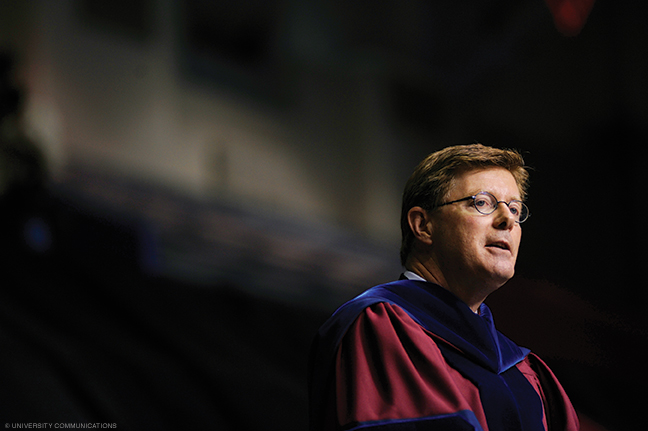

“Bittersweet is the only way to describe this moment,” Vincent Price said. Penn’s provost, who steps down at the end of next month to become president of Duke University, called his 19 years as a Penn faculty member and administrator “without exception the best years of my professional life.”

He stressed, more than once, the importance of the relationships he’s developed. “The largest impact that I probably will have on the institution rests in the people I’ve worked with, the leaders around the campus that I’ve had a hand in appointing,” he added. “And it makes me feel terrific—and deeply grateful.”

President Amy Gutmann, who also used the word bittersweet to describe his departure, noted that since becoming provost in 2009, “Vince has brought extraordinary leadership and vision—as well as grace and good humor—to our academic enterprise,” adding: “No one is better prepared or more deserving than Vince to lead a distinguished university such as Duke.”

A scholar of political communication who came to Penn via the University of Michigan, Price (now the Steven H. Chaffee Professor of Communicationa and Political Science) joined the Annenberg School faculty in 1998. In 2007 he became associate provost for faculty affairs, and two years later moved into the provost’s office.

Price spoke with senior editor Samuel Hughes in late March.

Talk about your first impressions of Penn, and the changes you’ve witnessed.

The first time I interviewed at Penn in the early 1990s, there was still a parking lot where the Inn at Penn sits today. So when I talk to students about the Penn campus and their sense of how seamlessly it flows into the University City community, we have to stop to remind ourselves of what a boundary Walnut Street at one point represented. That transformation was already underway when I arrived, but it has come to full fruition.

I’ve seen a number of critical changes. One, physical transformation of the campus: the addition of Penn Park and so many new academic buildings, including the Annenberg Public Policy Center.

That physical transformation has been coupled with a transformation in the capacity of our faculty and our student body. This university represents the finest students in the world, the finest faculty members in the world. Again, this trajectory was established well before I arrived. But it is striking to see, with each successive hire, how much more impressive we become, collectively speaking. The faculties have not grown all that much. But they have deepened and strengthened in immeasurable ways.

The third thing, and this is less a change in the campus than a change in my perspective, given my roles, is just how astounding the people here are—as researchers, as students, and as academic leaders. I don’t think you can find a better leadership team on a campus anywhere.

What are some of the biggest challenges facing Penn?

The challenges that Penn faces are not unique to Penn. They affect most of higher education today. They also represent opportunities. The first is technological in nature. If one looks at the way that technologies that were unleashed in the postwar period accelerated through the ’60s and ’70s, they have transformed so many industries and so many markets and changed the way we live—walking around now with mobile devices that didn’t even exist 15 years ago.

The strength of universities is their ability to maintain practices that have shown their value over centuries. So they are conservative institutions in the sense that they preserve the best of human culture and work ways. They have been relatively little transformed to date by those technologies in their educational work and their research. But they are being transformed. And that should be an active transformation, thoughtfully navigated by faculty and leaders of higher education, rather than things that creep up on these institutions as they have on other industries.

Are you talking about Coursera and MOOCs and that sort of thing?

Absolutely. And I’m proud of the way Penn has responded. We have been very thoughtfully engaged in those activities. We haven’t moved quickly to those areas that are core to the educational mission. We start with executive training programs and massive open online courses. But we are taking that experience and pulling it back into the core enterprise.

This winter we opened a new facility in the first floor of Van Pelt. And the Center for Teaching and Learning—the online learning initiatives program of this office—and a new Center for Learning Analytics are now located there. We’re launching new masters-level programs that are hybridized, that have an online as well as a face-to-face component. So there’s been a kind of quiet transformation of the way we do our work. And it’s absolutely necessary.

Another major change really has been the globalization of our enterprise. Our first student from China came to Penn 100 years ago. But navigating what it means to be a global university is not a straightforward proposition. Other institutions have tried to build out a physical network of foreign campuses. That was not something that Penn took to. But we are in a virtual way, without question, far more global today than we’ve ever been in our history. And we do have some important initiatives. The Perry World House has just been launched to navigate those opportunities and marshal the strengths of the entire faculty and student body around present global problems. The creation of the Penn Wharton China Center is another example. The creation of a Vice Provost for Global Initiatives here to coordinate those activities, and the work that Zeke Emanuel has done in that role.

The third set of opportunities and challenges concern the ways that American higher education has funded its work—largely through public funding in the case of our public universities, research programs, federal research dollars. These things are all under tremendous stress. That delicate web of cross-subsidies that created a thing of enormous power and value—that return demonstrable economic dividends to the country, and which benefitted generations of students—is under some threat.

There’s a very short-term mentality that drives a lot of decision-making right now. And that is of great concern. So recovering some of that educational infrastructure is a responsibility of institutions of higher learning, partnering with political leaders and members of the community.

Some of that we see already developing, such as the kinds of commercial partnerships that we’ve been developing through the Penn Center for Innovation. The shift in our sponsored research portfolio—not away from federally sponsored research, which is still the lion’s share of that portfolio—to a tremendous growth in industry-sponsored research. These things don’t happen by accident. They are strategic moves.

We’re also part of an important project to open up access to higher education as one of the cornerstones of President Gutmann’s compact. That returns enormous value to society. There are very few institutions in contemporary society that have that wherewithal. The project of creating a more diverse, open society doesn’t begin with higher education, but it will fail without a vibrant activity in higher education to advance those goals.

Are you concerned about the more nationalistic, border-protecting approach to the world within the United States, which would affect the students and faculty that Penn brings in from abroad?

I understand the concerns that have been generated by the impact of globalization. Moving forward in a way that addresses all of those concerns without turning back the hands of the clock is the primary challenge. Institutions of higher learning are a part of that move toward globalization in a positive sense. We depend upon a lot of flows of students and faculty members across borders. A restriction in those flows will have adverse consequences for the work that we do.

That being said, I think we need to take seriously the concerns that are represented by the public support for that turn. But it would be to our great loss as a nation, as well as a globe, if we turned to a much more isolationist view of the world precisely at the moment when the technological drivers and the economic drivers suggest that broader transnational cooperation is, in the long run, the best way forward.

Are universities under siege as custodians of knowledge?

Universities occupy a critical place in our societies—a place of enormous productive creative tension. We’re the place where the wisdom and experience of age run up against the enthusiasm and ambition of youth. We’re the place where we are custodians of the past, the deep past. We have the Penn Museum of Archeology and Anthropology here on campus.

I understand the sort of narrowing of vision right now, the sense that we want to see a fairly rapid return on that investment. But things that may seem to the outside world as aimless and not particularly productive have time and time again demonstrated their power after decades—sometimes centuries.

And that does feel a bit under threat at the moment. It requires some broad education to explain the value proposition in doing that. This is not really just about the humanities, although they are under attack. There are basic scientists very concerned that the drive toward translational science and short-term demonstrable impact of that scientific work puts at risk basic scientific work, the value of which may not become clear for decades. We have a responsibility to foster that.

I think the most thoughtful people recognize this. It’s not always clearly communicated. And at times where there are so many pressing demands on particularly public resources, it is harder to make that argument. But that is precisely when the argument has to be made, and made with vigor.

As provost, you have to wield this synergy of academic talent, money, and administrative savvy. And there’s got to be some sort of academic politics involved. What advice would you have for the next provost?

My advice to my successor would be savor every minute of it. It’s been an honor to serve as the provost of an institution like Penn; to work with, as I said, the kinds of faculty members and leaders we have here; to work with student leaders. We have a Student Committee on Undergraduate Education. I meet with them on a regular basis. They are an absolute delight. They’re thinking deeply from the perspective of the student about what it means to be at Penn, and how they can make the educational experience better for generations following them.

It does have its administrivia. But I find those moments anything but tedious. Because the devil, as they say, is always in the details. I have no problem with details, and with the kinds of leaders we have on the campus, I don’t think that my successor will find this a challenge. It’s a large and complicated place, and it gets a little rough-and-tumble at times. But everyone here works with a common spirit and purpose, and so long as we create opportunities for the right conversations, people can and will agree to disagree, and move on.

Now, that being said, it is political. Because of our openness and our willingness to live that rough-and-tumble lifestyle, it’s a place where viewpoints love to land and express themselves, oftentimes right out here by The Button. And that brings challenges. It’s difficult to open the newspaper today and not read of something happening on some other college campus. But what I so admire about Penn is the culture it has developed of being willing to engage in serious conversations about what’s at stake.