Two filmmakers went on the road with a family-owned circus and found enough human drama outside the ring to rival the snarling tigers, horse-riding bears, and aerial acrobatics within.

By Robin Rosenthal | Illustration by Josef Gast

APRIL 3, WEBB CITY, MO.

Tarzan’s not at the truck lot.

“Try the animal barn,” the secretaries say.

“He just called from over there.”

Down the road we go in our rented van, back the way

we came from our motel. A couple of horses graze in a pasture. Two kids

outside a trailer stretch like kittens.

“Should we shoot?” we ask each other. “Better

not till Tarzan knows we’re here.”

In the barn, seven elephants bob and sway, anxious for

their feed. The groom commands the elephants to hold their trunks high

up in the air, waiting until each one has its tub of grain before eating.

Afraid we’ll miss something we’ll kick ourselves for later, we shoot in

the dim light. But Tarzan’s not there either. “Try the truck yard,”

we’re told.

Back we go. Webb City is starting to look awfully familiar.

The back corner of the lot is occupied by a dozen semis in various stages

of loading and unloading. Guys stand around drinking coffee, giddily insulting

each other. Glittering circus-ring curb is hauled out of one truck and

into another. Racks of heavy stage lights are wheeled in.

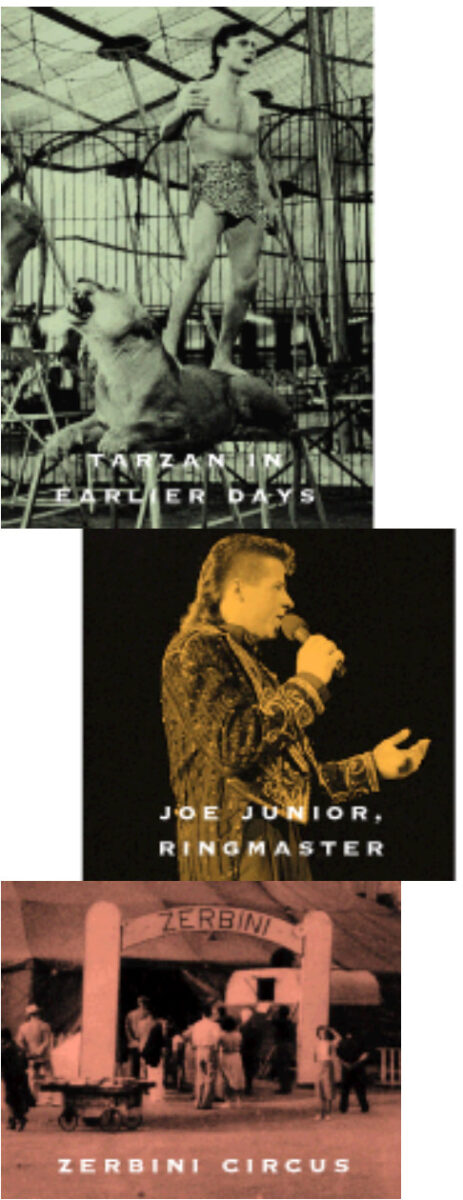

A burly man in a denim farmer’s jacket barks out orders

as the daylight begins to fade. This is Tarzan. We propel ourselves into

his world, shift our gear to one side and stick out our hands. “Hi,

we’re Robin and Bill, the documentary filmmakers.” He directs a shrill

whistle to someone else. “Careful with those lights,” he hollers.

Hardly a nod in our direction. “Guess we’ll just start,” we

say. “Okay?” Is that a grunt we hear? We look at each other,

shrug and begin shooting in earnest.

The next day, April 4, we wait hours for a long shot

of the whole caravan leaving its winter quarters. Tires are repaired.

The fuel man comes. The families’ motor coaches gather. Tie-down straps

and chains are checked and re-checked. Finally a toot signals that the

procession has begun. In majestic slow motion, their giant grills gleaming,

the trucks come at us, one after another. It’s a gorgeous shot, exactly

what we hoped for. The steel truck. The tent truck. The prop truck. We

are just learning what all this means. The people we have just begun to

know honk and wave from their cabs.

We’re off and running, about to hit the road with the

Tarzan Zerbini International Circus.

EARLIER, LOS ANGELES

Bill Yahraus C’65 ASC’67 and I met in Hollywood working on a movie called Lush Life, produced by another Penn alumnus, Jonathan Sanger C’65 ASC’67. Bill had been primarily a feature-film editor (Heartland, Country, Far North, The Long Walk Home, Silent Tongue). Years before he’d made documentaries, coming out of the documentary unit at KQED-TV in San Francisco in the late sixties. In Los Angeles he’d founded a co-op called Focal Point Films, where he made the award-winning film Homeboys, about an L.A. gang. I was toiling away as an assistant editor in movies and TV. My major at Penn had been fine arts, and I had an MFA from Queens College. I had taught college-level studio art in San Antonio for several years, exhibited some work as a video artist and done some fiction writing. Neither of us felt creatively fulfilled in our Hollywood world. Nothing so unusual, really.

We did a few jobs together, and I became an editor. Somewhere along the way we became a couple. We decided to make a documentary together. Bill had always been interested in circus, in the real lives behind the dazzling artistry and showmanship of the big top. I was drawn to the cheap thrills of the carnival midway, to the itinerant life of its performers and the garish visuals of the rides, games and grab stands. We started out by ignorantly lumping these two folkloric subjects together — circus and carnival. Our first stop was Gibsonton, Fla., the winter- and retirement-home of many carnival performers. “Gibtown” was a fascinating place. In the morning we’d tape in the trailer home of octogenarian Melvin the Human Blockhead as he pounded ten-penny spikes up his nose, or ran through his old contortionist’s routine. In the afternoon we’d sprawl on the carpet at Giant’s Camp with “half-woman” Jeannie Tomeini, flipping through fabulous photographs from the old freakshow days.

We talked our way onto the grounds of the Florida State Fair as the midway was being constructed, and there we had our first encounter with the Tarzan Zerbini Circus. Tarzan himself reminded us of the teamsters we knew from the movie business: huge, gruff, a little scary. Climbing into his Rolls, headed back to Missouri, he told us we couldn’t talk to anyone but his daughter. We obeyed — for a while. Then Joe Bauer took over. We assumed that Joe, the agent for the circus, co-owned the show. Joe opened the door wider. One peek at this ninth-generation, family-owned circus, and we were hooked. With a Hi-8 camera, the tape stock was cheap. We continued to explore and shoot. Back home, we tried to combine our interest in both circus and carnival, shopping around a proposal called Barnum & Bailey’s Daughters. A year passed, and no funders bit.

Perhaps concentrating on just one of the two subjects might attract funding, we thought, so we asked Joe Bauer about going on the road with the Tarzan Zerbini Circus. It was March. He said they were leaving in April, and yes, we could come along. Based on his permission, we looked for funding, again unsuccessfully. We decided we’d better just go, and hope the money would follow.

But something told us to make sure we also had Tarzan’s approval. You don’t just follow people around for a month without an understanding. Joe Bauer said he would speak to Tarzan on our behalf. The deadline to pay for our plane tickets approached. The rental camera was on hold. We still had heard nothing. Finally, we called Tarzan directly. “We just want to be sure Joe told you we’re coming along,” we said. “It’s my circus,” Tarzan said. “Who the hell are you?” Shaken, we laid out our idea. “I’ve got a truck running outside,” said Tarzan. “Talk to Joe.” We packed our bags.

APRIL 5, MANHATTAN, KAN.

A small herd of age-college boys mills around waiting to work. The big red and yellow tent has returned from repairs in Italy in sections, so it must be laced together from scratch. But there’s no tent boss yet to organize the workers. It’s going to be tough to set up in time for the first show.

We lurch around with our gear, attached to each other by cables, our footwork unpracticed. Bill does camera. I do sound. Everyone thinks we’re The News. Through my headphones I hear the relentless jackhammering of the tent stakes, and “What Channel? What Channel are you from?”

We soon see we could make a film just about Setup.

Tarzan does a kind of ballet with his trucks, motioning them into precise

positions on the empty field — his stage. The stakes go in, the towers

go up, the canvas rises, the tent poles are shoved into place. It’s timeless

— the circus comes to town. Everybody’s in a great mood in spite of the

pressure of showtime. They love this beautiful tent. Joe Bauer adopts

the role of tour guide, bragging in his heavy Swiss-German accent, “A

tent to make is like a good suit, and the best cutting is in Italy.”

He says he will call a meeting to introduce us and explain what we are

doing. This never happens. Therefore, everybody thinks we want a soundbite.

They don’t understand that we’re going to be with them for a solid month.

People rush into their trailers, emerging with fistfuls of photos they

thrust at the lens, as if the showbiz version of themselves in the photograph

is more real than the person standing in front of us.

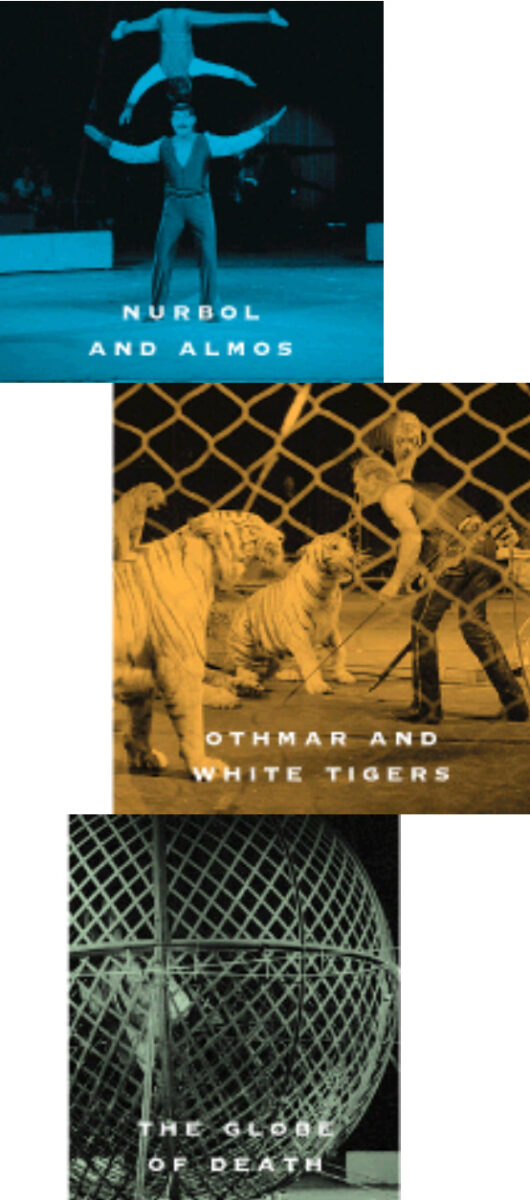

Another Swiss-German, tiger trainer Othmar Vohringer,

is wrestling cages of Siberian white tigers out of their truck. Down the

truck ramp, his young groom, Mike, is startled when the winch cable lets

out suddenly and one of the heavy cages lurches toward him. Othmar insists

there’s nothing wrong with the “vinch.” There’s loads of bumping

and snarling and cursing. But charismatic Othmar is thoroughly relaxed

in front of the camera. Later, sharpening his knives over a table crammed

with rooster saddles and bloody, charcoal-blackened beef, Othmar tells

us that before he could join the circus, his father said he had to learn

the family business — butchering. While he cuts the tigers’ meat, we

get a great long interview, just the way we like it — somebody actually

doing something instead of posing stiffly for the camera. Bill has forgotten

his lens tissues in the van, and the sun is pointing into the lens, aggravating

the dirt spots, but we’re too excited to stop. Bill keeps wiping the lens

with his shirt sleeve. We may have found one of our main characters already.

Our intention is to make a cinèma-vèrité-style documentary in which we’ll capture the feeling of life on the road with this contemporary traveling tent circus. We want an intimate look at the members of this community, and hope that over time the personal stories of a handful of major characters will emerge. We plan to be on the lot from morning until night in every town on this Midwestern leg of the tour, right up until they cross into Canada. After exploring the idea of renting a mini motor home so we could stay on the lot, we have opted for motels to be certain we’ll have electricity when we need it for our equipment. Also, we think we may occasionally need to put some distance between ourselves and our subjects.

We quickly fall in love with everyone — the hot dog guy, the drivers, the grooms, the tent crew, the performers, and the ruling families, the Zerbinis and the Bauers. If they’re willing to let us follow them around, we’re willing to shoot.

Othmar spends countless hours talking to us about animal training, animal-rights issues, history and politics, and lets us tape several instructive practice sessions. Bauer scion Joe Jr., the Ringmaster, always knows where the camera is. Billy and Mark, the motorcycle daredevils, open their trailer and their lives to us unconditionally.

We also get to know three families of Russian performers who are on the tour this season. A father and son from Kazakstan, acrobats Nurbol and Almas, perform both a hand-balancing act and a pole routine. Luba Tchepiakova and her husband, Kim, carry on her family’s circus-act tradition, in which Siberian brown bears ride Russian draft horses. The Karimas have three acts: Pavel and his partner, Vassili, do an awesome hand-balancing routine “at the apex of the big top.” Pavel’s wife Natalia, disguised as a limp rag doll, pops out of a samovar and is spun and twisted into impossible positions in their traditional Russian Doll act. Teenage daughter Olga, the family’s translator, has a solo aerial act.

The only performer we have trouble getting near is Tarzan’s flame-haired daughter, Patricia Zerbini. Before we met her, Patty was described to us as the son Tarzan never had. Not only is she a well-respected big-cat and elephant trainer, but she can drive a semi, weld, do basic truck repair and execute a neat split between the heads of two lumbering beasts. She is raising her two boys alone after the death of her husband in a Ringling train derailment just a couple of years earlier. She has an edge you could cut meat with. When I point my microphone down into a first-day conversation between her and Othmar, I’m on the receiving end of a snarl scarier than the tigers’. In the first couple of towns she ropes off the outer perimeters of the elephants’ area, and then stays inside so we can’t get near her. We don’t want to piss her off because we know that one complaint to Daddy and we’re history. So we respect her boundaries and resign ourselves to the idea that she might not feature much in the documentary.

What a shame. Her elephant act is awesome. No matter how many times we shoot it, we still get chills when the elephants thunder by, so close we can feel the wind off their backs, their thuds shaking our tripod, Patty running around inside their circle Balanchine-style. But if we don’t have a character, the act won’t mean as much.

APRIL 30, ROCKFORD, ILL.

It’s our last day on what we think is our only shoot. We’ve seen Othmar’s groom lose a bit of finger to a tiger. We’ve ridden along with Tarzan in the steel truck, piled high with the underpinnings for the seats and bleachers, hearing about the comedy lion-and-tiger act he’s famous for, and about the time he needed 500 stitches. We’ve watched Olga slip from the rings. We’ve shot in the rain. We’ve crippled our camera shooting through a horrendous dust storm in Hayes, Kan. Now it’s snowing.

We have emerged from a foraging expedition to the local Wal-Mart wearing twin blue-and-orange “Fighting Illini” caps, the only cold-weather gear we could find among the spring merchandise. The circus crew and performers who now feel intimate enough to poke fun, nickname us “The Smurfs.” We’re wearing these hats, and Patricia Zerbini has finally consented to be interviewed. She has seen us interviewing other performers and now, we figure, she realizes they could steal the show.

The problem is, the camera doesn’t work anymore. We’ve been in and out of local cable stations, cajoling kind engineers to clean its heads. But now it’s beyond head cleaning. Too much wind. Too much dirt. We think the audio might still be good.

So we decide to go for it, thinking maybe we can use Patty’s audio with other images we’ve got of her. First she insists on the elephant tent, where it’s too dark and the heat blower is making far too much noise to get clean sound. That’s okay, it turns out. Here she gives us the top layer only, the rote stuff she’d say to any local-newspaper guy. We suggest going inside her motor coach. It’s warm and surprisingly girl-like in there. Patty thaws. She gives us a few real glimpses of herself, which, of course, with the broken camera, we are not really getting. We could kill ourselves for having shot in that dust storm.

LATE SPRING LOS ANGELES

Back home, having dubbed and logged what we’ve got

so far, we see we have no movie. We think the documentary should take

a chronological shape, but with the fiasco of the broken camera, we really

have no ending. There are gaps in our performance coverage and characters

to flesh out. Do we quit now, or do we shoot more? Money, we don’t have.

Lots of footage, and a great beginning, we do have. We decide to go for

the whole enchilada.

JUNE 24, SCARBOROUGH, ONTARIO

After getting our gear through Canadian customs, we find the town, a Toronto suburb, and the mall parking lot where the circus is setting up. Patty Zerbini gives us a surprisingly warm greeting, and we know we will get what we need now.

Much has changed. The circus is running like a well-oiled machine. Energetic new drivers and tent crew have come on board, as they do every summer in Canada. The weather is glorious, and the guys are all showing off their tanned, tightened selves. Everyone is happy to see us.

Good ol’ Texas boy Billy Rogers, who rides a motorcycle around inside a 12-foot diameter metal globe, is hanging out with Russian aerialist Olga Karima. Billy’s partner, Mark, has something going with a red-haired concessions girl. Othmar’s tiger groom, Mike, has been joined on the tour by his best friend from back home, Sue Bird. Sue has been hired to provide schooling for some of the children traveling with the circus, and after class she sits on her bunkhouse stoop and breathlessly fills us in: She’s always wanted to travel, she’s quit her nursing job, she and Mike are not really together “like that,” and by the way, they’re pregnant. “Oh boy,” we say, mimicking Othmar’s habitual response. We hope we can find a way to include this news that isn’t exploitative.

Sometimes we hang out with our new friends at the end of the day, and by now, we are so fond of our subjects that the line between friendship and filmmaking is blurring. It’s the documentary maker’s dilemma — to sort out what helps tell the story, and what is needlessly invasive. They will become “characters,” versions of themselves useful for telling our story — and theirs — the story of a season on the road with the circus. But of course each of their stories is much more complicated than their “characters,” deeper than we can possibly reveal.

OCTOBER 12, CHATTANOOGA, TENN.

We’ve just driven up from Montgomery, Ala., where half the circus is playing a state fair; the others are here in Chattanooga. The circus has crisscrossed Canada from Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia, gone all the way back west to Willmar, Minn., and then come south. Soon they will head home for one final date in Carthage, Mo. The Chattanooga venue is a vast, gymnasium-like space, with horrible fluorescent lighting. Our inside footage looks awful. But the story waits outside.

Motorcyclist Billy Rogers, whom we have come to think of as our very own Patrick Swayze, backlit by the intense southern sun, spins out his tale of woe. His partner has run off with that girl from Canada, leaving him in the lurch. No motorhome, no Globe of Death, no motorcycles, no act, no paycheck. Even worse, Billy had leased this equipment from a cousin of Tarzan’s, and had agreed to be responsible for it. As a substitute, he has summoned his sister from Wichita Falls, and together they have resurrected a shaky aerial act. Meanwhile, Othmar has fired his tiger groom, the father-to-be. Pregnant Sue is also gone. The Karimas are tense over Olga’s future with Billy. We follow our characters around, struggling with the feeling that we are shameless bloodhounds. We plan to sort out later what feels fair and honest and what feels cheap. But now we have to gather everything we can to make the personal come alive.

Tarzan heads back to Montgomery — where the tent is — to help Joe Bauer with the Teardown. We follow. The fairground is almost empty but for spotty piles of trash. “Look at this.” Joe Bauer gestures around at the desolate scene. “So sad.” He finds three little pots of wilted pansies. “For my wife. What do you think?”

They clown for us. Joe tries out some handstands on the moving forklift, his performing days long past. Still the comedian, Tarzan hops out of the driver’s seat of a moving truck and motions for it to follow him.

Joe goes into one of his retirement riffs. “I think I’m gonna retire,” he sighs. “There are so many beautiful things to see. The sad thing is we don’t take the time. Zurich. How many times I played there. Basel. Stuttgart. Munich. I was all over the world, and what did I see? Nothing but a circus and a building or a tent.”

The melancholy of their lives comes home to us. This world, so free of earthly constraints in the ring, so full of daring, of adventure and romance, is nonetheless in its own way both circumscribed and routine. Rarely did we see anyone go off to explore any place further than the mall or perhaps a nearby casino boat. They really can’t. There’s no time. There are animals to look after. Riggings to repair. New tricks to practice. And always the next town to get to. The edges of the lot are the boundaries of their world. The only thing that takes them outside is the road itself. And it’s always beckoning, but only as far as the next town.

Joe Bauer Jr. told us about the time the family actually had decided to sit out a season. They would stay home in Sarasota, going to school, swimming in the pool, doing what other people did. After a couple of months they were going nuts. Joe Sr. booked out the family’s act, The Fearless Bauers, and soon they were on the road again. We don’t believe Joe will be retiring any time soon.

That night, we take Joe and Tarzan out to the local steakhouse for a thank-you dinner. In the morning we will follow Tarzan’s caravan on the 1200-mile trip from Montgomery to southwestern Missouri.

OCTOBER 19, CARTHAGE, MO.

Carthage is next door to Webb City, the circus’s winter quarters. For the first time, the circus will run as part of the town’s Maple Leaf Festival. But except for the fun of participating in the parade, the general energy level here is noticeably down. Everyone seems tired and ready to go home, wherever home is. We begin to feel it too, as if we have become a part of our subject. The maple leaves are blood red against the brooding skies. Maybe we have stayed too long at the fair. We wander around wondering what else to shoot.

Once in a while we are privy to little explosions of emotion. The Zerbini cousins who own the missing Globe of Death have arrived on the scene, and are arguing loudly with Billy over how to handle the situation. We see that Billy is really worn down raw and is seriously considering leaving the business he was born into. Embarrassed, we hang back a little as he and his sister have a heart-to-heart. When her parents are away, Olga invites us into her trailer and proceeds to unload the season’s baggage. Her story is one of an overwrought 19-year-old girl, swamped by first love, class politics, homesickness and the cruel world. We know as we are shooting that she is far too vulnerable and that we will protect her in the editing process.

While painting gold tips on her fingernails, our new best friend, Patty, tosses us a wonderful ending for her story line. There’s a sweet interchange between Othmar and his new tiger groom, a farm girl from North Dakota. After the last show, we shoot one long continuous scene of Tarzan and his crew rolling up the final section of tent canvas for the season. Tarzan is barking and cursing just like the first day. Miraculously, the whole shot makes it in one piece onto the short end of a tape. That will become the end of our movie. The season is over.

With Oregon Public Broadcasting as their presenting station, Robin Rosenthal C’76 and Bill Yahraus C’65 ASC’67 received finishing funds for their documentary from PBS. A Circus Season: Travels With Tarzan will air on PBS stations nationwide on July 21. They can be contacted by e-mail at Robinmrose@aol.com and Byahraus@aol.com