What would you do if you ran a city facing a $1 billion budget shortfall over the next five years, and the law required you turn the red ink to black before summer vacation? Bear in mind that your plan has to pass muster with a governmental oversight authority. Otherwise the state might just cut your city out of its own budget. And that’s only the beginning of your problems. The stock market just wiped out a third of your city’s pension fund, and the recession has depressed annual tax revenues by something like $100 million.

Oh, and one more thing. This $1 billion deficit, it’s the second one you’ve faced in three months. The easy fixes are gone. Squeezing the line items for paperclips and Post-It notes isn’t going to yield any more juice. If the last go-round was a root canal, this time you’ve got an appointment with Laurence Olivier’s sadistic Nazi dentist from Marathon Man.

So really, what would you do?

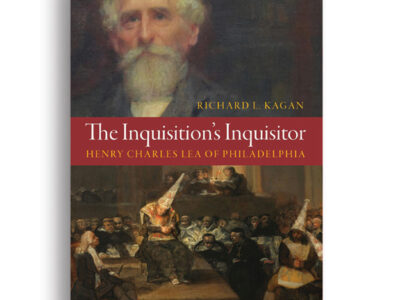

That’s the question that was put to 1,700 Philadelphians by the Penn Project for Civic Engagement (PPCE) in February. The month before Mayor Michael Nutter W’79 was charged with producing a new budget plan to address the city’s financial turmoil, the PPCE orchestrated four citizens’ forums that have no clear precedent in Philadelphia, or any other major American city.

They were collectively branded “The City Budget: Tight Times, Tough Choices.” At each one, participants were handed a dense two-page worksheet. One side detailed service cuts ranging from closing park fountains to laying off 1,755 police officers, along with a point value representing the savings each measure would produce. The other side laid out the revenue gains associated with a variety of tax hikes. After an introductory panel discussion that illuminated the main ways Philadelphia gets and spends money, the assembly split up into breakout groups averaging about 25 people.

For the next 90 minutes, each group had a gut-wrenching goal: trim 100 points out of the city’s budget to restore balance. Every decision would require at least a majority vote.

Although there’s an unavoidable selection effect when it comes to any public meeting—night-shift workers, overstretched parents, and residents with little English are seldom in attendance, to name just three groups of taxpayers—the PPCE events drew remarkably diverse crowds. The South Philadelphia forum burgeoned with pinstripes and wingtips, headscarves and cornrows, ball caps and pearl strings, habits and clerical collars. A subsequent data analysis showed that virtually every age, shade, and income level was represented.

For any Philadelphian who’s ever witnessed a local neighborhood-association meeting devolve into shouting and balled fists, in other words, it looked like a recipe for disaster. Or possibly an exercise in political theater, which was one criticism leveled at a series of town-hall-style meetings Nutter had headlined a few months before.

“Those town hall meetings are designed to create one kind of conversation,” says PPCE director Harris Sokoloff. “The mayor gets up and makes a presentation. People listen. And then there’s a whole lot of what people call ‘Q&A’—which is really more like, ‘I’m going to tell you what I think.’ And if there’s a question, there’s going to be, ‘Don’t you agree?’, or, ‘How could you be so stupid?’ But it’s always a bunch of citizens lining up to advocate for their one thing.”

The citizens’ forums were supposed to be different. The idea was to get people to step back from single issues and confront the tradeoffs soon to be faced by Nutter and his budget office. “The first goal was to inform citizens about the budget process and the nature of these decisions and tradeoffs,” Sokoloff says. “The second was to provide information, guidance, and input to the people who have to do that budget work, about where the citizens are—not as individuals, but when they work together, where they would be.”

In South Philly, Sokoloff outlined the expectations for the night. A grant from the William Penn Foundation, with additional support from the Lenfest Foundation, had provided for trained moderators to facilitate discussion in each breakout group. The mayor’s senior staff would pop in and out of each room, mainly to listen, but also to answer factual questions. Nutter himself had not been invited. “This is citizen work,” Sokoloff explained. “This is not about the mayor.”

That said, Nutter had pledged to incorporate the results of these forums into his budget plan. That’s a reversal of the usual custom in Philadelphia. Citizens typically have to wait until after a proposal has been crafted to have their say. This time they’d been promised a voice in advance.

If there was one take-away lesson from the enterprise, it’s that few citizens are equal to the task of making Philadelphia solvent—at least not in 90 minutes. Out of 53 breakout groups, none reached 100 points, and only a small handful topped 90. One achieved a mere four points.

Yet with the possible exception of that last dysfunctional cohort, it wasn’t for lack of seriousness. Participants earnestly and patiently tackled issue after issue, sorting each potential service cut or tax hike into one of four* buckets: from “Low Hanging Fruit,” which required a 75 percent vote for passage; to “No Way, No How,” a repository for intolerable sacrifices such as closure of a city-run nursing home.

The most popular move—unanimous, in fact—was refusing to maintain Lincoln Financial Field until the Eagles franchise agrees to pay over $8 million in back rent on Veterans Stadium. “Tell you what,” quipped one wag. “If they get to keep the money, they have to spend it on a good wide receiver.”

Other issues were harder to tease out, but several themes emerged. One of the clearest was an unwillingness to suspend services that impact the most vulnerable citizens, especially children and the elderly. A decisive majority of the breakout groups put cuts to homeless shelters, public health services, parks, and recreation centers off limits. There was also reluctance to cut firefighters or police officers, but some groups managed to swallow that bitter pill. Together, those departments account for nearly one-fifth of the city’s expenditures.

Conversely, participants showed a remarkable willingness to raise their own tax bills, given that Philadelphians already suffer the second-highest individual tax burden among American cities. Increases to the parking tax and wage tax (which is currently 4 percent) won more support than hikes to sales or property taxes.

“That was a surprise to me,” Nutter said in an interview on WHYY, Philadelphia’s NPR affiliate, after PPCE released the data from the forums. (WHYY was a partner in the project; its executive director of news and public information, Chris Satullo, is a co-founder of the PPCE.) “The number of citizens who responded on their own that they would consider paying more if it meant not having so many cuts in critical areas—police, and fire, and libraries, and recreation centers, and our swimming pools—I was certainly surprised at that.”

It also represented a dilemma for the mayor. Nutter has been a proponent of lowering Philadelphia’s wage tax since his years on city council. Ultimately, he rejected the collective wisdom of the “Tight Times, Tough Choices” participants in that respect. The budget he presented on March 19 protected many of the services that inspired support at the forums, but proposed to pay for them by temporarily raising two of the least popular taxes: sales and property. (City Council hearings will determine the final shape of Nutter’s budget.)

Perhaps the most intriguing results were those that suggested a gap between conventional political wisdom and real citizen concerns. Most notably, participants showed considerable openness to the idea of closing a prison and/or reducing the inmate population as a cost-saving measure. This in a city sometimes derided as “Killadelphia,” where the sitting mayor campaigned on a promise to introduce stop-and-frisk tactics to street-level police work.

Moreover, the discussion prompted by this potential measure—at least in one breakout group—was exactly what most public debates are not: enlightening. While five or six people approached agreement that some nonviolent offenders might merit clemency, a broad-shouldered man who had been listening attentively raised his hand. Sitting among the desks of a first-grade classroom, he looked like a quiet giant. “I’m a felon,” he began. “I’ve been out for 22 years, but I served all my sentence. And I guess I’m not sure how I feel about letting people out before they’ve paid their debt.”

Another man raised his hand. “I’m an ex-con, too,” he said. “But I’m trying to be a productive citizen now. The thing about prisons here, though, is that most of the people in them haven’t even been sentenced yet. You could wait six months in there before you even go to court! And it costs a lot of money to keep folks in there. Something like $38,000 a year. If we could figure out how to avoid that, we’d save more than you can imagine.”

As it happened, the deputy mayor in charge of prison issues had just taken a seat near the group’s circle of chairs. In response to a question, he confirmed that this was indeed the case.

The second man continued. “So I think there’s room to decrease the inmate population as long as it’s nonviolent offenders, but you’ve got to keep the job-training and re-entry services. Without those, I don’t know where I’d be now.”

The first ex-con nodded in agreement. After another couple minutes of discussion, the group altered its original decision: it would recommend reducing the prison population by 1,200, but retaining the re-entry services some had been ready to axe a moment before.

If nothing else, the Penn Project for Civic Engagement had actually produced a kind of civic engagement that many participants had likely considered extinct.

Just how much the “Tight Times, Tough Choices” project will impact the city’s budget remains to be seen, but for Sokoloff, exchanges like these are the whole point.

“I think there are certain muscles of citizenship that people need to develop, and work on, and strengthen. And the ability to come together and deliberate rather than debate is a key muscle,” he says. “Individual opinion is not public judgment. What we’re trying to do is figure out models and mechanisms to bring people together so that they can begin to think about what it means to have a public judgment, to define together what the public interest is. And we’re getting closer.”

—T.P.

*Note:

The original version of this story mistakenly referred to five buckets. There were four.