On not speaking Arabic.

BY MONA HAGMAGID

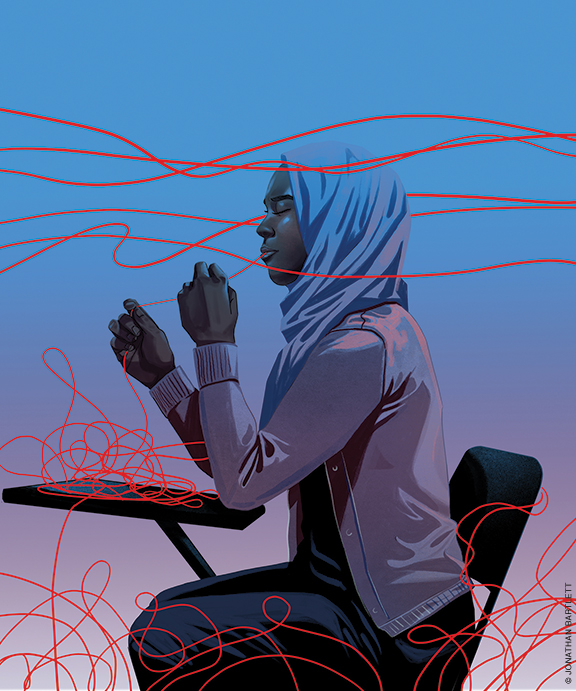

Recently I was flipping through a class notebook and found this written amidst last year’s philosophy notes: “My Arabic is the beginning of my shame. It is emptiness.”

I do not speak Arabic. My father does, and my grandmother does, and so do my aunts and uncles and cousins—whom I have not seen in nearly a decade. When they call and I answer the phone, we never get beyond the same three questions: How are you? “Tamam.” How is school? “Tamam.” Where is your father? I place the phone on the counter and call upstairs.

It is infuriating, speaking in circles, speaking like strangers, speaking so rarely. I have so many things to say and lack the right words to say them. Every letter is painful and every day in Arabic class is so terribly bittersweet.

Not being able to speak Arabic leaves me feeling fraudulent in spaces where I mention I am Sudanese. When I do, I do it slowly, letting my mouth feel out the sound it makes on my tongue, trying not to choke as I swallow the nagging aftertaste that tells me that this lineage is not really mine to claim.

Many people study Arabic just like I do, in a secular university classroom, poring over Al-Kitab and shuffling between Google Translate and the digital Hans Wehr Dictionary. Many people want to learn this beautiful, stunning, sweet-sounding language, people who want to conduct international business or go into foreign policy. Arabic is trendy these days. It is lucrative. It is smart. It is a language that has shaped the world, and people here like to shape things, so it makes sense why the classroom looks the way it does. Some Muslims take this class to learn to read. They want to feel more authentic in their faith, they want Arabic to connect them to God and His book and His messenger.

I too, am Muslim. I like to believe that I, too, am drawn to the scripture and sacredness that Arabic letters unlock. But my desire for Arabic feels more urgent than that: rawer, more instinctual, rooted deep within me. I am simple and selfish: I want to master this language to speak to my family. I want to be able to call my uncle and not wait for my father to come down the stairs and save me from the agony of our shallow conversation. I want to be able to laugh and respond at Sudanese community events, instead of clinging to the walls or my sisters in silence. I want to be able to teach my children these letters and these sounds, and sing them these songs and tell them these stories so that they will never feel this stinging shame the way I do.

Being Arabic-less is a part of the way I am in the world. I wake up in the morning Arabic-less; I brush my teeth and wrap my hijab in the mirror as I drape my broken vowels over my shoulders to take with me as I turn out the lights and pull the door. I walk through campus Arabic-less, I eat my lunch still fumbling between past and present tense, I study my Psychology textbook while aware that my Arabic handwriting remains scribbly and tired.

I come to Arabic class worn out before I reach the door. I sit down gratefully. I try. I can read and I can recite and I can speak to my white classmate—who smiles at me through his American accent, making me wonder if that is how I sound to my grandmother when I spit out a sentence: sweet, good hearted, but so starkly foreign.

My Sudanese friend shows me YouTube videos in Arabic in her dorm room. I have been studying this language for 12 years now and I cannot understand a word they say. She translates and smiles and laughs at just the right moments and I want to burst into tears. I watch the girl’s face through the screen, my eyes straining and stretching and burning as I desperately study her lips. They move fast and quick, producing a swift flow so different than the dragged-out way I speak. Arabic pitter-patters off her tongue like rain and I still haven’t learned the word for storm yet and the longing feels like too much in my chest.

Sometimes I wish I could let myself give up. Come to terms with the gruesome reality that this language is too fast and too quick and too much like a hurricane for me to ever be able to get it. I try to convince myself that it is okay, that I am not a failure, that I do not need to know how to read Arabic poetry to be able to call myself a poet. That I don’t have to know how to bend and stack Arabic words the way I do with English ones to be able to tell my aunt that I love her and my grandmother that I miss her, and my cousin that she is growing up so beautifully and that I wish my feet could land in Khartoum tomorrow. But it doesn’t work. The pain is too much to bear and I want to be healed and emerge and shed this shame. I want to conquer Arabic, to cradle it, to admire it, to claim it as my own and no longer feel like an imposter when I say my name out loud.

This language is an ocean and I am drowning and I cannot form enough sentences to stay afloat. I watch others sail by in ships sealed together with all 10 verbal patterns, dusted in their mothers’ accents, and I am filled with desire. I want to be able to know my own heritage, not through translation, or subtitles gifted to me out of pity. I want to hear it in its own sound, raw, real, and beautiful. And I want to be able to reply to it. In my own voice. In my own words—without shame, or hesitation, or fear—in Arabic.

Mona Hagmagid is a College junior studying Philosophy and Africana Studies and is a member of the campus spoken word collective, the Excelano Project.

Hi Mona, I am sad that you feel so much pain because of not being able to speak Arabic. I was born and brought up in Egypt and am fluent in Arabic, however, I don’t use it very much at all. I feel it slipping away from me every year I use it less. I am a hospital pharmacist and don’t really have an opportunity or need to use it in my daily life. I have a solution for you though; immersion! That is the only way you will master it, when you live it all day long with people who speak the language. It becomes part of your being and your mind. The only way to overcome this painful roadblock is to take 3 months or more to live in an Arabic speaking country and take additional classes in that country. You can overcome and master, you just need the right solution and tools. Good luck to you, I know you can do it. Email me if you need more support.

Wonderful article. I speak my language yet miss being able to converse in a more pure form adequate for literary circles of which my extended family is a part of . Your words describe my feelings about reading/writing poetry in my language. The feeling of having been left out; having missed the train.

Very proud of this young lady wonderful article