Design alumni Stephen Kieran and James Timberlake, the architects for the new Melvin J. and Claire Levine Hall on Penn’s campus, are on a mission to “refabricate” their profession.

By John Prendergast | Portrait by Greg Benson | All other photos courtesy of KieranTimberlake Associates LLP

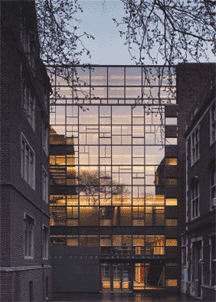

The transparent glass façade of the new Levine Hall makes a striking impression on the viewer, but the very first thought that comes to mind on seeing the building is: “How did they fit that there?”

The 48,000-square-foot, six-story home for the Department of Computer and Information Science, dedicated last April, sits on space formerly occupied by a service and parking zone tucked in among the School of Engineering’s Towne Building and Graduate Research Wing (GRW) and the English Department’s Bennett Hall. Named for Melvin J. Levine W’46 and his wife Claire, who donated $5 million toward the $15.5 million pricetag, Levine Hall physically and symbolically links the engineering buildings, and also creates a new campus vista by opening Chancellor Walk, previously used for parking, as the main entrance from 34th Street and landscaping the surrounding area. A second entrance was created on the Walnut Street side, where Levine joins with GRW.

The building features a double-height entrance lobby and a 150-seat auditorium, department and faculty offices, and lab and meeting space. The floor heights are 14 feet, which, along with some modest ramping, made it possible to link the differing floorplates of the three buildings. The project also included construction of a “cyber-lounge” in the former garage of the Towne Building, and creation of a new courtyard between Levine and the new bioengineering building, Skirkanich Hall, to be constructed on the 33rd Street side.

Levine Hall is the first building on campus to be designed by Kieran-Timberlake Associates LLP, the Phila-delphia-based architecture firm headed by Stephen Kieran GAr’76 and James Timberlake GAr’77, who also teach a final-semester design laboratory for master’s students in architecture in the School of Design. In its emphasis on knitting together disparate elements, its mixing of materials and textures, and its use of innovative building technology —the glass curtain-wall is exceptionally energy-efficient and was pre-assembled off-site for ease of construction—Levine Hall is representative of an architectural practice in which, as Kieran puts it, “we are as much mechanics as conceptual thinkers, or even more so.”

The area of campus in which Levine is located is a designated historic district, notes Timberlake, requiring design review by both the Philadelphia and state historic preservation commissions as well as Penn officials. The Towne Building dates from 1906 and GRW from 1967; Bennett Hall was built in 1925, the Moore School building, also nearby, was constructed in 1912 and altered in 1926. (Pender Labs, another 1960s-era structure, has been demolished for Skirkanich Hall).

Faced with such a varied building context, the best way for a new structure to fit is often to “refuse the choice” of imitating one style or another, “but do something that seams the existing pieces together,” says Kieran. “We very much think that Levine Hall does that.”

For example, at the corner where Levine and Towne meet, masonry blocks alternate with the glass windows in a zipper-like pattern to “join the new Levine building back into Towne without imitating it,” he says. “Then the glass wall slides back toward GRW, which is itself a glass building.”

Kieran and Timberlake praise Penn’s administration, and especially Engineering Dean Eduardo Glandt GCh’75 Gr’77, for a willingness to “press the envelope” in terms of the building’s design. The dean, says Timberlake, “didn’t express a desire for a glass building, but he did express the desire to have people understand what engineering was in the 21st century and to be able to understand that from without as well as from within” the building—which was also in keeping with the University’s general emphasis on turning its “face” back toward the community, rather than looking inward.

The need for openness meant that the glass wall had to be as transparent as possible, and not just a “shiny brick building,” Timberlake adds. But that goal seemed at odds with another critical concern—controlling energy costs efficiently. The conventional way for managing heat and light in glass buildings in the United States is to use tinted or reflective glass, which Kieran compares to “having a conversation with somebody who’s wearing sunglasses.”

To meet both goals, the designers turned to a ventilated curtain-wall system that had been used in about 40 buildings in Europe, but never before in the U.S. “This is a really good energy-management system for the building. It uses energy responsibly, and is extremely comfortable at 100 degrees or 10 degrees,” says Kieran. Though more expensive initially, it should save money over time in energy costs.

The system consists of a double-glazed glass unit on the exterior and an interior single-glazed glass unit in an aluminum frame, with air continuously ventilated through the cavity between them to maintain temperature. Electronically controlled blinds also hang within the cavity. The units arrived pre-tested and pre-assembled, and were basically hoisted up and “snapped” onto the building frame by a team of a half-dozen workers.

School of Design Dean Gary Hack praises Levine Hall on both technological and aesthetic grounds. “It restores the idea that we can do things which are at the cutting edge and which are exploring new technologies in our buildings,” he says. The curtain-wall system is “a really innovative way of handling the exterior of a building.” Hack calls it “very nice and very sophisticated building” that is also “extraordinarily important in the way that it connects all the pieces of the engineering campus together.”

The landscape architect Sir Peter Shepheard was dean of the Graduate School of Fine Arts when Steve Kieran and James Timberlake were students in the architecture program in the mid-1970s. Timberlake recalls him attending student juries, where he would sit and “draw these beautiful renderings of fowl—mallard ducks. There would be groups of students watching the jury, but then there would be a whole pile of students right behind Peter watching him illustrate this duck.”

He cites Shepheard as one source of KieranTimberlake’s interest in landscape architecture, but names as principal mentors Dr. Peter McCleary, then chair of the department—“an influence from the standpoint of his background as a structural engineer teaching in the architecture department”—and the late Steve Izenour GAr’65. Izenour taught both partners and also introduced them to Robert Venturi Hon’80 and Denise Scott Brown GCP’60 GAr’65 Hon’94, in whose firm he was an associate (and with whom he co-authored the seminal Learning From Las Vegas in 1972).

Kieran and Timberlake had crossed paths at Penn, but it was while working at Venturi Rauch and Scott Brown, as the firm was then called, that they became friends and, eventually, began “moonlighting together,” says Kieran. (“Much to the chagrin of Bob and Denise—and you can print that,” throws in Timberlake.)

In the early 1980s, both won the prestigious Rome Prize, Kieran in 1980-81 and Timberlake in 1981-82, which brings with it a year-long fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. They established their practice in 1984. “We had small projects—residential renovations, a jewelry store, a car dealership, the typical fare for young architects,” recalls Kieran, but from the beginning they were determined “to have a plan—not just take what came our way but go get what we wanted to do.”

High on that list was work for educational and cultural institutions, which make up the bulk of their client list today. Besides Penn, their current projects for academic clients include four residential college renovations at Yale University; a three-building complex at Middlebury College, “very much an extension of the landscape of Vermont,” that includes residences and a dining hall that will be naturally ventilated, with a green, planted roof on the dining hall; five buildings at Sidwell Friends School, an independent school in Washington, that also has a “very strong sustainable agenda,” with natural ventilation, green roofs, and solar collectors; and a study for Stanford University, their first project in California, to look at several existing buildings with an eye toward creating a “a more comprehensive and cohesive student commons/union area.”

But “12 or 13 years passed with us really sort of struggling, going after commissions and so forth, before the work began to resonate and folks trusted us with buildings at scale,” says Timberlake. In the firm’s early years, they avoided architectural competitions, feeling that “doing a lot of drawing work” was less important than actually building something.

“We are very much hands-on,” says Kieran. “We don’t know how to think without making.” This “passion for putting things together,” he says, threads through their work up to and including Levine Hall “—and continues to evolve,” adds Timberlake. “It’s an interest in materials, and an interest in how things work—tectonics, as architects like to put it—and it’s a core philosophy within the work.”

They take the same holistic view of managing their firm, which now includes about 50 employees in an airy, loft-like space they designed—formerly the studio of a local television station—located a few blocks from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Rather than a clear division of labor, in which, for example, there is one “business” partner and one “design” partner, Kieran says, “underlying the model we went after, for better or worse, was a belief that you can’t segregate the world that way and have good buildings and happy people in the end. As imperfect as we all are in our skills, we still need to do it all.”

In the field, “a decision about a technical matter is also a decision about an artistic judgment, and it is also a business decision—about liability, for example, about cost,” he adds. “If we can’t control all those things holistically, then we’re not architects—we’re artists or businesspeople, but we’re not architects.”

In addition to varied responsibilities at the firm, a good balance between work and family is another creative plus. “What really has enabled Steve and me to do what we’ve been able to do is that we have spouses who also have businesses—not together—but who are active and have their own work that they pursue, and then also families,” says Timberlake.

He is married to Marguerite Rodgers, an interior designer whose portfolio includes several high-profile Philadelphia restaurants, including Rouge, Striped Bass, and Susanna Foo, as well as residential work. They have a six-year old son named Harrison. Kieran and his wife, Barbara Degrange Kieran, a vice president with reseach-and-consulting firm National Analysts, have two children: Christopher, now in college at Vassar, and Caitlin, now in high school. Rather than one or the other partner running a given project, the model that they have moved toward has an associate in charge “with us acting as design partners,” says Timberlake. “This allows Steve and me the freedom to collaborate and employ the collective intelligence of the firm on projects.”

This collaborative model is becoming more common among architecture firms, serving as a useful counterweight to the prevailing cultural value placed on specialization. “We think specialization is the death knell,” Kieran says.

“There was a time when the complexity of the world and the materials we had to deal with, the sciences involved, was significantly simpler than they are now,” he explains. “As an architect you were not just a designer; you were a materials scientist, you were an engineer, you were the builder, you were the conceiver.” This era yielded “some extraordinarily profound art that we all still, when we get the chance, run around the world trying to find and see because it moves our souls.”

One of the “saddest legacies” of Modernism, in architecture and other fields, he adds, is the “belief that to advance knowledge we all have to quadrant ourselves into a narrow specialization.” While this may (or may not) be fine for fields such as medicine, for example, “What’s lost for architects is the ability to bring the whole of an artifact as complex as a building to life in a holistic and integrated way.”

The profession has narrowed its focus over the last 50 years, says Timberlake, both through fragmentation into sub-disciplines and by deciding that “we don’t want to design a certain aspect of the building, that’s for somebody else.” For example, landscape architecture is “part and parcel of the program that makes up Levine Hall,” he says. “Engineering is very much a part of the architecture—that’s why the wall, the infrastructure in that building, and the choice of structural systems is very much celebrated. All of that’s an act of design, in collaboration with the engineers and the landscape architects that participated in that team.”

The argument that the profession should take on less has “led to a failure in quality, in control, in an exercise of making products that have human scale,” he says. “And that’s why we’ve been practicing an integrated philosophy, and now in this new book we argue for it.”

Refabricating Architecture: How Manufacturing Methodologies Are Poised to Transform Building Construction, published this month by McGraw-Hill, is their manifesto for a new architecture, in which the profession will reclaim its central role in creating buildings by adopting practices developed in other industries such as shipbuilding and automotive and aircraft manufacturing. (The partners have previously collaborated on Manual: The Architecture of KieranTimberlake, published by Princeton Architectural Press in 2002.)

Refabricating Architecture came out of research made possible by the Benjamin Latrobe Fellowship, a two-year grant of $50,000 from the American Institute of Architects College of Fellows. The award, for architectural design research, was established in 2001, with KieranTimberlake as the inaugural winner. In the first year of the fellowship, they crisscrossed the country—they mention Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, then Jack Kerouac as a better comparison—meeting with managers, engineers, and product designers at companies like Boeing, DaimlerChrysler, and the shipbuilder Kvaerner in an attempt to identify transfer technologies that could be adapted to building design and construction. “They basically have this integrated model, and it’s had a huge impact on the quality of what they can do,” says Kieran. “It is largely a computer-based model that allows for integrated, cross-disciplinary discussions and working together across continents.”

The partners also helped to organize and were featured at The Architectural Record Innovation Conference, held in New York on October 8-9. Speakers included Nobel Laureate (and former Penn physics professor) Alan Heeger of the University of California, Santa Barbara; Segway inventor Dean Kamen; and representatives from NASA, Lockheed Martin, and Walt Disney Imagineering, among others. “By having people other than architects present what’s going on in their worlds, followed by a roundtable that’s directed by architects in each of those sessions, the idea was to talk about ways of integration, ideas that might be transferable, strategies that we can learn from,” explains Timberlake.

Besides supporting their investigations into innovations in other industries, the fellowship also provided funds that allowed them to hire an in-house research staff, a distinct rarity for a U.S. architecture firm. Corporate grants have supplemented this support more recently, and “if it turns out it can’t support itself, we’ll support it,” says Kieran.

Both men place a high value on teaching, whether in their written work, mentoring the members of their firm, or in the classroom. The design lab that they’ve taught at Penn for the past four years, they say, has been valuable both as a place to share their expertise and try out new ideas.

The lab suits their philosophy better than a conventional design studio, says Kieran. “It allows us to set the agendas and direct the work, and it’s a way of combining our research interests with academics and having students learn in a different and more directed way.” That helps justify the time they spend teaching—“since we are, after all, mostly practicing architects”—as well as giving students insight into the world “of actually making things.”

In contrast to the view that “architectural form is everything,” which was prevalent when they were in school and still exists in some quarters, says Timberlake, “Our philosophy is really that form is one leg of a triad. Vitruvius’s term is ‘Commodity, Firmness, and Delight,’ and we’ve always subscribed to that: It has to be useful, it has to work and be maintained and last a long time, and it has to be beautiful. If you’re only solving for beautiful, you’re forgetting the other two legs of that triad.”

Their Latrobe Fellowship proposal had its beginnings in lab discussions about transfer technologies, and another thread running through all four labs has been a search for new building materials. “Most walls are built up of thousands of individual parts, multiple layers, and they’re really thick,” says Kieran. What if walls could be thinner, they asked, with the elements to provide shelter, climate control, light, and power already integrated into the wall when it arrived at the construction site?

Their answer is SmartWrap, “a mass customizable print façade” touted as “the building envelope of the future.” Only millimeters thick, it is made of a polymer material—think plastic soda bottles—combined with tiny components called phase-change materials (PCMs) that control temperature, organic light-emitting diode technology (OLED) to provide lighting and information displays, and solar cells to collect power. These components are printed or imbedded in the polymer using modern technologies for printing and lamination. SmartWrap “very much comes out of the laboratory, out of the collective intelligence of many students, ourselves, outside collaborators, and invited guests over a period of those laboratories,” says Kieran.

From August 15 through October 10, a 16-foot-square and 24-foot-high SmartWrap pavilion was exhibited in New York at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum’s outdoor terrace and garden as the first in its Solos exhibition series. (It withstood Hurricane Isabel, which made its way up the East Coast in September.) And from January 24-April 4, SmartWrap will be set up in the lobby of the Institute of Contemporary Art, the firm’s first exhibition on Penn’s campus.

A central theme in Refabricating Architecture has to do with technological advances that have made possible a seeming oxymoron, mass customization. For example, SmartWrap can be printed in a variety of patterns and can even change appearance according to climate conditions, and the manufacturer of the Levine Hall curtain wall was able to provide a range of windowpane patterns to give the units a varied appearance without slowing down the production schedule. With such corporate partners as DuPont, the firm has researched various types of modular construction.

“That thread is not only in the studio but in the full-time research that we’re doing here. Much of that research we’re trying to apply,” says Timberlake. “We’re building modular bathrooms and modular vanities for clients. We’re building a whole building that way for Yale.”

In that project, the university’s chief financial officer told them that “more money had to come out” of a building project without compromising quality. “If you grew up the way we did, you’d just say, ‘You can’t do that. If you want more quality, you have to spend more.’ But at Boeing and in the automotive industry, nobody does that.

“Well, we said, ‘We’re glad you asked. Here’s an idea for an off-site fabrication’” that would save money and installation time, and also was of “exceptional quality,” Kieran recalls. “We were able to do that because we had done the homework and the research. We got DuPont to pay us to do a prototype. That makes all the difference to success. Those that are prepared, succeed—and the research labs here and at Penn allow us to be prepared.”

With opportunities “to teach and also to build,” Penn has offered the partners “a direct link back into the Penn community, and an active link, a participating link,” says Timberlake. “Oftentimes, it’s the undergraduates that have that connection back into their alma mater—and Steve and I have that with our undergraduate schools as well—but I think we have a very direct connection to Penn and the Penn community.”

As at Penn, a lot of their work these days deals with “collections of buildings,” says Timberlake. “They are urban-design scale projects that involve not any single element on campus, but really remaking the campus.”

In whatever realm, “we look for the interesting project,” he adds. “Often people come to us with difficult problems, and they want the difficult problems solved. Those are the ones that intrigue us.”