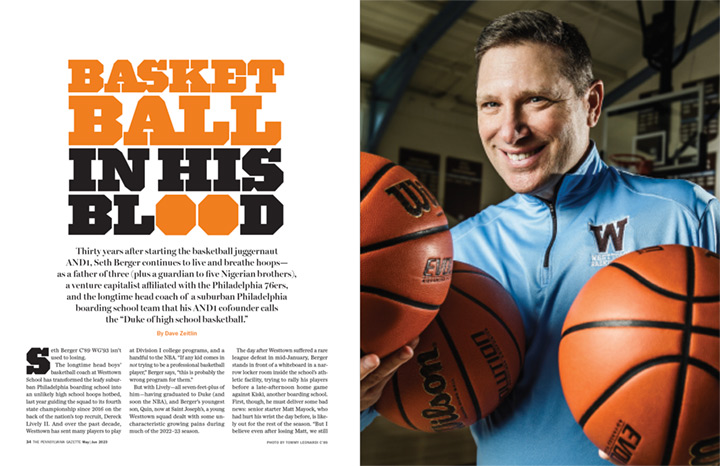

Thirty years after starting the basketball juggernaut AND1, Seth Berger C’89 WG’93 continues to live and breathe hoops—as a father of three (plus a guardian to five Nigerian brothers), a venture capitalist affiliated with the Philadelphia 76ers, and the longtime head coach of a suburban Philadelphia boarding school team that his AND1 cofounder calls the “Duke of high school basketball.”

By Dave Zeitlin | Photography by Tommy Leonardi C’89

Seth Berger C’89 WG’93 isn’t used to losing.

The longtime head boys’ basketball coach at Westtown School has transformed the leafy suburban Philadelphia boarding school into an unlikely high school hoops hotbed, last year guiding the squad to its fourth state championship since 2016 on the back of the nation’s top recruit, Dereck Lively II. And over the past decade, Westtown has sent many players to play at Division I college programs, and a handful to the NBA. “If any kid comes in not trying to be a professional basketball player,” Berger says, “this is probably the wrong program for them.”

But with Lively—all seven-feet-plus of him—having graduated to Duke (and soon the NBA), and Berger’s youngest son, Quin, also having moved on to the college game, a young Westtown squad dealt with some uncharacteristic growing pains during much of the 2022–23 season.

The day after Westtown suffered a rare league defeat in mid-January, Berger stands in front of a whiteboard in a narrow locker room inside the school’s athletic facility, trying to rally his players before a late-afternoon home game against Kiski, another boarding school. First, though, he must deliver some bad news: senior starter Matt Mayock, who had hurt his wrist the day before, is likely out for the rest of the season. “But I believe even after losing Matt, we still have the most talented team in the state,” the head coach says. “We don’t have the biggest, we don’t have the most veteran, but we do have the most talented.”

Heads pop up. Knees begin to bounce. All eyes are locked on Berger, who has been coaching at Westtown for 18 years, the last 16 as head coach, after selling AND1, the popular basketball footwear, apparel, and entertainment company that he cofounded 30 years ago, stemming from a Wharton graduate school project. As AND1’s CEO, Berger says he used to operate “very much like a coach, in terms of helping people figure out what they’re really good at and letting them do their thing.” So even though he describes himself as an introvert, he’s deployed that same strategy to inspire and motivate in pregame speeches that one former player described as “legendary.”

“Yesterday was a bump in the road,” the head coach continues. “As soon as we walk upstairs, let’s make it a little bump in the road and get back on track on the way to a state title.”

For the next two hours, Berger is on his feet—yelling, stomping, gesticulating, trying to will his team to victory. And this, apparently, is his Zen mode. “Seth will tell you he’s the calmest coach he’s been in years,” says his wife Christelle Williams Berger W’89, a Penn Athletics Hall of Famer for track and field, noting that during his early years at Westtown he lost his voice every game. “But if you watch a video and see him up and down the sidelines jumping, I’m like, I don’t know if you’ve tempered it enough.”

When Berger decided to shift from entrepreneurship to coaching, he “ordered so many DVDs, talked to so many coaches,” Christelle recalls, that it became all-consuming at home. “I’m like, You do realize you’re not Coach K and getting paid Coach K money with the amount of time you’re putting in?” she laughs. Berger, in fact, only collects $1,000 per year from Westtown (which he says the school makes him take for tax purposes) and donates more back into the program. The sale of AND1 gave Berger financial independence—and these days he runs a venture capital firm backed by Philadelphia 76ers ownership. He considers coaching a way to give back to the sport he loves. Over the last 12 years, Berger says his players have been offered almost $11 million in college scholarships. “I’m coaching entrepreneurs by day and by night I’m coaching high school basketball players,” says Berger, who in 2016 started as managing director of the Sixers Innovation Lab (set to be changed to Potential Capital LLC), where he proudly reports that 65 percent of the companies the fund invests in have founders of color, and 40 percent have founders who are women.

A key part of helping his players prepare for their futures is focusing on academics. About an hour before the game against Kiski, as players trickle into the locker room, the first thing he asks them is, “How was your exam today?” When one player confidently predicts he got a 95 percent and said the hardest part was finishing early and waiting for it to end, Berger laughs. “Can’t say I ever said that!” (Even with a couple of Penn degrees, he considers himself more hooper than scholar, joking that “when I walk into this room, the average IQ goes down.”) With other players, the affable coach also shares a few laughs—as well as tough moments of honesty. He apologizes to his point guard for putting him in a bad spot the day before by not calling a timeout in the final minute, and candidly tells another player that he played poorly, suggesting that “mentally exhausting” exams and a bus trip might have factored in.

As it turned out, the team’s skid would continue with a tough loss to Kiski. And the next month, as other injuries piled up, Berger’s young squad bowed out of the Friends League playoffs in the semifinals and lost in the first round of the Pennsylvania Independent Schools Athletic Association state playoffs. Westtown still finished with a winning record but endured one of the worst seasons in Berger’s tenure—a harsh comedown from winning a state title the year before. “I think earlier in my career I would have been miserable, on a scale of 9.5 out of 10,” Berger says. “I think this season was more balanced; therefore, I was only 8 out of 10 miserable.

“You know, I dedicated a ton of time to try to figure out what else we could be doing,” he continues. “Coaching, as much as anything I’ve done, is an incredibly humbling profession. My assistant told me this great thing. He said, ‘One day you’re winning a state final, then the next day you’re googling basketball plays on YouTube.’”

Berger lets out a hearty laugh. At 55, he’s still learning a sport that he’s been playing, teaching, and planning his life around for decades.

HARDWOOD LESSONS

Growing up in Manhattan, Berger got some early lessons in basketball—and life—on the outdoor courts of Central Park. “One of the best players I ever played with was a drug dealer named Frank,” he says. “And then you’d play with investment bankers and prep school kids. If you’re gonna play basketball in New York City, you have to be pretty comfortable quickly in any environment with anyone. I kind of feel like I grew up on the basketball court.”

As a 13-year-old playing with grown men, Berger’s main goal was “not to fuck up.” In time he developed into a “pretty good drive-and-dish point guard,” adept at putting his teammates in good spots. That’s what Steven Bussey C’89 noticed when the two began playing ball together at Horace Mann, a private prep school in the Bronx, where they quickly became best friends. “Seth and I played basketball every day,” Bussey recalls. “We played against a couple of teachers until eight or nine o’clock at night. We came in the morning before school to play; we played on the weekends; we literally managed the girls’ softball team so that we could play in the gym.”

As high school juniors on Horace Mann’s varsity basketball squad, Bussey was the star while Berger was still trying to carve out his role. During one practice that season, Berger recalls head coach Chet Slaybaugh telling the players that someone needed to step up and emerge as a leader. The next day, Berger, who had been a quiet kid to that point, requested a meeting with Slaybaugh. “I said, ‘Coach, I heard what you said yesterday. I know I’m not the best player or captain, but I think I can be the leader of the team,’” Berger recalls. “I’ll never forget it. He said, ‘Berger, I was talking to you.’” It was a pivotal moment in his life. “I never would have been able to be a CEO of a company had I not had that conversation with my high school coach.”

As the team’s senior leader in 1985, Berger helped Horace Mann win a league championship. But a school policy prevented the team from competing in the state playoffs. Jay Coen Gilbert, Berger’s Horace Mann teammate, best friend, and future AND1 cofounder and partner, called it a “painful moment”—drawing a contrast to Westtown, which he calls the “Duke of high school basketball” for its combination of academic rigor with the chance to compete for titles every year. “That’s a gift that he didn’t have,” Coen Gilbert says of Berger. “He’s making sure those kids are seen as whole people, just like he was by Coach Slaybaugh, but he’s also going to give them a chance to be their best and play in the state tournament that he didn’t get to play in.”

As for Berger’s hoops skills in those days, Coen Gilbert calls his friend “a quintessential point guard and floor general”—which he believes may have been another predictor of Berger’s future. “You’re not gonna win the game by yourself. You’ve got to get the ball to the right people at the right time in the right position for them to be their best. I think that’s what a good point guard is, and I think that’s what Seth has brought to basically every role he’s ever had.” (Coen Gilbert also got an early taste of Berger’s competitive streak in seventh grade, when Berger asked Coen Gilbert if he wanted to box. “I was like, ‘OK, whatever, sure,’” Coen Gilbert recalls. “And he promptly punched me right in the solar plexus as hard as he could. I couldn’t breathe, threw off my gloves, and was like, ‘Dude, what the fuck?’”)

During his junior year, Berger attended a Penn basketball game and came away “certain I was good enough to be their starting point guard,” he recalls, before quickly adding, “I was massively deluded.” Though he wasn’t recruited by the Quakers, he got into Penn and decided to come. The summer before arriving on campus, he called Penn head coach Craig Littlepage W’73 to see if he could practice with the Quakers—which he did for about three weeks, until Littlepage left for Rutgers, replaced by Tom Schneider. A Schneider assistant quickly told Berger he wouldn’t be needed, effectively ending his college basketball dreams—but not his college sports dreams. That night, he says, a member of Penn’s sprint (then called lightweight) football team asked Berger if he’d be interested in joining them. Berger, who had played football at Horace Mann in addition to basketball, figured he’d give it a shot. He ended up being a program stalwart for head coach Bill Wagner, who coached Penn sprint football for 50 years before recently retiring at the age of 80 [“The Unlikely Legend,” Nov|Dec 2019]. “I loved it,” Berger says. “I loved playing for Wags. I loved my teammates.”

An excellent wide receiver, Berger also learned a valuable lesson in humility from Wagner. After a loss to Princeton, he recalls storming into the coach’s office to ask why he wasn’t getting the ball thrown to him more. “And he goes, ‘Look Berger, if you don’t like the way this team is being run, you can quit. If you want us to pass you the ball, start blocking.’” Berger’s reply would become his three favorite words: “Got it, Coach.”

At one point, Berger thought about transferring to a Division III school to play basketball, but a conversation with his father changed his mind. “My dad said, ‘Listen, you might not realize this but you’re not going to be a professional athlete. You might want to stay at Penn to figure out what you’re supposed to be,’” Berger recalls. “That’s when two things happened: I got into student politics and decided my junior year to play JV basketball.” Joining Penn’s junior varsity team allowed Berger to again be teammates with Bussey, play games inside the vaunted Palestra, and find a valuable mentor in the team’s coach, Kevin Touhey. Years later, when Touhey became a motivational speaker, he visited Westtown to advise Berger on his coaching style. According to Berger’s recollection, his old coach told him, “You keep looking at your assistants about what to do. You’re not trusting your feel. What made you a really good point guard is you had really good feel.” (The next year, in 2016, Westtown won its first state championship. The night of the title game, Touhey passed away from lung cancer.)

Berger only played one season of JV ball for Touhey because of an injury he suffered in the last sprint football game as a senior, but he got involved in an organization called Students for Racial Equality. There he ran into Christelle Williams, an African American track star he’d seen running around the track at Franklin Field. “She wouldn’t pay attention to me,” Berger says. “I always saw her.” It wasn’t until they reconnected at their five-year reunion in 1994 that the two went out on a date. They went to see Four Weddings and a Funeral even though Berger had already seen the movie three times, but only after a meeting-place snafu torpedoed their dinner plans. Trying to make amends at their next date, they returned to the same mall—and ended up having a five-hour dinner at Houlihan’s. “I knew right then this was the woman I’d marry,” Berger says. Now married almost 27 years, “my wife is literally my greatest teammate.”

BUILDING A BUSINESS (NO SUITS REQUIRED)

After graduating from Penn in 1989, Berger figured he’d get into politics or follow his parents into a legal career. He moved to Washington, DC, to serve as legislative director for Congressman Harold Ford Sr. But while it was “a great learning experience,” he was “too much of an introvert” for the political functions and parties, he says. Deciding to get another degree, he preferred two years of business school to three years of law school. So back to Penn it was, this time to attend Wharton.

Berger’s “biggest stroke of luck” as a Wharton graduate student came in the second semester of his first year. That’s when he took an entrepreneurship course with professor Myles Bass. Over the span of 10 weeks, Bass brought in different entrepreneurs to discuss their start-up journeys. “And I was like, Ah, this is what I’m supposed to do,’” Berger says. In addition to appreciating the freedom and flexibility that starting your own company could bring, he also liked how “as an entrepreneur, you basically have to use all parts of your brain: sales, marketing, finance, relationships—you name it,” he says. “The other thing about being an entrepreneur is it’s constantly a game. You are winning or losing every single day.”

Yet with student loans piling up, Berger initially figured he’d follow the more conventional—and lucrative—path into investment banking. The summer after his first year at Wharton, he interned at an investment bank—and hated it. “I put on 15 pounds. I played ball only one night. And I was bad as an investment banker,” he says, adding that the worst part may have been the bank’s requirement that men wear suits. So, for much of that summer, Berger worked on a business plan that stemmed from a project he had done for Bass’s class: a basketball retail store called “The Hoop.” That business evolved into a database of recreational basketball players that could be marketed to companies like Nike and Foot Locker, a precursor to AND1 (whose name echoes the triumphant shout of a hoops player making a shot while getting fouled). He worked on that plan throughout his second year at Wharton, eventually ditching the investment banking path (during a round of job interviews, no less) to go all in on AND1.

Berger had met a Wharton undergraduate named Tom Austin W’93 GEd’08 on the basketball courts at Gimbel Gym (now the Pottruck Center) and was impressed by both his game and his smarts. “To this day, he’s the only person I’ve ever met that is amazing at left and right brain stuff,” says Berger, who convinced Austin to join him on his basketball start-up journey. Austin would soon become the company’s creative engine. Coen Gilbert, meanwhile, decided to hop aboard over drinks with Berger at Ortlieb’s, a jazz club in Philly’s Northern Liberties neighborhood. “I couldn’t stop asking the waiter for pens and paper and napkins to write ideas down that were popping into my head all through the first and second set,” Coen Gilbert recalls. “By the end of the weekend, Seth and I looked at each other like, are you thinking what I’m thinking? That Monday I gave notice at my job and told them I’m leaving to pursue an entrepreneurial gig with my best friend and moving to Philly.”

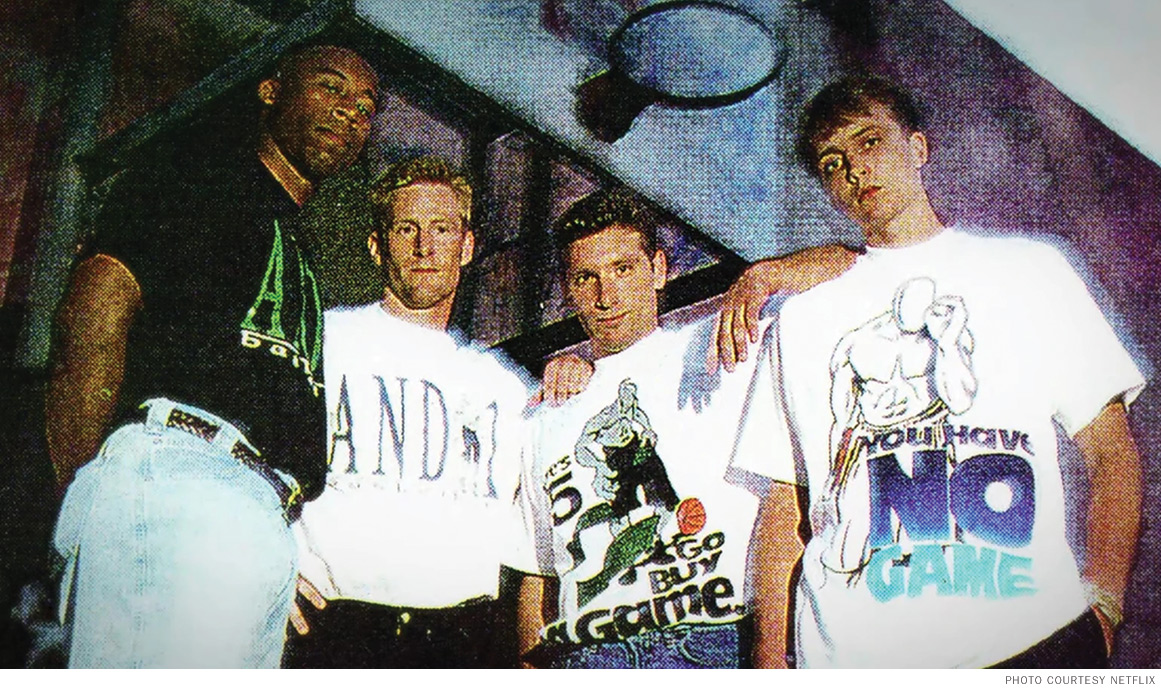

Another napkin scribbling session would prove even more formative. The summer they started the company, in 1993, Berger, Austin, and Coen Gilbert drove to Chicago for a sports trade show, where they pitched their database business. The response was not good, as Berger recalls. But one part of it held promise: giving T-shirts to the players who signed up. At a deep-dish pizza place that weekend, Berger, Austin, and Coen Gilbert started jotting down slogans for T-shirts that basketball players might want to wear while playing ball. “We thought we could make more creative gear that would speak to a basketball player, to allow a basketball player to identify as a ballplayer, more than other brands,” Berger says. “It didn’t matter that I didn’t play a minute of Division I or ever make a penny playing the game—I thought of myself as a basketball player. And there are so many other people, men and women, who look in the mirror and see a basketball player. So what AND1 did was allow people to say, ‘I’m a ballplayer. That is how I see myself.’” It dawned on Berger then, as they “literally threw our pitch decks away,” that two Wharton alums and a Stanford grad were going into the T-shirt business.

Back in Philly, they continued to come up with slogans—which were more like disses, the kind of trash talk they used to hear playing pickup games in the playground or gym. Every Monday morning, they were supposed to come into the office (which in the company’s early days was in Berger’s sprint football teammate Nate Scott C’89’s house outside of Philly) with 10 new ones. Of the three cofounders—and soon three other partners: Ray Moseley WG’92, Bart Houlahan, and Guy Harkless—Austin’s would invariably be the best, including Berger’s favorite: “I’m the Bus Driver. I Take Everyone to School.” As for Berger’s, well … “Seth was absolutely terrible at slogans,” Coen Gilbert says, as only a best friend could. “He is the most unoriginal, not funny, not creative human being.” His primary role driving the business forward, Coen Gilbert adds, was being “a great strategic thinker who’s spending all of his time trying to think two, three steps ahead,” like the point guard and poker player that he is. “Seth’s got a photographic memory and a nonstop analytical brain.” (Berger doesn’t deny he’s more strategic than creative but remains happy with at least one of his slogans: “Grab a Straw Because You Suck.”)

As any teenager from the ’90s could tell you, it became commonplace to see AND1 shirts with a faceless, musclebound player alongside slogans like “Call Me the Surgeon. I Just Took Your Heart” and “Pass. Save Yourself the Embarrassment.” As shirt sales expanded, reaching 1,500 Foot Locker stores by the company’s second year, the brand began to “have meaning that we could not have anticipated,” says Berger, recalling a college basketball player at St. Bonaventure who had the AND1 logo tattooed on his biceps.

The company quickly expanded to sell more apparel and basketball sneakers. Sales skyrocketed. Big-time NBA players were signed to endorsement deals. Vince Carter wore AND1’s signature Tai Chi sneakers during a memorable performance in the 2000 NBA Slam Dunk Contest.

Where AND1 really made its mark, however, was not in NBA arenas but famed playground courts like Harlem’s Rucker Park. The company’s aggressive, in-your-face marketing tactics meshed well with the inner-city streetball scene, a less formal hoops setting where showcasing fancy dribbling moves, often at the expense of a befuddled defender, was what wowed spectators crowding the park’s edges. Capitalizing on Michael Jordan’s retirement and the 1998–99 NBA lockout, AND1 blitzed the basketball world with mixtapes featuring playground players pulling off dazzling stunts. Riding the mixtapes’ success, AND1 began touring the country every summer to create more content and sign new streetballers to endorsement deals. Players known as “Skip 2 My Lou,” “The Professor,” and “Hot Sauce” became quasi-celebrities as they toured internationally, had their games televised on ESPN, and even sold out NBA venues.

Without much business experience, Berger and his team had managed to turn what began as a Wharton project into a company that hit more than $250 million in revenue in 2001 while capturing the hoops zeitgeist of that era.

And his company continued to thrive … for a while.

WESTTOWN AND FAMILY

Last August, Netflix released the documentary Untold: The Rise and Fall of AND1. Most of the film was dedicated to the company’s rise: electric mixtape tours, popular sneakers, gracing the cover of Sports Illustrated, a growing staff, bigger headquarters in Paoli, Pennsylvania.

But it also raised questions about the way the company’s founders had built wealth off (mostly Black) streetball players before cashing out and selling the company in 2005—which Coen Gilbert and Berger fiercely dispute. “I had an amazing 12 years with people who were my best friends or who’d become my best friends,” says Berger, rebutting the film’s characterizations by pointing out that two of the original six partners were Black and that the streetball players were given bonuses when the company was sold. “We truly had this amazing environment where I got to love the people that I worked with every day.”

Because of those relationships, selling the company was bittersweet—but not the sudden, unexpected jolt that the filmmakers made it out to be. Berger says they had already sold a third of the company to a venture capital firm in 1999 and plotted an exit strategy when Nike, already top dog in basketball sneakers, “effectively decided it’s time to squash AND1” with a well-produced freestyle basketball commercial in 2001 featuring NBA players pulling off fancy streetball moves. “Once I saw that commercial, I thought, Oh, we can’t win,” Berger says. “Competing to be number two wasn’t really fun.” For the next few years, as AND1’s sales began to slide, they waited for the right opportunity to exit, eventually selling to American Sporting Goods in May 2005. (AND1 has since been sold multiple times but the brand has endured, this year celebrating its 30th anniversary.)

At the time, Berger didn’t know what he’d do next, other than spending quality time with his three young children. The opportunity at Westtown came about after Coen Gilbert, who sent his son there, told Berger to look at the West Chester, Pennsylvania, school, which was located only about 15 minutes from Berger’s home. He was immediately impressed by the diversity of the student body and felt good about sending his boys there. After their oldest son, Cole, enrolled, Berger went to some basketball games and asked the head coach, Joe Paris, if he needed a volunteer assistant. He was offered the job, served two years as an assistant, and when Paris resigned was hired as the head coach, intent on building a program at a school not especially known for athletics.

Berger running a new kind of basketball start-up didn’t surprise anyone who knew him. “It was either coach or make a late run as point guard of the Knicks,” Coen Gilbert quips. What did come as a surprise is how basketball would change the makeup of his family. Early in his coaching tenure, Berger got a letter from twins in Nigeria who wanted to play basketball and pursue their education in the US. Impressed by their intelligence and personalities (along with their hustle and raw potential on the court), “I said to my athletic director, ‘These are the kinds of kids I want to build my program around,’” Berger recalls. Receiving enough financial aid to make their American boarding school dream a reality, Longji and Nanribet (Nan) Yiljep were soon at Westtown, with the Bergers serving as their host family. “And we pretty quickly figured out they were amazing role models for our kids as young men of color,” Berger says. Westtown’s host family program is designed to give international students and other boarders a place to perhaps celebrate a birthday or have lunch. But with the Yiljeps, it always felt like something more. And when the twins’ father, an agricultural engineering professor in Nigeria, unexpectedly died, the Bergers offered to become their guardians. Soon, their three younger brothers, Yilret, Dakpe, and Junior, followed the twins to Westtown—and the Berger clan of five became the Berger–Yiljep clan of 10. “What’s interesting is there was never a plan,” Christelle says. “People decide to be foster parents, they decide to be adoptive parents, but there wasn’t a conscious decision we made.” But, she adds, “they literally just flowed right into our family.”

What was it like with as many as eight boys under one roof? Lots of video games, lots of eating, lots of basketball games on the court outside the Bergers’ home. “Competitiveness just permeates through everything we do,” Nan says. “But as much as we’re competitive with each other as brothers, all eight of us support each other and our individual pushes.”

With Berger, the banter is incessant, especially about the “charity win” Longji and Nan claim they long ago gifted Berger and former Westtown principal Eric Mayer in a 2-on-2 game because “we respect our elders,” Longji laughs. But they’ll never forget the compassion and selflessness Berger displayed after their father died. “What showed us his humanity,” Nan says, “was the fact that he had never met our dad before face to face, but the way he delivered the message to us, he was crying as if it was his brother who passed away. He embraced us, he covered all of the expenses for us to go home. … Seth pretty much became our dad at that moment.”

Berger continued to support the Yiljeps both emotionally and financially, taking them on college visits and continuing to cover the cost of whatever they needed: books, basketball sneakers, flights home for the holidays. When Longji thought about quitting the team at Brown because of an injury, Berger “was on the next flight just to talk to the coaching staff and the trainers,” Longji recalls. Nan, who played college ball at Skidmore College, was stunned to see Berger in the crowd as he warmed up for a playoff game during his senior year.

Adjusting to American life wasn’t always easy for the Yiljeps—particularly the food (though that part is much better now that their mom has moved to the area and often cooks authentic Nigerian lunches for them.) But today the brothers have carved out quality lives for themselves in the US, with Nan working at Westtown as a digital marketing and social media analyst, a dorm parent, and an assistant coach on Berger’s staff. Longji is a senior analyst for a shipping company in Connecticut, but works from home, living with Nan in a Westtown dorm building.

“Just the human being that he is and his caring for other people and his character sets him apart from anybody that I know,” says Berger’s friend Bussey. “His willingness to confront prejudice and racism as a white man married to a Black woman, with three Black kids of his own and five adopted Black kids, those are the kinds of things you don’t see or hear with him—but it makes him who he is. He’s a Jewish kid from the Upper East side, I’m a Black kid from Harlem and Washington Heights, and we became best friends, experiencing everything together from sixth grade on.”

With all their children and all the Yiljeps having moved on to college and adulthood, the Bergers are entering a new phase as empty nesters, having recently moved to a smaller home. But he doesn’t plan on leaving Westtown any time soon. The end of last season may have seemed like a natural conclusion after Quin graduated with a state championship. In what Berger calls a “poetic” end to the season, Quin made two free throws to ice the title game and then “runs to me and hugs me and he’s bawling his eyes out,” Berger says of his youngest son, who played the entire season with a torn ligament in his left thumb. “Now you realize how much pressure he felt.” (Berger’s middle son, TJ, who’s now at Lafayette, similarly felt a lot of pressure playing for his dad en route to two state titles.) But now Berger is excited to simply be a father to all his boys without the extra burden of also being their coach, while helping other high schoolers get to college and win championships along the way. “It’s funny,” Berger says. “Until my mid-40s, I looked in the mirror and saw basketball player. Now I see basketball coach.”

Although losing doesn’t crush him quite as much as it used to, the sport still means everything to him. Before a game this past season, he recalls sitting in the locker room for five minutes by himself listening to Sade’s “Love Is Stronger than Pride” with his eyes closed and the lights off. “If I stop getting nervous, then it’s time for me to stop coaching,” he says. “If I stop wanting to improve, then it’s time for me to stop coaching.” But he doesn’t anticipate that happening until maybe he’s as old as his former sprint football coach was when he stepped away.

“Somewhere around 80, I’ll retire,” Berger says. Then when he dies, he adds with a smile, he’ll want his ashes scattered in the lake at Westtown, where a second career turned into a true calling.