning and waxing, the restoration process has included patching the stonework surrounding the piece, regilding the gold-leafed ball atop the flag pole, and addressing structural and other problems caused by the pole — which during the restoration process was discovered to be slightly off-center. Naudé explains that “at the bronze collar, the proximity of the bronze to the steel caused the steel to deteriorate faster, a process known as galvanic corrosion.” Conservation treatment included placing a zinc barrier on the steel pole to prevent further deterioration in the area of the bronze collar.

Jacovini emphasizes that along with the cleaning and

conservation of these works is the overarching issue of maintenance. “It’s

really unfortunate if you spend all the resources to conserve a piece

and then there’s no funding for — or interest in — maintaining it, because

in short order it will revert back to its previous condition.” Naudé

echoes the point that maintenance, such as was performed this spring on

the seated Franklin sculpted by Boyle (the piece was fully conserved in

1997), need not be labor-intensive but is “essential for preserving

these priceless collections.”

Frank G. Matero, chair of the graduate program in historic

preservation at Penn, who has served as a consultant to the bronze conservation

program, says that “These [sculptures] must be seen as a collection,

even though they happen to be outdoors.” He notes that art in outside

spaces “isn’t perceived in the same way, and tends to not receive

equal attention in terms of care that other types of artworks do.”

Although in some ways these sculptures are public pieces

of art because of the public’s accessibility to most of them, the issue

of care and maintenance rests with the University, Matero believes, a

sentiment echoed by Virginia Greene, G’68, senior conservator at

the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

She acknowledges that while “conservation and preservation can be

expensive,” it is “the responsibility of the University to do

as much as it can to preserve this artistic legacy.”

Naudé agrees. “The University of Pennsylvania purchased

and was given some of the most beautiful examples of sculpture from the

turn of the century to the mid-20th, and the bronze conservation project

has brought back the visual history embodied in these pieces to campus

life. The sculptors’ intent is again made clear, and these faces that

inspired so many are now there to be seen, enjoyed, and inspire anew.”

Jacovini joins Matero in acknowledging guidance and

assistance throughout the project from the National Park Service, as well

as the city of Philadelphia, which, as Matero sees it, has become a model

of management regarding outdoor-sculpture collections. In turn, Dennis

Montagna, director of the Park Service’s monument research and preservation

program in Philadelphia, lauds Penn for its endeavor, noting that “A

lot of universities haven’t undertaken this level of conservation and

care.”

With the project in its last two years and roughly 15

pieces cleaned and conserved, results are dramatically evident across

campus, causing some viewers to ask if sculptures have been replaced with

new castings or duplicate pieces, a situation that delights Jacovini.

“I hope that all of the work we’re doing is going to increase public

awareness — not just of these objects, but of what the objects stand

for,” she says. “These are things that have been significant

— whether to donors or to the Penn constituency. They commemorate important

people from the University’s history, so it’s wonderful for an educational

institution to promote these things by caring for them — because it’s

promoting values at the same time.”

Carolyn R. Guss, a former employee of the Smithsonian Institution and National Endowment for the Arts, is an advocate for the protection and preservation of public art.