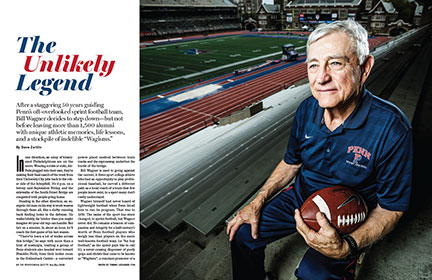

After a staggering 50 years guiding Penn’s oft-overlooked sprint football team, Bill Wagner decides to step down—but not before leaving more than 1,500 alumni with unique athletic memories, life lessons, and a stockpile of indelible “Wagisms.”

By Dave Zeitlin | Photo by Tommy Leonardi

In one direction, an army of bleary-eyed Philadelphians are on the move. Wearing scrubs or suits, AirPods plugged into their ears, they’re making their final march of the week from their University City jobs back to the other side of the Schuylkill. It’s 6 p.m. on a breezy mid-September Friday, and the sidewalks of the South Street Bridge are congested with people going home.

Heading in the other direction, an energetic old man on his way to work weaves through them all, like a shifty running back finding holes in the defense. He walks briskly, far brisker than you might imagine 80-year-old legs can handle. But he’s on a mission. In about an hour, he’ll coach the first game of his last season.

“There’ve been a lot of walks across this bridge,” he says with more than a hint of nostalgia, trailing a group of Penn students also headed west toward Franklin Field, from their locker room in the Hollenback Center—a converted power plant nestled between train tracks and the expressway, underfoot the bustle of the bridge.

Bill Wagner is used to going against the current. A three-sport college athlete who had an opportunity to play professional baseball, he carved a different path as a head coach of a team that few people know exist, in a sport many don’t really understand.

Wagner himself had never heard of lightweight football when Penn hired him to run its program. That was in 1970. The name of the sport has since changed, to sprint football, but Wagner never did. He remains a beacon of compassion and integrity for a half-century’s worth of Penn football players who weigh less than players on the more well-known football team (or “fat boy football,” as the sprint guys like to call it); a never-ceasing dispenser of goofy quips and clichés that came to be known as “Wagisms”; a constant promoter of a program, sport, and league often on shaky ground; a legend in the eyes of the more than 1,500 people he’s coached.

But Wagner is 80 now. The 2019 campaign marks his 50th in charge of Penn’s sprint football program, making him one of the longest-tenured coaches of any team, ever. The team plays in a stadium celebrating its 125th anniversary. All of the numbers were just so … round. If there was ever a time to walk away, it was at the end of this season.

That’s what he told his current players in late August, the tears starting to flow as soon as he gathered them in the locker room for a talk he’d been putting off for years. “Every time I think of that word, I cry,” he said. But he vowed that the word retirement wouldn’t stop him from still being around the program, from watching everyone graduate, from making his final season a special one.

Three weeks later, with the team’s 2019 opener versus Army set to kick off, Wagner is back in the Hollenback locker room, showing off the refurbishments made possible by alumni donations—the lifeblood of the program. He walks to his office next door, where all of his assistant coaches—mostly former players—are enjoying each other’s company. Someone reminds Wagner, who’s called “Wags” by just about everyone who knows him, about his promise to play in next year’s alumni game, the annual event that pits the current team against former players, some in their 60s [“Varsity Rules,” Nov|Dec 2013]. In a flash, Wags gets down in a quarterback stance and mimics a pass.

“He’s a fantastic athlete,” says Steve Barry W’95, recounting a story from his playing days when Wagner, frustrated with his quarterback during a training camp practice, threw down his clipboard, took over at QB, and fired “just a perfect strike to a guy 35 yards downfield. He then picks up his clipboard and yells, ‘Now that’s how you do it!’” Dave Hubsher EAS’11 tells an almost identical story of Wagner doing the same thing more than a decade later. “That was my this guy is crazy realization,” laughs Hubsher, who decided to stick with the “crazy” coach as a part-time assistant.

Wagner, who also served as the Penn baseball team’s pitching coach for 35 years, is probably even better throwing a baseball than he is a football. And equally competitive, too. Until a couple of years ago, he was playing in a hardball, fast-pitch baseball league against players half his age. Not long before Wagner hung up his cleats, sprint football offensive coordinator Jerry McConnell visited his South Jersey home—which sports a bannister made of baseball bats—and asked why he was covered in dirt. “Headfirst into second, Jer,” Wagner told him, as if there was nothing out of the ordinary about a man in his 70s sliding to beat a tag.

Wagner took that same attitude into Citizens Bank Park on September 10, when he was recognized for his coaching career by the Philadelphia Phillies—and came away absolutely disgusted with himself that the honorary first pitch he threw from the mound bounced before reaching the plate. “I can take a baseball right now and fire the damn thing to second base from home plate!” says Wagner, who marked what’s typically a lighthearted occasion by uncorking his famed “knuckle drop,” a pitch he says helped put former Penn baseball pupil Steve Adkins EAS’86 into the Major Leagues. “That pissed me off!”

Almost as disappointing: attending that Phillies game prevented him from putting his team through its paces at practice. Wagner thinks it’s the only practice he ever missed in 50 years. Yet as he walks from Hollenback to Franklin Field three days later, he’s confident his team is well-prepared to take on Army, a perennial juggernaut of the Collegiate Sprint Football League (CSFL).

Early in the Friday night opener, Penn looks overmatched. But after a tough first half in which they fall behind 14–0, the Quakers storm back to make it 21–21 early in the fourth quarter, with a boisterous crowd of roughly 500, along with the Penn Band and cheerleaders, urging them on. Unlike some aging coaches who might spend the twilight of their careers sitting upstairs in a booth, or acting as a figurehead, Wagner is on his feet the whole time, pacing the sideline, his booming voice—“TIMEOUT!”—piercing both ends of the stadium. “He knows he still has the energy, which is making it harder,” says his wife, Connie, who takes photos at every game. Adds senior quarterback Eddie Jenkins, “By the way he acts, you’d think he’s 25 out there.”

Throughout the contest, Jenkins can’t help but think of Wagner’s emotional pregame talk—and how the coach broke down crying, for the third time in three weeks. “We want to win for him,” the quarterback says, his helmet furnished with a “50 Wags” sticker, like all of his teammates’. “That’s what this season is all about.” After running for all three of his team’s touchdowns, the senior finds himself driving his team down the field in the final minute, the Quakers trailing 24–21 and out of timeouts. He completes one long pass to the Army 40-yardline, then another to the Army 28. Thirteen seconds remain. Penn has time for one more play, maybe two. The pocket collapses on Jenkins and he’s off running, needing to get out of bounds to stop the clock or into the end zone to win the game. He’s tackled short of both, and time runs out on what could have been a dream victory. “If the kid didn’t tackle him, he’s in the end zone,” Wagner laments afterwards. “That would’ve been one hell of an ending, wouldn’t it?” His brain is now churning, thinking of all of the other endings over 50 years. “It would have been the best,” he adds.

About 30 minutes later, save for his wife and a couple of kids diving around the Franklin Field turf, Wagner is alone with his thoughts inside the stadium. He’s just told his players how proud he was of them, how they should aim to meet Army again in the CSFL championship (which this year will be held at Franklin Field, on November 8th), how they would punish Cornell the following week if they played as well as they did in the second half (which they did, walloping the Big Red, 61–7, on September 20, behind seven Jenkins touchdowns). But as any coach might after a tough loss, he’s questioning some of his late-game decisions as he leaves the field, including whether he should have tried for a game-tying field goal.

He looks up at the nighttime sky, pointing out that there’s a full moon on this Friday the 13th. Soon, while walking back over the South Street Bridge, his priorities shift. He passes one of his players, already showered and in street clothes, jogging back to campus. Another is holding two plates of food from the postgame tailgate party that parents put on outside of Hollenback. One more rides by on his bike. He stops them all, telling them to be safe. “He never puts on an act,” says former player and current assistant coach Chuck Hitschler W’73. “The players feel that. They feel that he has their back. He’s like having a father on campus—or a grandfather on campus.”

Before joining everyone at the tailgate—“the best in the league,” McConnell boasts—Wagner gazes across the bridge at the Philadelphia skyline, now illuminated red and blue. It’s been a long, emotional day. He knows there won’t be many more days like these, and everywhere he looks the longevity of his rapidly ending career is being put into perspective. “Sixty percent of that wasn’t there when I started,” he says, taking one more glance at the Center City skyscrapers before walking downstairs to fill his plate with pasta, meatballs, and wings.

“Love of the Game”

It was early in the 1970s, in Wagner’s second or third season as head coach, when Hitschler distinctly remembers sitting in the visitors’ “locker room” at Army West Point, which he and McConnell—now the team’s top two assistants—liken more to a garage than a locker room. There are no bathrooms; only two porta-potties outside. “You get sick from the smell,” McConnell says. If there was ever a time and place for Hitschler, a former wrestler who had to stop wrestling when he hurt his knee, to question why he was playing sprint football, it was then and there. Still, he perked up as Wagner began his pregame talk.

“All right, this is where you earn your scholarships!” the young head coach said.

Huh?

“Wait a minute, none of you guys are on scholarships,” Wagner continued.

“All right, there’s 40,000 screaming fans, and when you run out—”

He cut himself off.

“Actually there’s only a couple of hundred fans.”

Some murmurs in the locker room.

“All right, your girlfriends are out there—no, you guys are too ugly to have girlfriends.”

Laughter.

“So what the hell are we doing up here?”

A senior in the back raised his hand.

“Coach, Coach, I got it. It’s because we love to play football.”

“Well, that’s good enough for me,” Wagner replied. “Now let’s go have some fun!”

For Hitschler, that struck right at the “essence” of sprint football, a sport that most people don’t realize is varsity and, aside from mandating a weight limit on players (currently 178 pounds), has the same rules in place as regular college football. “You can walk around campus and you can have all of your sprint football stuff on and people still don’t know what that is,” says Hitschler, a longtime high school coach at Penn Charter who now serves as the Quakers’ defensive coordinator. “There’s no glory.”

“We play in front of a couple hundred friends and family,” adds Barry. “There’s nobody that’s going pro, or even getting scholarship money. It’s purely because we love football—and that is what Wags is all about.”

While it might be a cliché, love of the game was indeed all Wagner needed to coach the Quakers as long as he has. And although he grew up on the other side of the river in working-class Camden, ending up at Penn was almost predestined, too.

His grandfather was named Benjamin Franklin Wagner. So was his father, who instilled in him a love of sports from an early age. The oldest of five children, Wagner spent much of his childhood shadowing his dad to baseball games at the old Shibe Park or to Franklin Field to watch gridiron legends like Francis “Reds” Bagnell C’51. And like his father, he excelled at three sports: football, basketball, and baseball. He was so good at baseball, in fact, that coming out of Trenton State College, he was offered $3,700 by the Los Angeles Dodgers to play for their minor league affiliate in Spokane, Washington. But knowing that the opportunity for advancement in Major League Baseball (which then had about half as many teams as it does today) could be limited, he instead accepted an offer closer to home: coaching football, basketball, and baseball at Camden’s Woodrow Wilson High, which he had attended.

Wagner spent the rest of the 1960s teaching and coaching at Woodrow Wilson and at nearby Cherry Hill High School East. And when longtime Penn baseball coach Bob Seddon paid a visit to Cherry Hill to recruit one of his players, he also gauged Wagner’s interest in two coaching spots that had just opened at Penn: for the freshman baseball and lightweight football teams. Wagner ended up taking the plunge—but not before wondering: What is lightweight football anyway?

“I had to find out what it was about,” Wagner says. “And I found out really quick these kids were playing for the love of the game. Half of them had never played football when I first got here.”

Although lightweight football at Penn dates back to 1931—it was then called the 150-pound football team, and was launched to give smaller athletes a chance to compete at the collegiate level—most of the teams through the first half of Wagner’s tenure were indeed overmatched. “Back in the ’70s, it was a little more difficult because you never knew who was going to show up,” says Steve Galetta C’79 GM’87, one of the top running backs in program history and a member of the Penn Athletics Hall of Fame. Army and Navy, meanwhile, were “beating everyone up, looked bigger than anyone in the league, had 100 players at every game,” Wagner notes. J. Matthew Wolfe C’78 remembers that for the final game of the 1975 season, the Quakers traveled to Navy with an injury-wracked roster of about 25 players and that five of the seven offensive lineman limped to the line of scrimmage for the first play. They lost, 57–7. “It’s tough in a league where you have Army and Navy, in a sport that’s almost built for Army and Navy,” Wolfe says. “Everyone goes to service academies between 160 and 190 pounds, and they all played football in high school.”

Nevertheless, Wagner didn’t make excuses, nor did he treat sprint football like a second-class sport. His players might have been walk-ons with limited experience—but they still had to take it seriously. “He wanted to make sure it was clear this is not an intramural-type of program,” says George Heinze ChE’76. That meant following the rules. In one of the last games of the 1978 season, Wagner benched seven players for violating curfew the night before the game. “That was one of the toughest games I ever played in my entire life,” says Galetta, now a neurologist and professor at NYU who previously served as the sprint football team’s faculty advisor while working at Penn. “But those were life lessons.”

From a results standpoint, things didn’t improve much in the 1980s. But Wagner continued to build a culture—while seeking out more talent. Eric Furda C’87, now Penn’s dean of admissions, learned of sprint football when his high school coach in upstate New York received a letter from Wagner that was part of a mass mailing recruiting campaign. “I can say as a fact that I would never have been at Penn if it wasn’t for Coach Wagner,” says Furda, who won only one game in his four years on the sprint football team and practiced on a field—Murphy Field, where Meiklejohn Stadium has since been built—that was so sandy “the Mars Rover needed to go there.” (Former player and coach Nate Scott C’89 GEd’89 recalls that something did land there—MedEvac helicopters that he says interrupted practice for 10 minutes at a time.) And all of this was happening while Penn’s other football team was racking up Ivy League titles. “One win in four years—who the hell wants to do that?” Furda says. “Just his level of commitment to kind of stick through regardless—he’s a tough-ass guy in that way.”

It took 26 years but Penn finally broke through, sharing a piece of its first league championship under Wagner in 1996. (The Quakers went on to win titles in 1998, 2000, 2010, and 2016, going undefeated in ’00 and ’16). The big win of that ’96 season—and one of the biggest of Wagner’s career—came in the penultimate week when the Quakers stunned Army, 16-13, despite being outgained in yardage by a 354-99 margin.

In the aftermath of that victory, Wagner’s elderly father—who attended every game, even into his 80s and 90s—stood in front of the celebrating team (and next to longtime assistant coach Dan Harrell CCGS’00 CGS’03 LPS’08), proudly showing off his “Beat Army” shirt. The photo snapped in that moment remains one of the coach’s most prized possessions. “To know Wags, you have to know his dad,” says Harrell, best known for his former role as a Palestra custodian [“A Palestra Icon Hangs Up His Mop,” Sep|Oct 2012]. “Everything Wags got, he got from his dad. His dad was an old-school, hard-nosed guy. There’s no gray area with Wags. He’s not a bullshitter.”

Wagner’s father died, at 95, in 2004. At the end of that season, a new team spirit award was named in his honor, which Doug Pires C’05 was the first to receive. “I tell you, to this day, that was the most touching thing that’s ever happened to me,” Pires says. “This old guy in a wheelchair could pump the team up—just by his presence and what it meant to Wags.”

“If a Frog Had Wings … ”

A sampling of “Wagisms” collected by those who’ve heard the coach blurt them out over the years:

“If a frog had wings, it wouldn’t bump its ass when it hopped.”

“Don’t go falling out of any trees tonight.”

“If you don’t swing, you don’t hit.”

“How many times do you have to kick a dog in the ass before he stops pissing in the kitchen?”

“If you’re looking for sympathy, you can find it in the dictionary between shit and tears.”

Not all “Wagisms” are completely original, but it was the coach’s delivery that perfected the sayings and usually made the players laugh, even in moments when they were being reprimanded. “The great thing about a Wagism is he would yell it out in a moment of frustration and we’d be in the huddle like, What the hell did he just say?” says Scott, who went on to coach on Wagner’s staff for nine years. “There’s a lesson to be derived from that, but I’m not sure what it is.”

“He would always screw it up just a little bit,” says Barry, adding that Wagner also often mispronounced players’ names in hilarious fashion. “He’s funny,” notes former player Alan Fein W’76, “but I don’t know if he always means to be funny.”

At this year’s alumni game, Henrik Ager WG’93 (a native of Sweden who Wagner remembers coming out for the team with “a cigarette in his mouth”) shared a classic story of Wagner peeing at a urinal in a Princeton bathroom next to an opposing coach who told him, “Here at Princeton, we learn to wash our hands.” To which Wags responded: “At Penn, only the people who know not to piss on their hands are accepted.”

“It was something like that, yeah,” Wagner laughs. “We have some Princeton jokes.” A while back, he started a tradition of bringing a pumpkin on the road to Princeton (to match the color of the Tigers’ helmets), drawing a funny face on it, and then smashing it on the ground in the locker room. “I didn’t have to say anything,” he says. “They would get so fired up from that.”

Though Princeton drew most of his ire, he had a penchant for ribbing his own players too. Former CSFL Most Valuable Player Mike Bagnoli C’11 recalls a Brazilian kicker showing up for practice one day in a Cincinnati Bengals Chad Ochocinco jersey—before being promptly told by Wagner to run up and down the steps of Franklin Field. “It was all love there; just philosophical differences,” Bagnoli laughs. If Wagner was hard on someone, it was usually in a caring, avuncular way. He wasn’t afraid to bench a starting quarterback for violating a team rule, but he also permitted a player to skip practice to attend the World Series, or to fly back from a job interview in San Francisco the day of a game. When Bernie Lopez C’82, who says he was “essentially a nobody on the team,” decided to quit, Wagner respected his decision. When Lopez realized he’d made a mistake and asked to return, he “took me back, and he didn’t treat me any different than he did before,” says Lopez, now an emergency-medicine physician at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital who’s mentored past players interested in medical careers.

“He’s such a genuine, caring guy,” adds Bagnoli, whose uncle, Al, got along well with Wagner while serving as Penn’s “fat boy football” coach from 1992 through 2014. “You can meet alumni from 30 years ago and you have the immediate reference point of Wags. And he’s been the same guy.”

Bagnoli was one of many former players at this year’s alumni game—where fierce allegiance toward Wagner was on full display. So was the head coach’s vitality. Near the end of the exhibition contest, with the alumni team losing by almost 40 points and the current squad’s deep reserves on the field to close it out, Wagner was still looking at his clipboard and calling offensive plays. “I debated even if I should say hi,” says Barry, who approached Wagner—briefly—in the fourth quarter. “I waited until they were on defense.” Only later did Wagner learn that his team had been trying to put up 50 points, in honor of his 50 years. They came close, winning 44–0. “Those dogs,” Wagner told the assembled crowd at the postgame barbeque on Shoemaker Green, outside of Franklin Field. “I said, ‘Don’t you dare.’”

The final score probably meant little to the alumni in the end. Afterwards, everyone just wanted to shake Wagner’s hand, or take a photo with their old coach. “Aw, he’s so cute,” one alum’s girlfriend said of Wagner, as he made time for everyone, remembering specific plays from decades ago and saying “We go way, way back” to more than one of them. “He’s the best,” the former player responded.

By the time he got to Shoemaker Green, Wagner was still holding his clipboard, still full of energy. “I’m not a crybaby—I want to establish that right now,” he said. But by the end of his speech, as everyone rose in a standing ovation, he couldn’t help but again wipe away a few tears.

“The thing we all have—the common bond—is Wags,” says Dan Malasky C’97, who kicked the winning field goal in Penn’s momentous win over Army in 1996. Now the chief legal officer for the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, he flew in for Penn’s game versus Army this season, only to fly back to Florida the very next morning. “It doesn’t matter what year you played for him, what decade you played for him, what position you played for him—we all have a similar bond because we played for him.”

And it’s been that bond that not only kept Wagner happy at Penn for, as he likes to say, 62.5 percent of his life—it also kept the University’s sprint football program afloat when it could have easily sunk.

“There’s Nobody Like Him”

About 20 years ago, at the team’s end-of-year banquet, Wagner’s friends and former players surprised the coach with a friendly roast. When it was his turn to speak, his wife recalls, Wagner said it almost felt like a retirement ceremony—which caused him to break down crying just at the thought.

“He’s been anticipating this day for 20 years,” Connie says, “and it hasn’t gotten easier. The funny thing is that maybe for the last 15 years, he keeps saying, ‘I’ve got a great group of freshmen coming in, I want to see them graduate.’ You can only do that so many times. Then he got more practical, and it was two more years. Then he started saying one more year.”

“I have asked him probably for the last five years, ‘When are you going to retire? This is a lot for you. You need to be able to go relax and travel,’” says his daughter Beth Coyne C’86, who played lacrosse and field hockey at Penn, and has three daughters who attend or have attended the University. “But he just wanted to make sure he left the program in a strong place.”

Ensuring the program’s long-term viability has always been a central theme of Wagner’s tenure. He first learned of the precarious nature of sprint football during his second year in charge, when he says then-University president Martin Meyerson Hon’70 threatened to drop the sport. Wagner helped rally alumni to contribute financially to stave it off and save his job. But the advent of Title IX—the 1972 federal civil rights law that, in part, mandates equal access for men and women participating in college sports—kept the program in danger for many years. As colleges strived to have the same number of male and female athletes, maintaining two football teams (with upwards of 150 combined players) seemed harder to justify. Other sprint programs were dropped. (That included, most recently, Princeton, which was in the midst of a 106-game losing streak when its program was discontinued in 2016—much to the chagrin of Wagner, who, “pumpkin head” jokes aside, valued Penn’s rivalry with its fellow charter member and believed the Tigers’ program was being undercut by its own athletic administration.)

During Steve Bilsky’s term as athletic director in the 1990s, Wagner says “they questioned gender equity,” which led him to agree to limit his roster to 52 players (below the league maximum). Meanwhile, the sprint football sports board rushed to support. “Bilsky came to us and said we’re going to have to raise a shitload of money to keep this program going,” recalls Fein, the co-chair of the board who notes they’ve since raised more than $2 million to endow the sport. “I do a lot of fundraising in Miami,” adds Fein, an attorney, “and this is the easiest fundraising I’ve ever done.”

And that’s because of Wagner, who draws an “amazing amount of loyalty to this program by alumni and other people this program touched,” Wolfe says. Pires, another board member, adds that he’s never heard Wagner specifically ask for money, noting that it “just organically happens” through his presence. “He’s just a uniting type of person. I don’t know what it is but people are drawn to him,” says Pires, who, like many former players, participated in phone-a-thons in college. “You’re a kid calling these donors and alumni, disturbing their dinner. And all you have to do is drop Coach Wagner’s name, and all of a sudden they’re like, ‘What do you need? I’ll write you a check. How’s the team doing?’”

It’s gotten to the point where last year the program’s direct costs (operating expenses and coaching staff compensation) were 100 percent funded by the combination of annual fundraising donations and income from endowments that the sprint football community has established, according to Penn’s athletic department. Players used to have to buy their own cleats and sweats; now they have a recently renovated locker room and modern equipment. And after league membership dipped to as low as five following Princeton’s demise, Wagner helped rally new teams to the CSFL, with several smaller colleges joining mainstays Army, Navy, Cornell, and Penn to create a 10-team league with two divisions.

“I consider this team a bunch of survivors,” Wagner says. “We’ve survived money, gender, fields—and we’re still here. We’ve been around since 1931.”

Before making his retirement decision, Wagner—whose head coaching position was endowed in 2014—also made sure a succession plan was in place. That includes funding for a full-time assistant coach, a director of operations, and a new head coach who will be named, from his current staff, after the season. Along with Hitschler, his crop of assistant coaches include former players Hubsher, Sam Biddle C’11, Mike Beamish EAS’15, and Tom Console C’19. “It speaks to Wags’ vitality,” says Hubsher, “that all of the guys who were his peers started dropping one by one and he’s the last one standing. Everyone he’s got left are people he’s coached.”

Though he’s retiring, Wagner will remain around the team, as a board member and head coach emeritus. He still hopes to look in on the alumni mentoring program he calls “one of the better ones in the whole school” and plans to attend every alumni game, whether in pads or not. “He left this ripple effect on all alumni,” Pires says. “And it’s up to us to carry on his legacy.”

Perhaps the only thing Wagner might not miss are the Friday bus trips to and from Cornell without the luxury of a hotel stay—especially the one in which the team didn’t get back to Philly until at about 7 a.m. the next day because of a weather delay and six overtimes. Or when all of the coaches and players had to “get out and push the fucking bus into the middle of the street” at Army. Or that time at Navy the team had to get changed in shifts in a media room, because the locker room was taken.

But, in some ways, the unglamorous parts of sprint football—which is to say, almost every part—made the whole journey even more rewarding for someone who earned a part-time salary for much of his time coaching two sports at Penn while also teaching at Cherry Hill East. And all of the assistants he’s had over the past 50 years, most of whom arrive for the team’s daily 6 p.m. practice at Franklin Field from their regular day jobs, have tried to follow his lead.

“There’s nobody like him,” says McConnell, the grizzled football man holding back tears. “I’m very fortunate to have had the opportunity to be around him, to have my family be around him. He’s just a great man.” Adds Harrell, also choking up: “He’s the nicest man I’ve ever met in my life. Loyalty is a two-way street, and he’s loyal to everybody.”

Wagner’s former players, even those who’ve moved far away and might not feel the same connection to Penn as they once did, have the same kind of loyalty toward him. “He’s somebody who oozes leadership and dignity and integrity,” says Tim Ortman C’01, who holds several program rushing records. “For 50 years, he’s tied everyone together. I hope he stays in the same role keeping all of the alums intertwined. I think he’s the only man who can do it.”

“Coach Wagner’s legacy is going to be that he’s kept this program here at the University of Pennsylvania,” says Furda, who proudly displays several pieces of sprint football memorabilia in his office.

“Now it’s time for another coach. But this is always going to be Bill Wagner’s program.”