An 81-year old traveler tackles a 200-mile bike ride in southern Italy.

BY JERRY LEVIN

Cut by a deep ravine, Matera occupies a series of steep hillsides riddled with caves that were continually inhabited for 10 millennia until the 1950s. The north rim of the canyon is now empty of people, but the south side remains vital, its ancient homes and businesses pushing right up against the gorge. I’d been coaxed here, to the arch of Italy’s boot heel, by a catalog of cycling tours that landed in my mailbox some time after my 80th birthday.

As far as my wife, Sara, was concerned, our previous cycling excursion—in the Dolomites—had been our last. But evidently the beginning of my ninth decade had not shaken the addiction to rugged travel that marked my previous eight. For all my life I’ve been driven by a desire to “light out for the territories”—be it sleeping in a jungle hammock for a summer on Hawaii’s Mount Tantalus, or kayaking Alaska’s Glacier Bay among the whales and grizzlies. And old habits die hard. At 67, I hiked for days in near-blizzard conditions to look down on the Everest base camp from the 18,300-foot ridge of Kala Patthar. The next year I climbed Mount Kilimanjaro. At 71, I plunged into a crevasse on Mount Denali [“Essays,” Jan|Feb 2009], and I finished the 735-mile New England section of the Appalachian Trail at 75.

VBT’s Puglia itinerary lured me in with the seeming promise of flat riding along coastal routes. As a prelude I’d come to Matera, whose gorge, with its one-person-wide suspension bridge and switched-back trail that passed innumerable caves, reminded me of trekking in Bhutan. I stayed in a cave dwelling, in a bed occupying the space where a donkey once would have slumbered. It sent my mind reeling back to another stone grotto, in Cappadocia, where Sara and I had slept many years before. She would have loved Matera’s spare and windswept beauty, and already I missed her intensely. Several attempts at a telephone connection failed, spurring a conflicted set of emotions: loneliness, guilt, and exhilaration. So to fully enjoy Matera was emotionally challenging.

And physically challenging as well. Everywhere there were steps to ascend—or angled slopes covered with loose rocks. And every ascent foretold of an eventual descent, which strained my joints even more. My arthritic left ankle was simply not to be trusted in this terrain, so I lined one climbing boot with the rigid tube of my Arizona brace, and broke out a walking stick fit for a Methuselah like me. And lo and behold, I could navigate this amazing town, albeit not too rapidly. Matera’s cave dwellings had been dug out of soft limestone and were not hermitages but organic communities connected by courtyards where a rich social life once thrived. When the Italian government forced the inhabitants to relocate to modern houses, many reportedly experienced a profound sense of loss that could not be mitigated by the conveniences of modernity. I would have felt the same way.

Now that I could walk with a minimum of discomfort, I loved the cave dwellings, the underground churches, the faded frescoes, and the sense of life’s continual unfolding in the natural world. But no sooner had Matera cast its spell upon me than it was time to move on, to actually start biking.

Now one month short of 81, I would find out if my experiment in anti-entropy could slow or reverse my progressive creak-a-ti-zation: not only that bum ankle but a bothersome left shoulder with a restricted range of motion, an intermittently sore right knee, bouts of lower back pain every morning, and an awareness that strenuous exercise—e.g., biking up a long hill—left me breathing hard and prey to a deep, radiating pain from my right thigh. I didn’t need a well-greased bike chain so much as I needed the Tin Man’s oiling can. Would I really be able to cycle 200 miles over the next six days?

Our starting point was Masse Torre Maizza, an enclosure originally erected by Puglian farmers who built walls around their land, encompassing a well, livestock, stable, church, and home. These masserie had been built to repel Adriatic pirates and buccaneers in the 15th century, and ours, like many others, had been converted into a resort. Its vantage over the eastern Mediterranean was a perfect backdrop for reading The Odyssey as translated by Penn’s own Emily Wilson, the first woman to render the epic in English [“An Odyssey for Our Time,” Mar|Apr 2018]. Since Greek is Greek to me, I have no idea how closely Wilson’s text conveys Homer’s original, but her translation sparkled with swiftness and bracing directness.

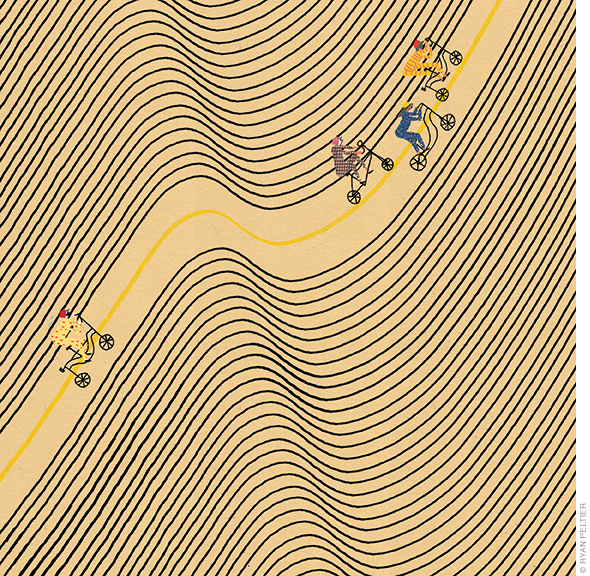

Overlooking a magnificent landscape trailing down to the seashore, we saddled up for a warm-up ride: a 10-mile round trip to a Roman ruin. Twenty riders set out at noon. I brought up the rear—but made it there and back without dragging the group down.

The next day we got serious: 35 miles to the ancient seaport of Monopoli. The ride to the coast featured a few challenging ascents as we passed through groves of 800-year-old olive trees, but nothing I couldn’t do. Then we turned to pedal northward along the Adriatic, confronting both a serene and undeveloped beauty and the unbelievable winds that had apparently driven mass settlement away. For 15 miles, we fought a headwind as indomitable as the palm of a Cyclops pressed against my forehead. The aching in my thighs only faded when overtaken by stinging pain, but I pushed on, pressing through the charming fishing village of Savelletri toward Monopoli. Soon shortness of breath was competing with my screaming quadriceps for my attention, but I reached the finish line, albeit by far the slowest of our caravan.

Monopoli proved to be a gem, with its battlements, fort, ancient harbor, crystal-clear water, and a superlative gelato to restore us for the return trip. That route went inland, and so lacked a tailwind, but after biking into the near-gale, even the one long climb seemed a piece of cake—sort of. At the end I hopped in a shuttle van to the beach. The Adriatic was a delight—translucent, warm, just wavy enough to be fun, and tinged with a sense of the exotic when I realized that I was looking out towards Albania.

I was a happy camper. After mastering the wind and hills, most of my anxiety about finishing the trip drained away and I was looking forward to the next challenge.

In the morning, we shuttled south to another part of Puglia, where the Apennines petered out into what would theoretically be flat territory. Yet it turned out that Puglia’s reputation for flatness is considerably exaggerated, even in realms where the mountains have receded from view. Tracing the undulations of cliffs overlooking the sea, our ride was beautiful but not easy. After six hours, though, a long descent delivered us to Otranto, where, changing behind our towels, we had another swim in the Adriatic. Otranto boasts a famous cathedral where the bones of 500 martyrs who refused to convert to Islam after a Turkish conquest are preserved. The cathedral is renowned for a sprawling 12th-century floor mosaic depicting the Tree of Life—but this, my fellow riders reported, was largely covered by chairs. Walking at the same snail’s pace that had ensured my chronic lateness to every destination, I didn’t even attempt to reach the cathedral.

Now came the moment of truth. Should I attempt the steep, mile-long rise from the seafront to the cliff top—or should I ride in the van? I chose the latter, having reached some sort of equilibrium between gratitude for the capacities I retained (after all, most people my age are dead) and acceptance of my age-imposed limitations. I consider that moment the psychological-emotional high point of the trip. Later I would occasionally kick myself for not trying, but mostly I was at peace with my decision. I had more trouble accepting my slow pace throughout the trip—always being last to arrive. Since one of our terrific guides was always charged with cycling in the rear, I often felt baby-sat and guilty over slowing him down. On the other hand, my feelings of inadequacy were mitigated by the one teenager on the trip, who was sufficiently awed by “great-grandpa’s” stamina that he requested a picture with me.

Yet we were not done. The next day presented still another challenge, perhaps not as daunting as the headwind but problematic enough. Heat! Under a punishing sun, several times I experienced heat-induced nausea and light-headedness that was definitely on the scary side. I got back to the masseria seriously dehydrated, for which I cured myself by chugging two liters of sparkling water on my way into the pool.

Counterpoised against my fear of sunstroke was the transcendent beauty of the southern Puglia coast, with its sculpted sea cliffs and grottoes suffused with intense, multi-hued light that reflected off sea, rock, and sand. Riveted by my surroundings, and absorbed in the ecstatic pleasure of the physicality of my struggle to reach the top of the cliffs in the heat, I mused about the meaning of it all. Here were all the elements that had driven my many adventures: rapture over the wonders of nature; the sense of well-being emanating from a body stretched to its limits; the concomitant overcoming of self as I pushed through fear and self-doubt; the sharing of meaningful experience with others; a spiteful satisfaction in imagining the kids who had seldom chosen the non-athletic Jerry for their teams now confined by beer-bellies to their recliners; the thrill of discovering the hitherto unknown; the just plain fun; and underneath it all, the reassurance of telling the soon-to-be encroaching eternal darkness “not yet.”

There is a paradox involved in intense striving for what often seems an unobtainable goal: it is at once total absorption in the self as well as transcendence of that self. And that dynamic tension is what I sought and still seek in adventure travel.

On the final day as I approached the finish for the last time, I felt a conflicting mixture of pride, dread of that pride crossing over into hubris, and fear of alerting the “evil eye.” Then as I pushed through the last hundred yards, joy broke through.

The next morning I found myself in Lecce. Here the local stone—soft, easily carved, and pinkish-white—had given rise to a baroque city whose spectacles made me perfectly happy to assume the bearing of an ordinary tourist. In its Duomo, I stood in brilliant sunlight dyed innumerable colors by some of the most beautiful stained-glass windows I’ve ever seen. Knowing how much Sara would have loved Lecce, I regretted not having pressured her to come, but fortunately I wouldn’t have to miss her too much longer. I was on my way home.

Now that I’ve retired from long-distance cycling, I don’t understand how the VBT catalog keeps showing up on my bedside table. Perhaps, like Ulysses, I’m fated to leave Ithaca once again.

Jerry Levin CGS’61 continues to write and explore as he practices psychotherapy in Manhattan and Long Island.

Jerry

I’m a fellow hiking Penn alum. Recently retired, I’m interested in hiking a section of the AT. (I’ve day or overnight hiked parts of the NH and ME AT over the years.). I’d love to hear about your section hike, including the pre- and post-hike arrangements.

If you have time, please let me know.

Joel Lerner

[email protected]